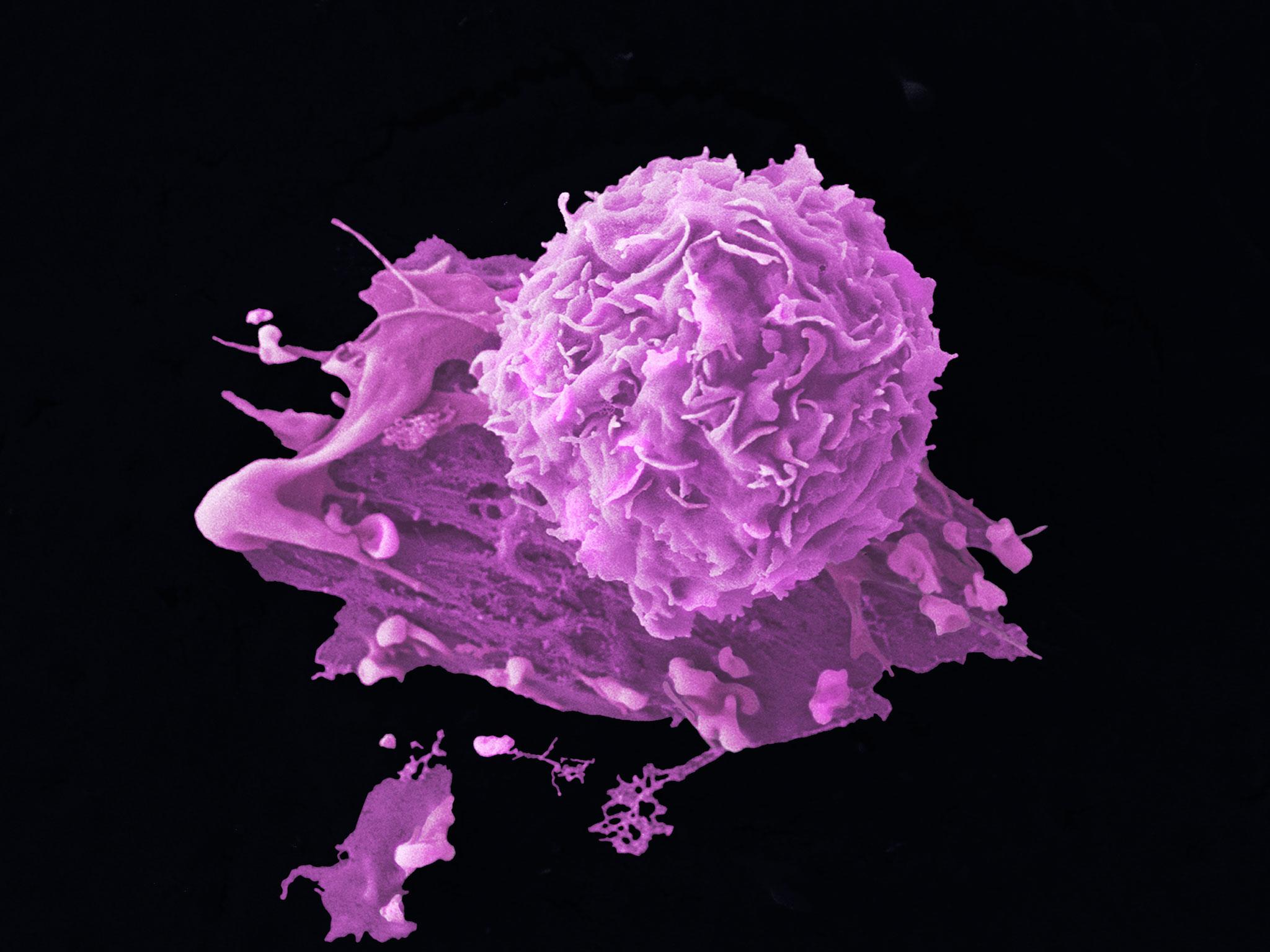

French scientists take 'first steps' towards personalised gene therapy treatment for breast cancer

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Cancer scientists in France have made “one of the first steps” toward the creation of personalised medicines targeted to combat an individual patient’s breast cancer.

By scanning all of the DNA – the entire genome – of more than 400 women with late stage breast cancer for the first time, researchers have provided “proof of principle” that the technique can be used to understand the genetic cause of cancer in an individual, and help design tailor-made drugs to target it.

However, the number of patients whose genetic alterations could be “matched” with new treatments was small – only 13 per cent, and experts cautioned that the number of drug trials underway would have to increase if the dream of “precision medicines” for cancer were to become a reality.

The SAFIR01 trial, led by Professor Fabrice André of the Institute Gustave Roussy in Paris, involved patients from 18 cancer centres in France.

Biopsy samples including at least 50 per cent cancer tumour cells were analysed from 407 patients. It was possible to analyse the entire genome of two thirds of the patients.

Half were found to have a targetable genetic alteration – but in a large number of cases these had no current drug treatment, either undergoing trials or currently available, to be matched with.

“So far 55 of those enrolled have been matched with new treatments being tested in clinical trials,” Professor André said. “This emphasises the need to increase the range of drug trials. Our goal is to have 30 per cent of patients in clinical trials testing therapies targeting the alterations in their tumours.”

The results of the study are published in The Lancet medical journal today.

Dr Kat Arney, science information officer at Cancer Research UK said that while the outcome of the study for patients may have been disappointing, it nonetheless provided proof that whole genome testing for a large group of patients “could be done” and could aid the development of new drugs.

"We already test certain genetic mutations to put patients on targeted drugs, but this is the first time that the whole genome has been tested – this is the future,” she told The Independent. “For several years the field of cancer research and treatment has been moving towards the idea of precision medicine – the idea that you take samples of someone’s tumour, you find out the particular molecular faults that are driving it and then you give them the right targeted treatment.”

However, she said there was “an awful long way to go” before the research would yield widespread benefits for patients, adding that complications such as the ability of cancer cells to evolve resistance to even targeted drug treatments would need to be overcome.

Dr Charles Swanton, from Cancer Research UK’s London Research Institute, said that the study had brought “important insights into the logistical, scientific, and clinical challenges of implementing national cancer genomic assessment”.

However, he said that the patient outcomes were “sobering” and provided “a stark reminder” that understanding of the biological mechanisms behind the spread of advanced breast cancer was still “basic”.

“Efforts to accelerate genomic analyses for personalised medicine must continue to be embedded within the context of clinical trials, and integrated with scientific and clinical collaborative structures to deliver measurable benefits to patients,” he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments