In silico: First steps towards a computer simulation of the human body

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A pregnant woman undergoing tests in hospital has her biological information plugged into a computer. The results say that she is highly likely to damage her pelvic floor muscles during the birth and will probably suffer from incontinence years later. Armed with this information, doctors intervene to minimise the damage as her baby is born, and the problems are avoided.

It sounds like the sort of predictive healthcare that we cannot expect for decades, but British researchers working on a huge collaborative medical research project have said that advances like this are not far away.

The University of Sheffield’s Insigneo Institute, which was founded exactly a year ago, comprises 123 academics and clinicians who are working towards a grand European Commission-backed endeavour known as the Virtual Physiological Human programme. Collectively, they have already won more than £20 million in research funding.

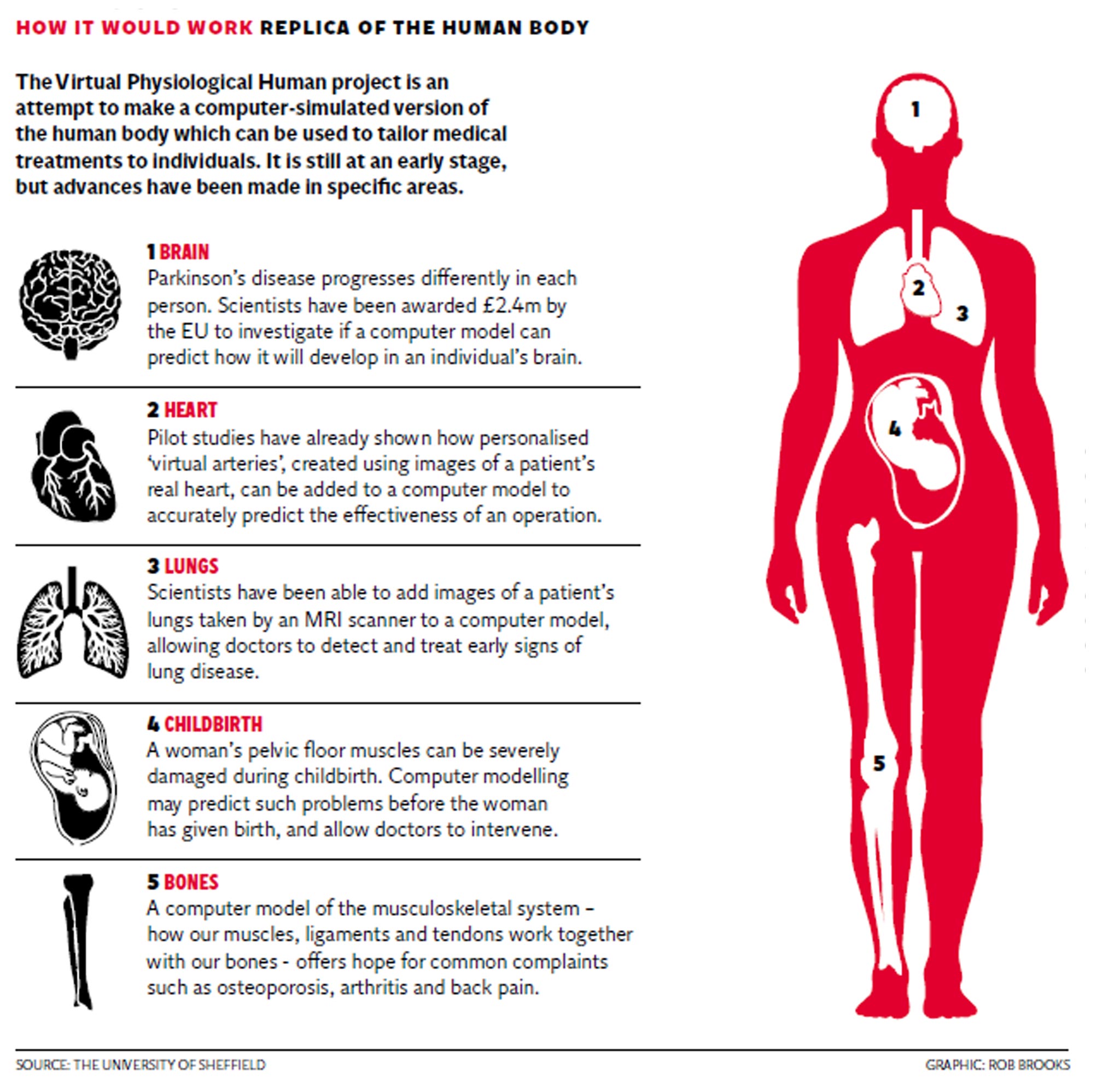

The programme’s ultimate aim is to create an in silico, or computer simulated, replica of the human body that will allow the virtual testing of treatments on patients based on their own specific needs – potentially predicting future problems they may encounter or eliminating the need for invasive procedures.

“Computers are nothing special – they know what we know, and sometimes not even that,” said Marco Viceconti, Insigneo’s scientific director. “But they can stitch things together and they’re not scared by sheer size. If we could know in advance which patient would respond to which treatment, we would just quantum leap our efficacy – without inventing anything. The opportunities are enormous.”

The scientists involved in the project gathered for a progress report. Dr Paul Morris, a research training fellow at the British Heart Foundation, told how his work involved the creation of personalised “virtual arteries” using images of a patient’s actual heart, which can accurately predict how effective an operation – such as the introduction of a stent, commonly used to treat heart disease and angina – might be.

“If you want to know what a stent will do, you have to insert it and then reassess,” he said. “But once you’ve deployed a stent, you can’t take it back – whereas in the in silico world, we can perform a virtual intervention and then assess the physiological impact.”

Jim Wild, a research professor in pulmonary imaging at the National Institute for Health Research, said computer models of a patient’s lungs could allow doctors to detect signs of lung diseases such as emphysema much earlier. “I’d hope within five years this is going to be broadly applicable across the UK,” he said.

Dr Xinshan Li, of the University of Sheffield’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, is researching the impact of pregnancy on women's pelvic floor muscles, and how problems this stores up in the future can be predicted through personalised computer simulations.

“It’s positioned as a predictive tool,” she said. “The idea is to get the geometry of your pelvic floor either during pregnancy or before you become pregnant, and then run simulations of the birth process and see how likely it is that the muscle will be damaged. If the risk is high, then there are certain interventions we can do during the birth process to mitigate the risk.”

Professor Peter Coveney, director of the Centre for Computational Science at University College London, said that using computer models in conjunction with patient data in such ways was “obviously the future of medicine”.

But he added that the idea of each of us having a virtual avatar to predict how our real bodies will react to drugs and other treatment remained an “aspiration” that was still “many years away”, and that “highly political” rows over the handling of patient data may slow down the process down.

He added: “You also start to run into all sorts of philosophical and ethical problems, such as ‘Will this avatar of me tell me when I’m going to die? I don’t want to know’.”

Q&A

What is the Virtual Physiological Human programme?

A huge, collaborative medical research project involving hundreds of scientists across Europe and beyond, with the aim of creating a totally computer simulated version of the human body which can then be used by scientists to test out medical treatments. The idea is that an individual patient’s data could be inputted into the system, so doctors can see how their body will react to treatment before it is given in the real world, or predict how it will react to an event such as childbirth or a broken leg.

Sounds amazing. But where does Britain come in?

The University of Sheffield’s Insigneo Institute is the main centre in the UK for research into this type of technology. It was only founded a year ago but now has 123 academics and clinicians on its books, who have gained more than £20m in funding between them. Some of them are already reporting promising results and are seeking partnerships with industry.

So when can I meet my medical alter-ego?

Sadly, probably not for a while. Early trial results from some of the scientists have suggested that creating computerised versions of a patient’s lungs or heart arteries can help with diagnosis and treatment, but even these are at a very early stage. Joining all the body’s organs together in one working system is a mammoth task and will take many more years.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments