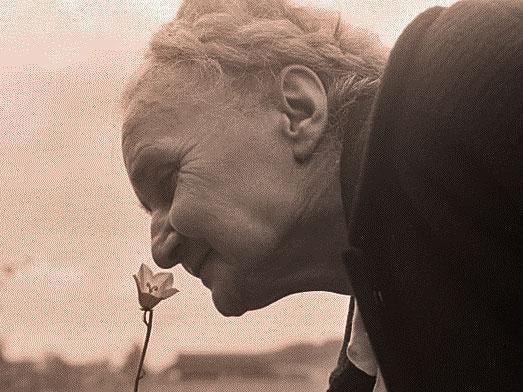

Losing sense of smell in later life could be early sign of dementia, scientists warn

Experts also stress people can lose the sense for a number of reasons

Losing the ability to smell peppermint, fish, orange, rose and leather could be an accurate early warning sign of dementia, according to a new study.

The ability of nearly 3,000 people aged 57 to 85 to detect these five odours was tested by scientists.

When they returned about five years later, almost all of the people who had not been able to name a single one of the five scents had dementia, as did nearly 80 per cent of those who gave only one or two correct answers.

However other experts said people could lose their sense of smell for other reasons with one writing that the study did not support the idea that “smell testing would be a useful tool for predicting the onset of dementia”.

One of the researchers, Professor Jayant Pinto, of Chicago University, said: “Loss of the sense of smell is a strong signal that something has gone wrong and significant damage has been done.

“This simple smell test could provide a quick and inexpensive way to identify those who are already at high risk.

“Of all human senses, smell is the most undervalued and underappreciated – until it’s gone.”

However he added: “Our test simply marks someone for closer attention. Much more work would need to be done to make it a clinical test. But it could help find people who are at risk. Then we could enrol them in early-stage prevention trials.”

In the study, 78 per cent of those tested had a normal sense of smell, correctly identifying either four or five of the odours.

Nearly 19 per cent got two or three out of five correct, while 2.2 per cent could only identify one and one per cent were unable to tell what any of the scents were.

“These results show that the sense of smell is closely connected with brain function and health,” Professor Pinto said.

“We think smell ability specifically, but also sensory function more broadly, may be an important early sign, marking people at greater risk for dementia.

“We need to understand the underlying mechanisms so we can understand neurodegenerative disease and hopefully develop new treatments and preventative interventions.”

A paper describing the study was published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.

In 2014, researchers found that loss of the sense of smell was associated with increased risk of death within five years. The study appeared to show it was a better predictor of death than a diagnosis of heart failure, cancer or lung disease.

The loss of the sense can affect people’s wellbeing, lifestyle, nutrition and mental health.

“Being unable to smell is closely associated with depression as people don’t get as much pleasure in life,” Professor Pinto said.

Fellow researcher Professor Martha McClintock, also from Chicago University, said: “This evolutionarily ancient, special sense may signal a key mechanism that also underlies human cognition.”

She added that the olfactory system has stem cells which self-regenerate so “a decrease in the ability to smell may signal a decrease in the brain’s ability to rebuild key components that are declining with age, leading to the pathological changes of many different dementias”.

However, in an editorial in the journal, another expert Dr Stephen Thielke, of Washington University, wrote: “Olfactory dysfunction may be easier to quantify across time than global cognition, which could allow for more-systematic or earlier assessment of neurodegenerative changes, but none of this supports that smell testing would be a useful tool for predicting the onset of dementia.”

And Rosa Sancho, head of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK, stressed there were other reasons why people could lose their sense of smell.

“Smell is our most primitive sense and humans can distinguish up to a trillion different odours. This study links difficulties in recognising smells with a greater dementia risk five years later, adding to existing evidence that smell could act as an early warning sign for the condition,” she said.

“Scent cells in our noses feed directly into the brain and we know that diseases like Alzheimer’s can start to damage the brain around a decade before symptoms show.

“While it’s possible that early damage caused by diseases like Alzheimer’s could interfere with a person’s ability to smell, it isn’t always an early symptom of dementia and there are many reasons why someone’s sense of smell could change.”

But she added that the charity is investigating the potential link between the sense of smell and dementia.

“Smell tests are already being explored in our Insight 46 study, a landmark UK research study of 500 people aged 71, to understand more about changes in smell in ageing and dementia,” she said.

“While smell tests could help to flag up wider concerns, they’d need to be used alongside other, more specific diagnostic tests if they were to aid the early detection of dementia in future.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks