Exercise changes the way our bodies work at a molecular level

You don’t have to do high-impact workouts to keep your body healthy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Exercise is good for you, this we know. It helps build muscle, burn fat and make us all into happier, healthier people. But long before you start looking the way you want, there are other hidden, more immediate, molecular and immunological changes taking place inside your cells. Changes that could be responsible for protecting us from heart disease, high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes – and even stave off old age and cancer.

You may think that “molecular” changes may not be that much of a big deal. Surely it is fat loss and muscle gain that are the best outcomes of exercise? Actually molecular changes affect the way genes and proteins are controlled inside cells. Genes can become more or less active, while proteins can be rapidly modified to function differently and carry out tasks such as moving glucose into cells more efficiently, or protect cells from harmful toxins.

Type 2 diabetes causes all kinds of health problems, including cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, blindness, kidney failure and nerve damage, and may lead to limb amputation. The underlying cause is the development of a heightened inflammatory state in the body’s tissue and cells. This damages cells and can eventually lead to insulin resistance and, ultimately, type 2 diabetes.

The main risk factors for type 2 diabetes include obesity, a poor diet and a sedentary lifestyle. However, we have found that even low-intensity exercise, such as brisk walking, can increase the body’s insulin sensitivity. This means that people at risk of developing diabetes become less prone because they are able to metabolise glucose more efficiently.

In our study we asked 20 sedentary people who were at risk of developing diabetes to walk briskly for 45 minutes, three times a week, for eight weeks. Although there was no change in their weight, blood pressure or cholesterol level, on average each participant lost a significant six centimetres from their waist circumference. And, more importantly, there was a reduction in their diabetic risk.

Immune system benefits

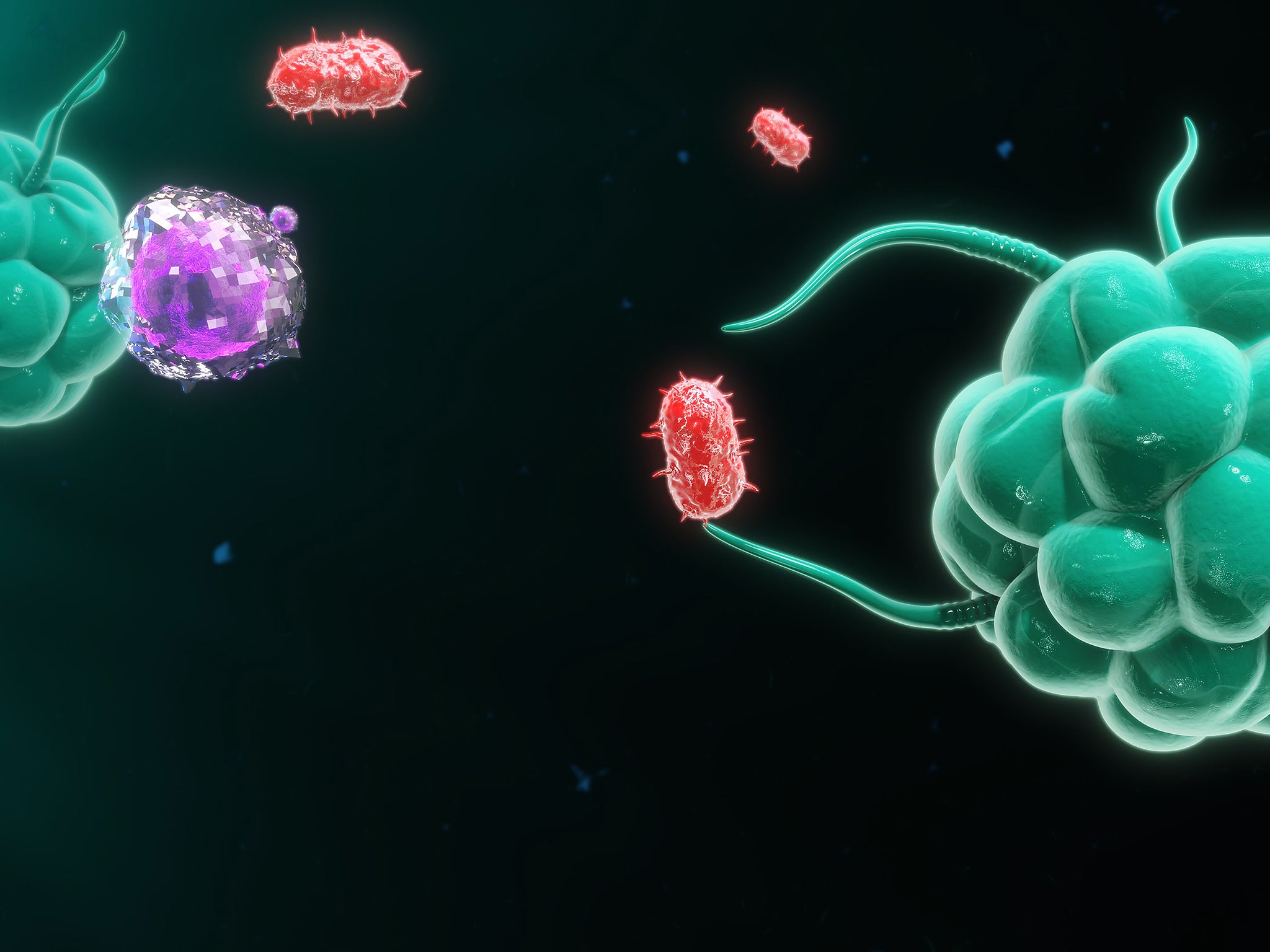

Interestingly, there were also exercise-induced changes in the participants’ monocytes – an important immune cell that circulates in the bloodstream. This led to a reduction in the body’s inflammatory state, one of the main risks for type 2 diabetes.

When our body is under attack from foreign invaders such as microbes, immune cells such as monocytes change into “microbe-eating” macrophages. Their main function is to fight infection in our tissues and lungs. There are two main types of macrophages, M1 and M2. M1 macrophages are associated with pro-inflammatory responses and are necessary for aggressively fighting off infections. However, in obese people who do not exercise, these cells become active even in the absence of infection. This can lead to an unwanted, heightened inflammatory condition which may “trigger” diabetes.

On the other hand, M2 macrophages play a role in “switching-off” inflammation and are instrumental in “damping-down” the more aggressive M1s. So a healthy balance of M1 and M2 macrophages is crucial to maintain an optimal immune response for fighting infections – and it may help prevent the heightened inflammatory condition which comes from lack of exercise and obesity too.

Other studies have also shown that exercise has a beneficial impact on tissues’ immune cell function and can reduce unnecessary inflammation. Exercise training in obese individuals has been found to reduce the level of tissue inflammation specifically because there are less macrophage cells present in fat tissue.

In addition, researchers have found a significant link between exercise and the balance of M1 and M2 macrophages. It has been shown that acute exercise in obese rats resulted in a shift from the “aggressive” M1 macrophages to the more “passive” M2 – and that this reduction in the inflammatory state correlated with an improvement in insulin resistance.

Time to move

There is no definitive answer as to how much and what intensity of exercise is necessary to protect us from diabetes. Though some researchers have shown that while higher-intensity exercise improves overall fitness, there is little difference between high and low-intensity exercise in improving insulin sensitivity.

However, a new study has found that all forms of aerobic exercise – in particular high-intensity interval training such as cycling and running – can effectively stop ageing at the cellular level. The exercise caused cells to make more proteins for their energy-producing mitochondria and their protein-building ribosomes. Researchers also observed that “molecular” changes which occur at the gene and protein levels happened very quickly after exercise and that the effects prevented damage to important proteins in the cells and improve the way in which insulin functions.

Although you might not see the changes you want immediately, even gentle exercise can make a big difference to the way the body’s cells behave. This means that exercise could have far-reaching health benefits for other inflammatory associated diseases and possibly protect us against ageing and cancer too.

principal lecturer at Cardiff Metropolitan University. This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments