How the throat acts as a ‘silent reservoir’ for gonorrhoea

Doctors may have to resort to ‘off-label’ treatments that haven’t been properly tested in humans

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The human throat houses billions of bacteria, most of them harmless. But one species is becoming more common, and it is anything but benign.

Drug-resistant gonorrhoea has been on the rise for years; the World Health Organisation has reported an increase in more than 50 countries. Now scientists say the epidemic is being driven by a particular mode of transmission: oral sex.

“The throat infections act as a silent reservoir,” says Emilie Alirol, the head of the sexually transmitted infections programme at the Global Antibiotics Research and Development Partnership. “Transmission is very efficient from someone who has gonorrhoea in their throat to their partner via oral sex.”

Oral gonorrhoea is hard to detect and treat. Even more worrisome, these bacteria pick up resistance to antibiotics directly from other bacteria in the throat – and then are communicated to sex partners.

Only one commercially available antibiotic still consistently works against drug-resistant strains. And now there’s a new worry: so-called super gonorrhoea, impervious to every standard treatment.

“This bug always outsmarts us,” says Dr Jeanne Marrazzo, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “It’s really good at figuring out ways to become resistant.”

Whenever the human body is exposed to antibiotics – for an ear infection, a sore throat or any other illness – the natural bacteria of the throat are exposed, too. Over time, they can build up resistance to the drugs.

That is generally not a concern until harmful bacteria are introduced. Sharing close quarters with the natural occupants of the throat, the invaders exchange DNA in a process called horizontal gene transfer.

This process relies on plasmids, small circular DNA molecules that contain the bacterium’s genetic material but are separate from chromosomes. Plasmids can easily be transferred from one bacterial species to another when they are close by.

When the plasmid in question contains drug-resistant genes, the gonorrhoeal bacteria acquiring it become resistant to antibiotics, too. Thirty per cent of all new gonorrhoea infections in the United States are resistant to at least one drug, according to the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, and studies show that gene transfer is largely the reason.

“The worry is that if we don’t stop this, if we don’t treat it properly, we’re going to see this happening more and more,” says Dr Michael Mullen, an infectious disease specialist at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

Worldwide, gonorrhoea infects about 78 million people each year. The number has been rising in recent years, partly because of decreasing condom use as fear of HIV transmission has waned, and because of poor detection rates, failed treatments and increased travel as people carry drug-resistant strains from one country to another, according to the WHO.

Drug-resistant strains have increased in many countries in recent years, most notably in India, China, Indonesia, parts of South America, Canada and the United States. Little is known about trends in Africa or the Middle East because of a lack of consistent data.

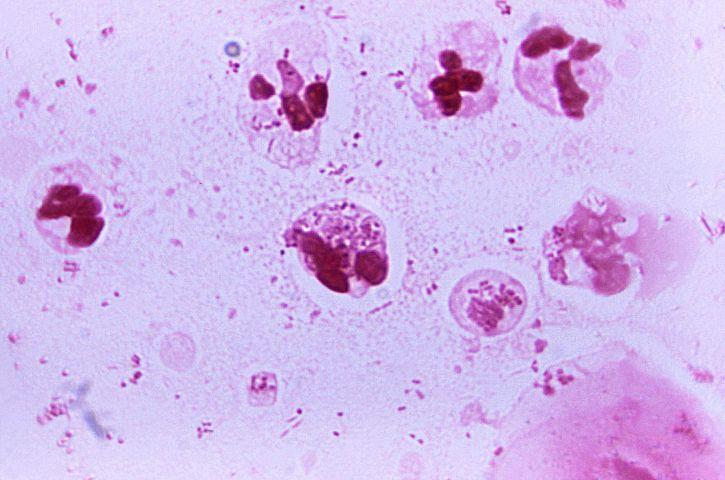

Diagnosing oral gonorrhoea typically involves taking a sample from the infected area and growing the bacteria in a lab.

But swabs from the throat often do not yield enough bacteria and they frequently do not grow. There are typically fewer gonorrhoea bacteria in the throat than in the genitals, making the infection easier to overlook in the lab.

Even when detected, oral infections are harder to treat. Antibiotics are delivered in the bloodstream, but there are fewer blood vessels in the throat.

Untreated throat infections can spread to the genitals, where they can cause testicular and pelvic pain in men, and can be particularly dangerous for women, causing pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancies and infertility.

“Women will bear a very high burden if we start having an increasing number of untreatable gonorrhoea cases,” Alirol says.

The infection used to be cured by a variety of antibiotics, but the bacteria adapt quickly. Some strains have built up resistance to all but one treatment: an injection of an extended-spectrum cephalosporin paired with the an oral form of azithromycin.

Even that is no longer a sure bet. There have been three cases of so-called super gonorrhoea – in Japan, France and Spain – that resisted that treatment, too.

That does not necessarily mean that super gonorrhoea is incurable, Alirol says. But doctors may have to resort to “off-label” treatments that haven’t been properly tested in humans – much higher doses of antibiotics, for instance, or older or stronger drugs.

“The problem of using off-label tools is that you don’t know which dose to give, or if it’s going to work,” Alirol says. “You want to keep these as last-resort tools. If you start giving them away, you will develop resistance to them, too.”

Researchers are currently working on three new drugs to treat gonorrhoea, each in various stages of development. But beyond that, there are not many options for resistant gonorrhoea.

There is not much incentive for pharmaceutical companies to develop new treatments. Unlike medicines for chronic diseases, these are only taken for short periods of time, and new drugs constantly need to be replenished as resistance builds up to the old ones.

None of the new drugs focus on effectively curing oral gonorrhoea, Alirol says. It is the form that is detected least often, so people are less likely to seek treatment for it.

But it is also at the root of a growing public health problem.

“There is no use in developing a new treatment if it doesn’t work on the pharynx,” Alirol says. “You will not have an effect on the numbers.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments