New alcohol guidelines: How is drinking linked to cancer?

The new drinking guidelines include recommendations to cut the risk of cancer. Sarah Williams of Cancer Research UK explores the link

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.After much media build-up, Professor Dame Sally Davies, the Government’s Chief Medical Officer, has announced updated guidelines on low-risk drinking for the UK.

Today’s announcement has been in the pipeline since the previous government announced in 2012 it intended to have them reviewed. And over the last year there’s been growing speculation as to just what the new guidelines might look like.

This update is welcome – the guidelines were last reviewed back in 1995 – and thorough, drawing on three different expert groups and multiple reviews of a wide-range of evidence. It aims to prevent a broad range of diseases, as well as injuries and accidents. But it’s also influenced by the considerable evidence that has emerged showing that even low level drinking can increase the risk of some cancers, and that this risk increases the more alcohol people drink.

The changes are also down to a weakening of the evidence that there are health benefits to drinking alcohol – so the new version is about minimising harms, rather than considering them in addition to benefits.

So what’s changed? What do the new recommendations mean for you? And how has the evidence changed since the last update? We’ll discuss this below. But first, one thing that hasn’t changed is that the guideline amount is measured in ‘units’ of alcohol. And you aren’t alone in wondering…

What is a unit?

One unit is defined as 10ml (or 8g) of pure alcohol. But that probably hasn’t helped you know how many you’re drinking.

The difficulty with communicating about alcohol consumption is that it’s very difficult for people to measure and track what they’re drinking. Chiefly this is because people (thankfully) don’t drink pure alcohol, and different drinks contain different concentrations of alcohol (hence ‘ABV – alcohol by volume – the % figure on many drinks which is the proportion of pure alcohol it contains).

And that’s before you factor in pub measures versus what people might pour themselves at home.

So using units is a way of trying to standardise advice on alcohol. But it’s far from ideal, and there’s lots of evidence (e.g. this study) that people struggle to understand what units mean, and that they aren’t the same as ‘drinks’. The committee that drew up the guidelines was aware of these limitations, but despite searching for a different solution, they say “If there is a better alternative to the UK unit, we have yet to hear of it.”

As the graphic below shows, almost any drink you might order at the bar contains more than one unit:

What’s new? And what’s changed?

The main change is that the recommendation for men and women is now the same – to keep health risks to a minimum, people should drink no more than 14 units of alcohol a week. This is because the evidence now suggests men’s and women’s risks from drinking a given amount of alcohol are about the same – although men have a higher risk than women of immediate harms such as accidents and injuries, and women’s risk of long term illness (and premature death) is higher.

And the focus has switched back to weekly, rather than daily, limits. The previous (1995) guidelines introduced daily limits. And while these didn’t entirely replace the weekly recommendations, confusingly the two didn’t match up – people drinking up to the maximum every day would exceed the weekly limit by 7 units.

The daily limits have come in for other criticisms too – for example research published this summer, found that people who don’t drink every day (which is the majority of the population) tended to ignore the guidelines, because the advice didn’t seem relevant to them. The move away from daily limits has partly been motivated by research like this on how people understand and use guidelines.

And as we said above, the new guidelines also largely do away with the notion that alcohol is beneficial for our health.

The committee also wanted to help people reduce the risks from drinking large amounts on one occasion, and they’ve addressed this in a number of ways. Firstly, the weekly guidance also says if people drink as much as 14 units in a week, they should spread it out evenly over at least 3 days, cautioning that heavy drinking sessions increase the risk of accidents and injuries as well as long-term illnesses. As well as suggesting people limit the amount they drink in one session, there is also advice for people to help cut the immediate risks – such as drinking more slowly.

And it also suggests people have drink-free days to help cut down on the amount they drink.

The way the guidelines are now presented also makes it clear that 14 units per week is a limit, not a target. And they highlight that the risk for some diseases, such as mouth, throat and breast cancers, is increased at any level of regular drinking – so the guidelines don’t represent an absolutely safe amount to drink; they’re intended to keep a person’s health risks from alcohol to a minimum.

Finally, the committee has decided on a minimum risk level in context of other risks we expose ourselves to. So the 14 unit limit is the level of drinking that would be expected to lead to a lifetime risk of dying from an alcohol-related condition which is similar to the harms of other routine activities, such as driving a car (to be precise, about one per cent).

Cancer and the new guidelines

So that’s the new guidelines, and units, explained. But as we said above, one reason for these changes is the strengthening evidence of the link between alcohol and cancer. So what’s changed here?

We’ve blogged about alcohol and cancer many times – especially the link with breast cancer – but here’s a quick recap.

It’s been established for decades that alcohol can cause cancer, but the impact that lighter drinking has on risk has taken longer to tease apart. That’s because the effect on risk is smaller, more difficult for scientists to demonstrate conclusively, and also prove it’s not down to other things (such as smoking or poor diet) muddying the waters.

But more recently, it’s become clear that low level drinking (meaning around a drink a day on average) increases the risk of breast, mouth, throat and oesophageal cancers. And the more you drink, the higher the risk of these and other cancers. Altogether, alcohol is linked to seven types of cancer with bowel, liver and laryngeal cancers making up the total.

The extra risk for drinking at low levels is fairly small, so it probably won’t make much difference to an individual’s absolute risk of developing cancer – but over a population the size of the UK, where many people drink at low levels, it adds up to a big impact.

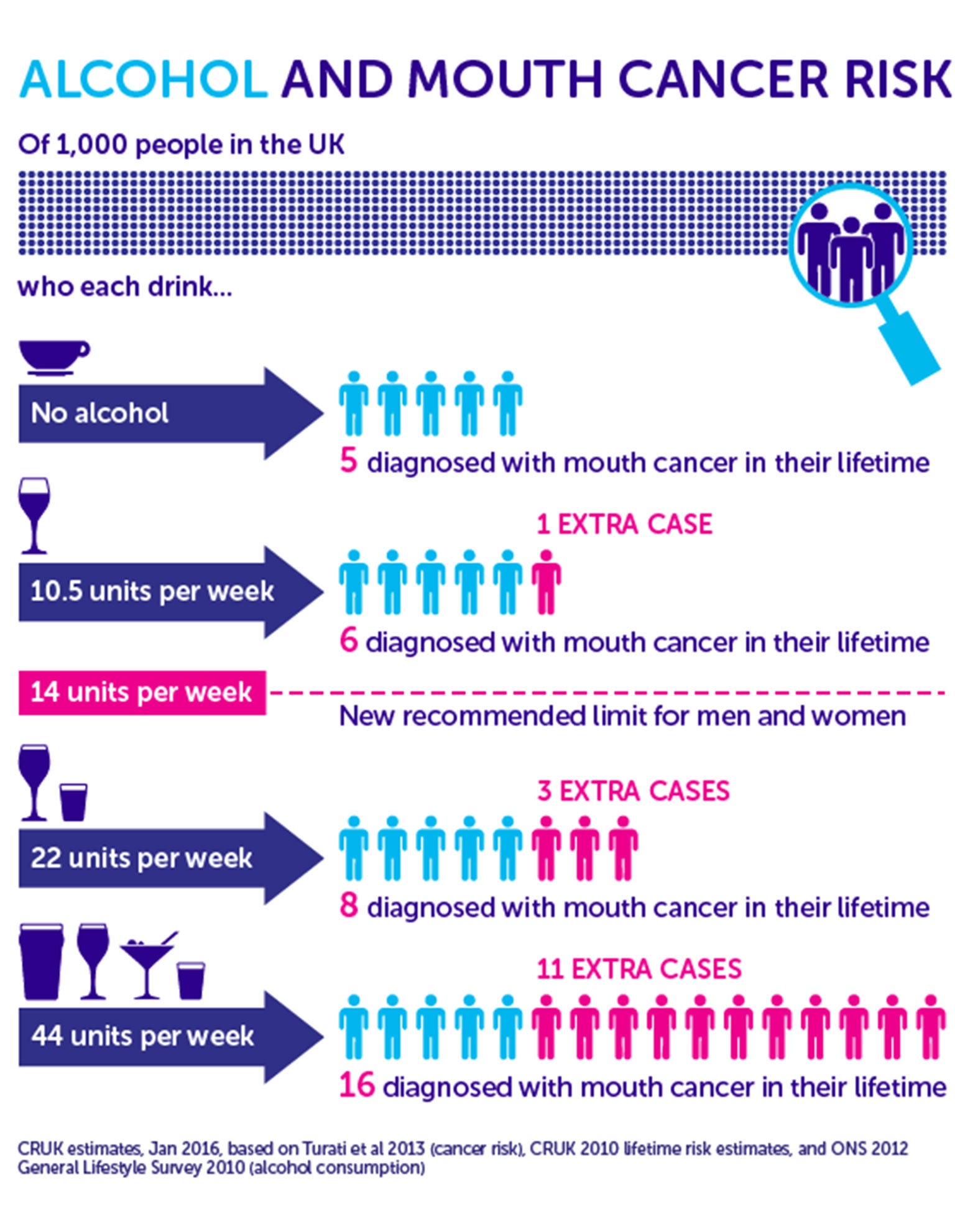

To try to show how even light drinking can increase the risk of cancer, and how the risk rises with heavier drinking, we’ve done some calculations using the latest evidence on how different levels of drinking affect the risk of mouth cancer:

These figures are worked out using the same method as we’ve previously used for breast cancer and alcohol drinking – but show the risk for mouth cancer which affects both men and women. There’s more detail about how we calculated them below*.

What can I do?

These guidelines are an important step in helping people understand – and reduce – the risks from drinking alcohol. When it comes to cancer, our advice hasn’t changed – the less alcohol you drink, the lower your risk.

There are lots of simple ways to start cutting down. For many people, simply tracking how much you drink can be an eye opener – there are lots of free apps and tools available, such as this one from Change4Life.

Some quick ways to cut out units are to choose lower strength beers and wines, opt for smaller servings – or you could try a shandy or spritzer. Or just replace every other alcoholic drink with a soft drink on a night out.

And if you’re drinking in a group, staying out of large rounds means you don’t have to match anyone else’s pace, and you can more easily avoid being cajoled into having a drink that you didn’t really want.

And there’s something else you can do too – the CMO has also announced a public consultation to check that the guidelines are clear, easy to understand and, perhaps most importantly, useful. And they’d like you to take part.

Everyone has their own priorities and their own approach to risk, but along with the CMO we believe people have a right to clear information to help them make decisions about their lives. We hope these new guidelines will help people understand and manage the risks of drinking alcohol.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments