France's dead stars reappear in puff of smoke

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

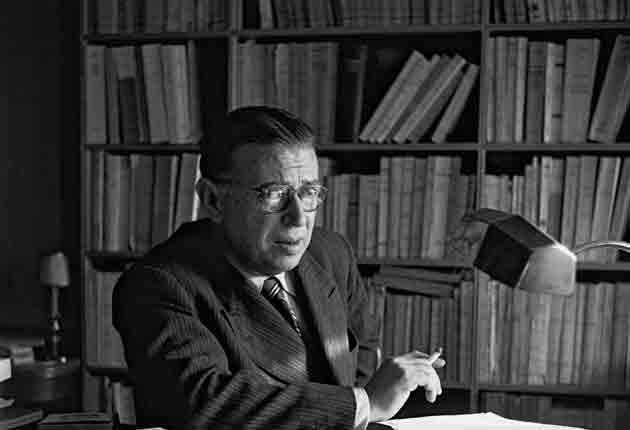

Your support makes all the difference.Jean-Paul Sartre, who died in 1980, will soon be able to smoke cigarettes in public again. And the great comic film-maker Jacques Tati will shortly be allowed to take up his beloved pipe too, 28 years after his death.

French parliamentarians have voted to recommend a "cultural exception" to an anti-smoking law which has led to the "healthily correct" editing of images of celebrated smokers from the past. The cultural affairs committee of the National Assembly decided that such censorship was "worthy only of totalitarian regimes" and priggishly exceeds the spirit of a 1991 law which restricts the advertising of tobacco and alcohol.

If, as expected, both houses of parliament take the committee's advice, dead celebrities in movie or exhibition posters will no longer have to have their cigarettes or pipes amputated. The issue became an international cause célèbre in 2009 when a Paris festival for the centenary of Jacques Monsieur Hulot Tati was ordered to remove the actor and director's celebrated pipe from an advertising poster. The festival organisers suggested the offending object should be replaced with the words, "This is a pipe" (recalling a painting by the surrealist artist René Magritte). Even this was refused, as a form of tobacco promotion. So the organisers used a poster of Tati cycling with a child's toy windmill gripped in his teeth.

In 2005, the French existentialist philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre – the apostle of individualism and self-made morality – was forced, posthumously, to stop smoking. A poster for an exhibition on his centenary at the Bibliothèque Nationale used a celebrated image of Sartre with a cigarette drooping from his lower lip. The cigarette was, however, missing.

The campaign began in 1996 when the postal service published a stamp with the image of the writer André Malraux, who died in 1976. His habitual cigarette had been removed.

There have also been recent incidents of censorship, involving posters for films about two other celebrated, and long-deceased, chain-smokers, the fashion designer Coco Chanel and the singer and song-writer Serge Gainsbourg.

The 1991 law banned all images of smoking and most images of drinking from French adverts. No prosecution has ever been brought against a film or exhibition poster with an "old" smoking image but advertising agencies have imposed self-censorship on their clients.

Even the man who sponsored the original law, the former health minister Claude Evin, has criticised the editing of the Sartre and Tati posters as "absurd" and "excessive". A Socialist member of parliament, Didier Mathus, drafted an amendment to the law which allows a more "subtle" approach for "cultural works" which include images of smoking.

In other words, a tobacco company could still not use pictures of Jean-Paul Sartre to sell cigarettes; a film company or museum could use a picture of a smoking Sartre to publicise a movie or exhibition. Mr Mathus said the anti-smoking law was being used to create "grotesque reinterpretations and falsification of a history" worthy only of a totalitarian state.

The state-sponsored anti-smoking body, L'Office Français du Tabagisme (OFT) urged members of the culture committee of the National Assembly to reject the change. The controversy was being exploited by the tobacco lobby, the OFT said, to create a breach in the law which could be widened later.

All but one member of the committee voted this week to approve the amendment and send it to the upper and lower houses of parliament.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments