Never before seen letters reveal the story of the scientist who laid the foundations of a cure for malaria more than a century ago

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When British doctor Sir Ronald Ross discovered the crucial link between mosquitos and malaria at the end of the 19 century, he understandably thought it marked the beginning of the end of the deadly disease – rampant then not only in colonial India and Africa, but also in southern European countries such as Greece and Italy.

More than a century after Ross’s momentous break through, malaria continues to kill hundreds of thousands of people every year- a neglected disease for much of the 20 century.

But, the laborious scientific hunt and subsequent elation felt by Dr Ross, who discovered that malaria parasites were transmitted by mosquitos on 20 August 1897, dubbed Mosquito Day by Ross himself, are revealed for the first time in previously unseen archived letters and documents.

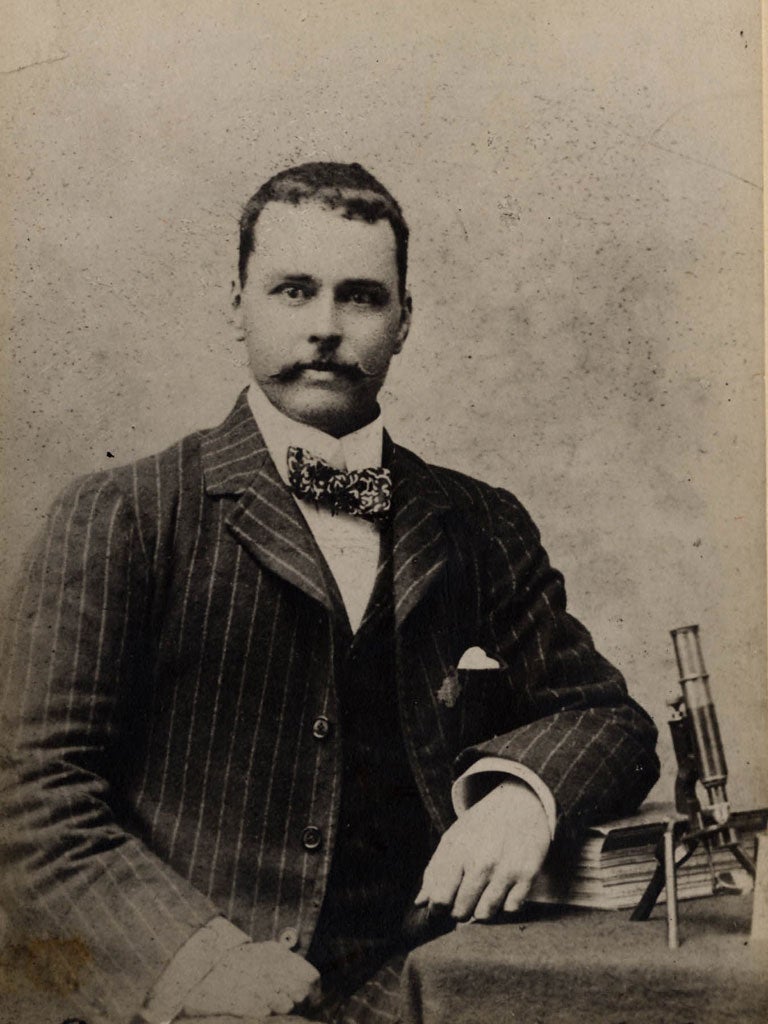

Ross, who was the first Briton to be awarded the Nobel Prize for medicine, discovered the presence of malaria cells in the stomach of a mosquito on a steaming hot afternoon in India, beating a team of Italian scientists to the chase. At which point he became the Father of Malaria.

In his notebook he made rough drawings of the cells seen under his microscope which for the first time established malaria was transmitted through the blood-sucking bugs rather than coughing or close human contact. His notes, books, blood slides and beautiful brass microscope open to the public next Wednesday at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM).

His findings, which included impressive details about the lifecycle of the mosquito and mathematical models that suggested reducing the density to 40 mosquitos per person was enough to disrupt the spread of malaria, laid down the scientific foundation still used in prevention programmes such as insecticide treated nets today.

Ross proved the theory which had been purported by another tropical diseases pioneer, Sir Patrick Mason, but who at the time was mocked by the great and the good as Mosquito Manson. Born in 1844, Manson cut his cloth in China studying all sorts of weird and deadly diseases before founding the world-renowned LSHTM in 1899.

However malaria experts at the LSHTM, who revere Ross and Manson as the forefathers of the disease, are involved in the development of vaccines which build upon the scientific blocks they laid. David Schellenberg, professor of malaria and international, works on Ross’s old desk.

Another scientist, and Olympic gold medal winner, on show at the LSHTM is Jerry Noah Morris, dubbed the inventor of exercise after he became the first doctor to scientifically prove the link between physical exercise and health.

He established that bus drivers, who spent 90 per cent of each working day sitting down, had substantially more heart attacks than their bus conductors who climbed up and down 750 steps a day. He was not convinced by what he’d found until another study involving postal works gave similar results.

In 1953 he published the seminal paper in The Lancet titled ‘Coronary Heart Disease and Physically Activity of Work’, now hailed as the turning point in understanding the causes of ill health and premature death. It was met with scepticism at the time.

Dr Norris, a daily swimmer who died at the age of 99 in 2009, spent almost 50 years at LSHTM investigating health inequalities and persuading governments to introduce public health measures to tackle smoking, air pollution and better primary care. He was awarded the first ever international Olympic medal and prize in exercise science in 1996.

The exhibition runs from 1 August for two weeks

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments