Why chlamydia could make you blind

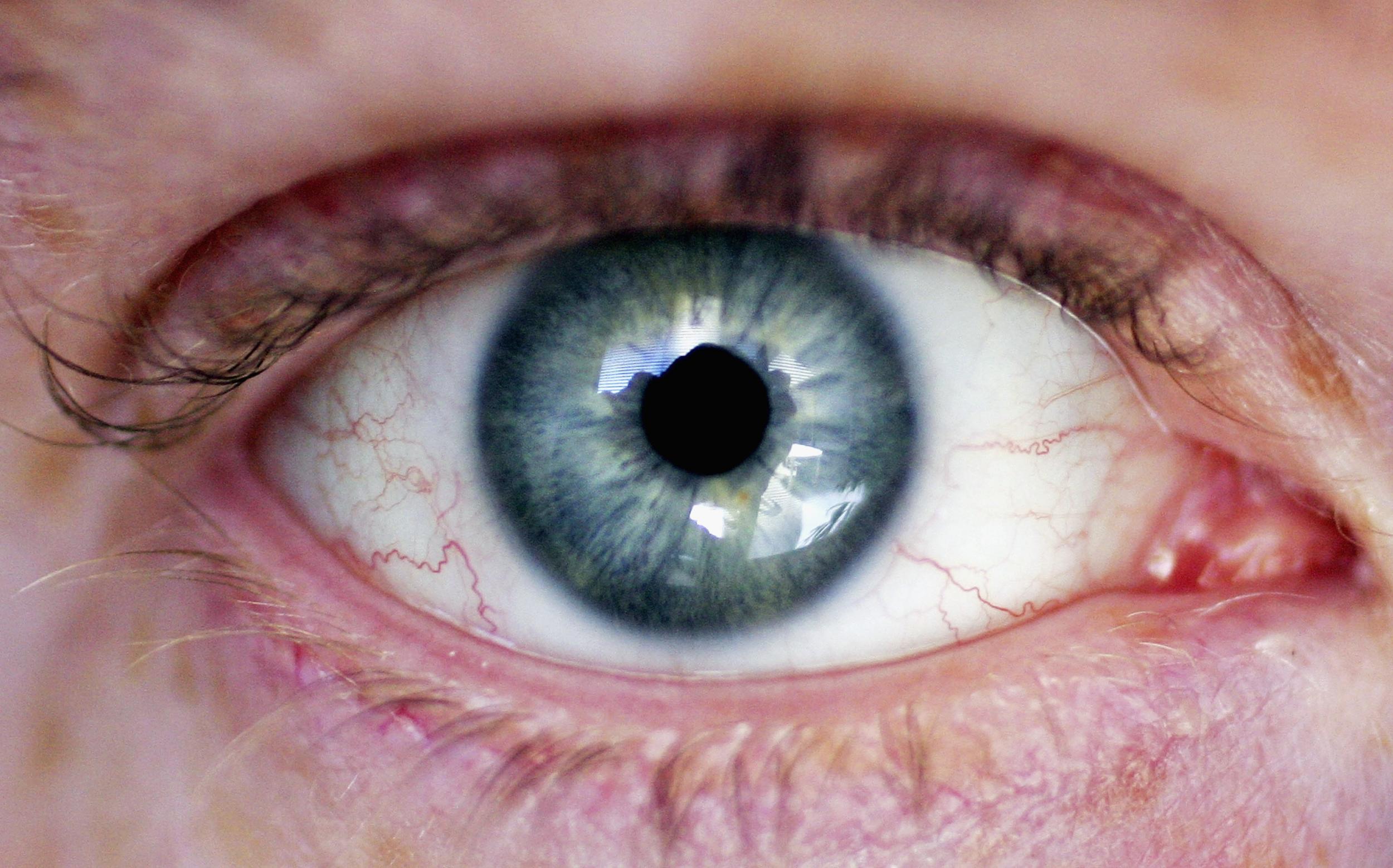

Trachoma causes the eyelid to turn inward, making the eyelashes scratch against the cornea and causing immense pain, followed by blindness

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A bacteria that induces blindness could be transmitted along with chlamydia, new research has suggested.

Trachoma is an extremely painful tropical disease that causes the eyelid to turn inward. This prompts the eye to blink 10-25 times a minute, causing relentless pain as the eyelashes scratch the cornea, eventually resulting in loss of sight.

A strain of chlamydia has long been known to cause trachoma, but scientists had previously believed the two strains to be separate.

Now, however, research published in Nature Communications has suggested it is possible for one strain to transform into the other, depending on genetic variations. Researchers found that just one or two genetic variations could cause an STD to morph into a strain associated with blindness. This suggests that the blindness strain could be transmitted sexually along with chlamydia.

The research is a joint project by scientists from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and the Menzies School of Health Research in Australia.

Lead author Dr Patiyan Andersson said: “This work came about from the analysis of frozen isolates that had been collected in the 1980s and 1990s. We were able to resuscitate chlamydia that had frozen for 30 years, and study their genomes to find out how they had evolved.”

Co-author Dr Phil Giffard said: “The sequences of these strains were the biggest surprise of my scientific career to date. They were completely different to how they ‘should’ have been. Surprises are what every scientist hopes for.”

Chlamydia is one of the most common sexually transmitted diseases in the UK. According to the NHS, some 200,000 people are diagnosed with it every year. It is primarily transmitted through oral, anal or vaginal contact with infected genitals, and can also be transferred between a pregnant woman and her foetus.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments