One in five breast cancer patients not receiving new treatment that could benefit them, scientists say

Some 8,000 more patients may respond to the drugs than are receiving them at present

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Up to one in five women with breast cancer could benefit from a type of treatment currently only given to patients with a rare form of the disease caused by gene mutations, scientists have said.

Drugs designed to treat less common cases of breast cancer driven by faults in tumour-suppressing BRCA genes may also help women with more common forms of the disease, according to a new study.

Researchers from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute found some 8,000 more patients may respond to the drugs than are receiving them at present.

Around one to five per cent of the the 55,000 women diagnosed with breast cancer in the UK each year are thought to have BRCA-driven disease.

Actor Angelina Jolie underwent a double mastectomy when she discovered she had inherited a faulty gene known as BRCA1, which meant she had an 87 per cent risk of developing breast cancer.

The scientists said thousands of more common forms of breast cancers were biochemically similar to these rarer cases involving BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations.

“Our study shows that there are many more people who have cancers that look like they have the same signatures and same weakness as patients with faulty BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes,” said lead researcher Dr Serena Nik-Zainal.

Dr Nik-Zainal said these women may respond to a class of drugs known as PARP inhibitors that are are specifically designed to target tumours with the defective genes. “We should explore if they could also benefit from PARP inhibitors,” she said.

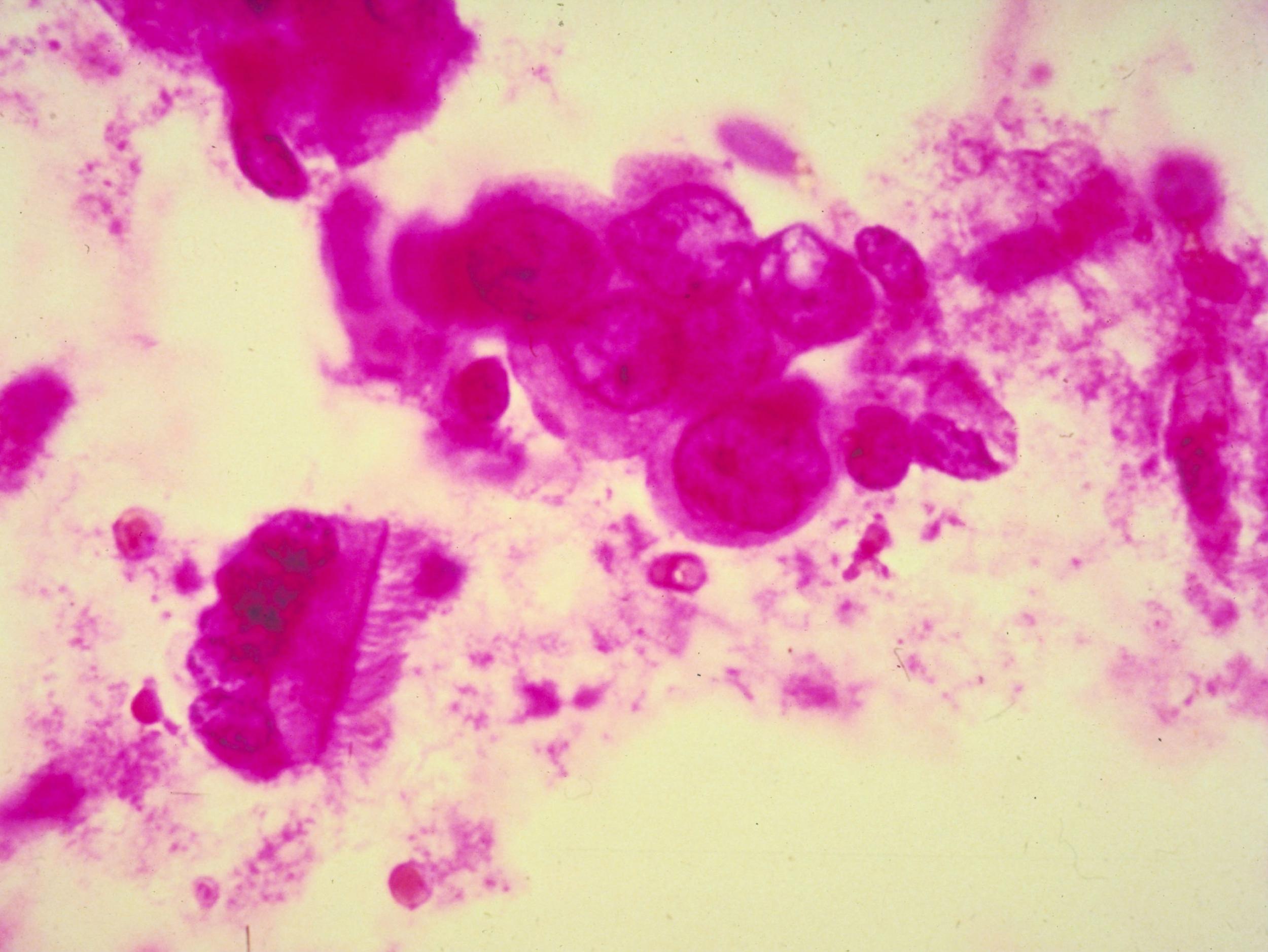

The team, whose results are published in the journal Nature Medicine, analysed DNA from breast cancer tissue samples taken from 560 patients.

A piece of computer software called HRDetect was used to identify genetic code “fingerprints” revealing biochemical pathways like those associated with mutant BRCA1 and 2 genes.

Of the total group of patients, 22 had previously diagnosed BRCA 1 and 2 mutations. Another 55 had unexpected BRCA mutations, including some very unusual ones that were not inherited.

A further 47 had BRCA genes with no recognised mutations, yet in these patients the repair mechanisms controlled by the genes were still faulty.

“It's possible there are other ways of turning off BRCA 1 and 2 that we don't understand, perhaps involving other genes,” said Dr Nik-Zainal.

She added: “PARP inhibitors are important for quality of life because they specifically target cancer cells and so are well tolerated.

“I feel so strongly about the fact that one in five women might benefit from these drugs. A lot of people who could be getting these treatments are not being offered them.”

But she pointed out that a lot more evidence had to be collected before guidelines on the use of PARP inhibitors could be changed.

Baroness Delyth Morgan, chief executive of the charity Breast Cancer Now, said she hoped the findings could lead to a “watershed moment” in the treatment of the disease.

“PARP inhibitors are a very promising treatment on the horizon and the suggestion that more patients may be able to benefit from them is greatly exciting,” she said.

“Crucially, this study is an early but encouraging step towards being able to offer women treatments targeted to the genetic make-up of their breast cancer.

“The discovery that many women may have tumours genetically similar to patients with faulty BRCA genes, without them actually having a BRCA mutation, is somewhat of a revelation.”

Additional reporting from Press Association

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments