Obesity: Selling smaller food portions could solve crisis, say scientists

Report calls for Government to limit sale of 'supersized' food and drink items

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Radical changes to the way food is served and sold in Britain in order to encourage smaller portion sizes will be needed to tackle the growing obesity crisis, senior nutritionists have warned.

Smaller servings in restaurants, take-aways and canteens, as well as smaller plates, cups and glasses and even smaller cutlery that hold daintier mouthfuls, can all help to prevent overeating, the scientists said.

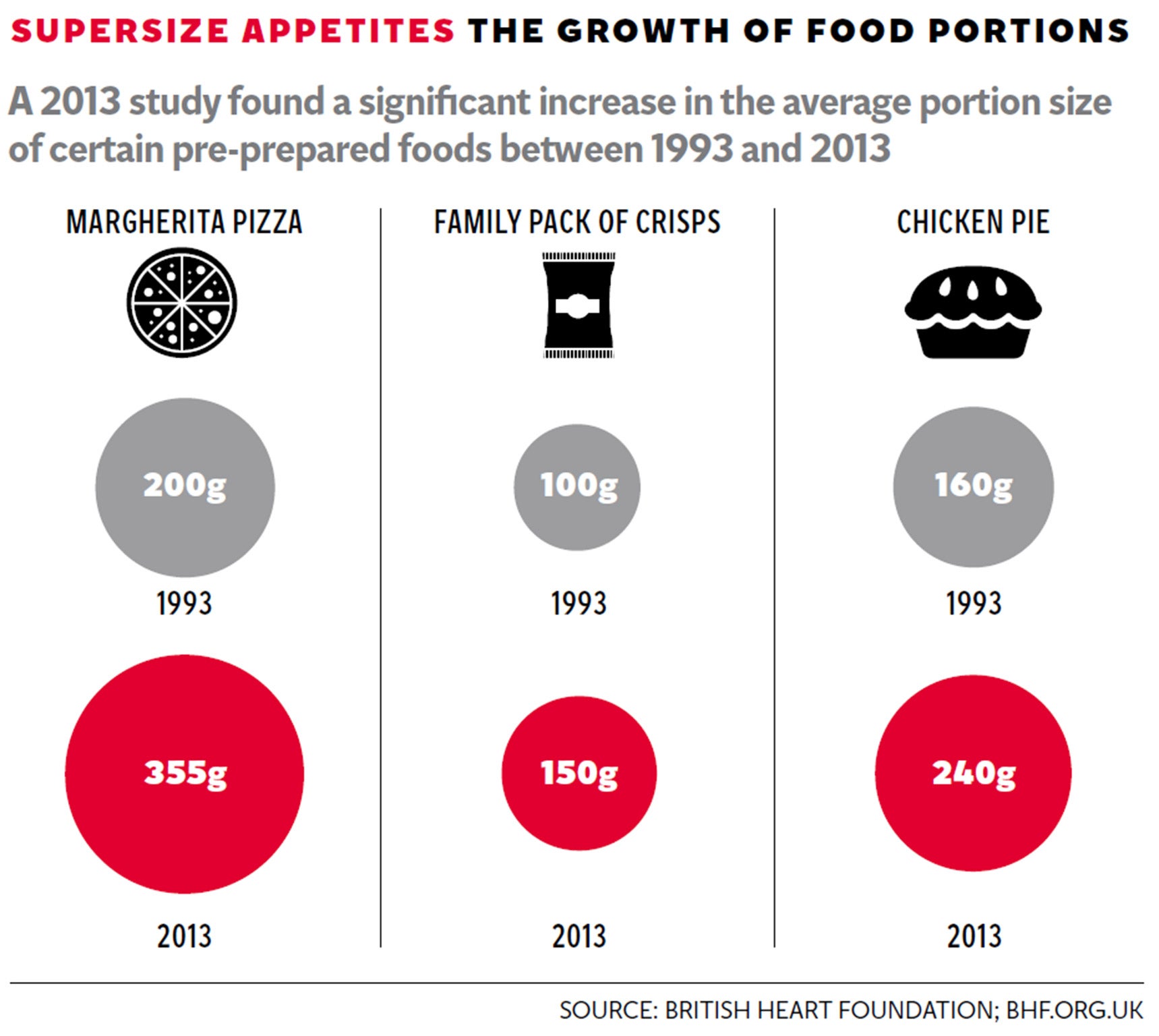

Packaging sizes also need to be made smaller, with an end to price reductions on larger food and drink products. Typical food portions should revert to those commonly seen in the 1950s, before the era of “supersizing”, they said.

Studies have consistently shown that people consume significantly less food and drink when served smaller portions. The trend towards larger portions is considered to be a major factor in the obesity epidemic.

“The 1950s were healthier in part due to smaller food portions, packages and tableware prevalent at the time,” said Theresa Marteau, professor of behaviour and health at Cambridge University, who led the study.

The average size of portions, packages and tableware has increased significantly over the past 50 years, while the proportion of people diagnosed as overweight or obese has mushroomed, the scientists said.

Measures designed to eliminate larger portion sizes from the diet could reduce the average adult’s daily energy intake through food by between 12 and 16 per cent in Britain, according to the study, published in the British Medical Journal.

“We now have compelling evidence that people consistently eat and drink more, often without awareness, when offered larger sizes portions or packages or using larger items of tableware,” Professor Marteau said.

“The size of the effect suggests that eliminating larger-sized portions from the diet completely could reduce energy intake by up to 16 per cent in UK. Informing people about this effect has little or no impact hence the need for policy options that reduce the size, availability and appeal of large portions, packages and tableware,” she said.

A recent study found “the most conclusive evidence to date” that people consume more food or drinks when served or sold in larger sized portions or packets, and yet there is a commercial drive to make portions bigger in order to sell more.

Voluntary controls or guidelines in the food industry are unlikely to work because the companies who move first are likely to be a competitive disadvantage, which means that regulation would be needed, the scientists said.

“We think that the food industry may find it difficult to act without regulation given ‘first mover disadvantage’,” Professor Marteau said.

Making food servings smaller and using smaller tableware and cutlery, with shallower plates and straight-sided glassware, can all help to restrict over-consumption, the scientists suggested.

“Public acceptability is key for government action. The public are more accepting of government intervention to protect children – which includes preventing obesity,” Professor Marteau said.

“The public is also more accepting of government intervention when they are given information about their effectiveness, and when they see the environment, and not lack of willpower, is a key driver of over consumption,” she said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments