Mothers face ban on taking placenta pills

Eating afterbirth is an ancient practice, but now the EU is considering outlawing the capsules

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.To an unborn child, it's a lifeline; to hospitals, biohazhard waste for the incinerator; to most parents, an element of childbirth they'd really rather forget. But for a growing number of new mothers, including January Jones and Alicia Silverstone, the placenta has become a crucial post-birth ingredient in the battle to ward off post-natal depression and cope with those overwhelming first few months.

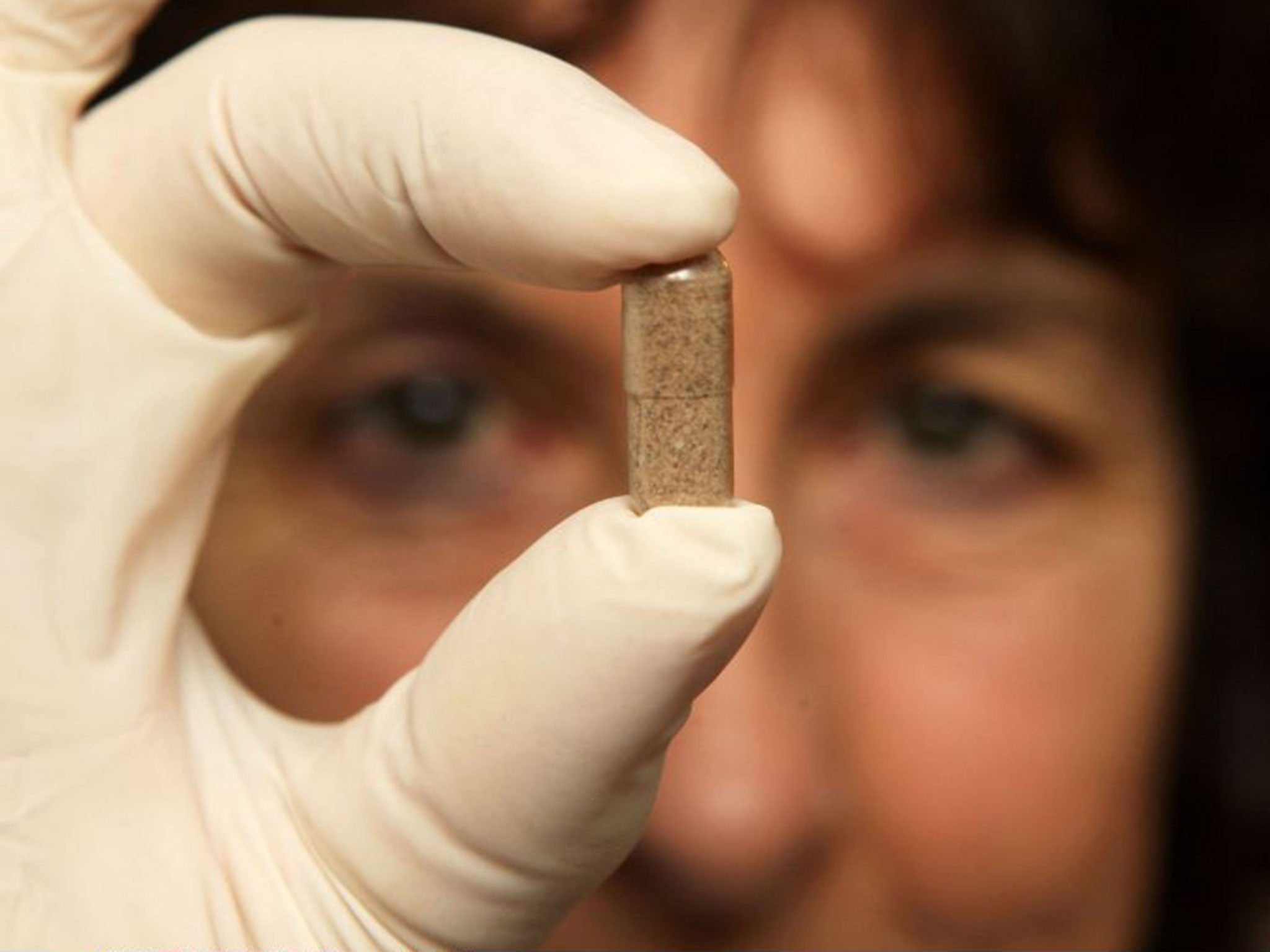

Thousands of women swear by the latest incarnation of the phenomenon: having your placenta encapsulated into easy-to-pop pills that are said to provide an energy boost, restore iron levels, and help breast-milk production.

But a shock ruling last week has put the centuries-old tradition under threat, after the European Food Safety Authority (Efsa) stepped in to classify placenta as a "novel food". Lawyers said the move undermined women's rights to decide what to do with their bodies.

The UK Food Standards Agency has granted a one-month window, until 11 July, for anyone unhappy with the ruling to prove that human placenta is not a so-called novel food. This requires evidence that EU women were eating their placentas before 15 May 1997, the date the European Commission introduced novel food legislation to stop the sale of products derived from GM crops. Today, the term covers anything from exotic fruit and vegetables, such as the baobab fruit, to meat from cloned animals.

It means that from mid-July, anyone offering placenta encapsulation services will be at "risk of prosecution or unlawful marketing of novel food", said Elizabeth Prochaska, a barrister specialising in women's rights for the charity Birthrights.

The ruling threatens the future for 102 members of the Independent Placenta Encapsulation Network (Ipen), a grassroots group of midwives and doulas, or labour coaches, set up three years ago to tap into the trend for eating placenta. Ipen practitioners, who normally work from their own homes, charge £150 for capsules and £25 to make a placenta smoothie.

Carly Lewis, 34, a mother of two who has offered Ipen services for a year, said a blanket ban would be wrong because placentas were not being sold as food. "We're just processing a woman's own placenta."

There is no medical evidence supporting placentophagy, as it's technically known; every woman's placenta is unique, so reported benefits – as recently reported in a University of Nevada study – remain anecdotal. But many cultures, such as the Chinese, have long believed dried placenta to be restorative.

Tanya Hempenstall, 40, from south London, had her placenta dried and made into pills after the birth of her second son, Ryan, which involved a Caesarean section and the loss of 1.5 litres of blood. She said: "My recovery was so quick... [the placenta] is something that's come out of my body, so I should be responsible for the effects it has on me."

Ms Prochaska added: "It's strange to classify something that's part of a woman's physiology as a novel food. Legally it's not very clear cut."

Janet Fyle, a policy adviser at the Royal College of Midwives, said: "Some women who've had post-natal depression find it makes a difference." She added: "Whatever women do in their own home is their business."

The FSA would have to approve any application to sell placenta as a novel food, a process that Ipen said would take up to three years, require extensive laboratory testing, and be very expensive.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments