'Thalidomiders': still fighting for justice

Fifty years after the Thalidomide scandal, its victims' compensation funds are dwindling. Jeremy Laurance meets Nick Dobrik, whose extraordinary campaign aims to give them dignity and independence in old age

If you have ever taken a headache remedy, swallowed an antibiotic, sucked on an asthma inhaler, been injected with a cancer medicine or taken any drug developed in the last half century, you owe a debt to Nick Dobrik and the thousands like him who paid, in some cases with their lives, for your safety.

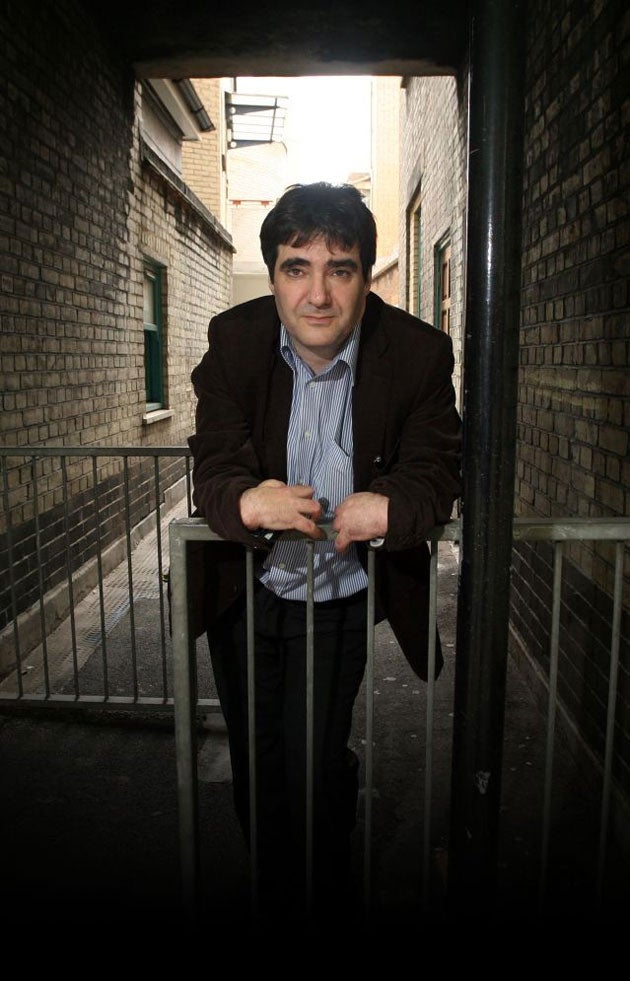

Mr Dobrik is an ebullient 49-year-old with an open face, black hair flecked with grey, thick eyebrows gone awry, and a lot to say. He talks fast and urgently, anxious to impart as much information as possible, knowing he must soon move on to the next receptive ear to spread his message.

He wears a thick black coat and open-necked blue shirt on this shivery May morning, sitting with a coffee outside Starbucks in Hampstead, north London. You have to look closely to see his distinguishing feature – foreshortened arms with twisted hands that turn dramatically inwards. During our two-hour conversation, surrounded by gossiping students and mums with pushchairs, he repeatedly pushes the over-long arms of his coat back, to keep his hands free. But you do not get a sense of his disability until he struggles to retrieve an envelope from the inside pocket of his coat. Then he stands and executes a strange bowing and twisting movement, like a mechanical digger delving for the document deep inside his clothing.

He is a "Thalidomider" – a survivor of the world's worst drug disaster, caused by a medicine prescribed to pregnant women as a treatment for morning sickness in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Some 10,000 babies worldwide were born with deformities as a result, before the drug was withdrawn in 1961.

Unlike medicines today, Thalidomide was not subjected to rigorous testing before it was launched. There were few laws governing drugs in the 1950s and its maker, the German company Grunenthal, marketed it as an over-the-counter treatment, available without a prescription, for morning sickness and stress, respiratory infections, and as a sedative for children.

It was its use by pregnant women that proved catastrophic. Even a single dose of the drug, taken at a crucial moment in pregnancy, was enough to interfere with the development of the foetus, causing appalling disabilities. It had never been tested for its teratogenic effects – disturbance to the growth of the embryo – a situation that would be unthinkable for a drug launched today.

Fifty years on, the huge edifice of drug regulation, which requires new medicines to undergo elaborate safety testing in randomised clinical trials, can be traced back to Thalidomide. It is only because of Thalidomide that medicines today are, relatively, safe. The children damaged by Thalidomide half a century ago, who are now entering middle age, remain living testimony to the perils of an unregulated medicines market.

In the UK there are 457 surviving Thalidomiders. They range from the mildly affected to those who have no arms or legs, "flippers" for hands and feet and who are dependent for every aspect of daily living on others. As they age, their needs are growing.

With increasing needs come increasing expenses. It is this fact that has prompted the Thalidomiders, led by Nick Dobrik and his friend Guy Tweedie, with the support of philanthropist Jonathan Stone, 71, to launch a new campaign for increased state help from the Government to bolster the compensation that they say is now inadequate. They have the backing of veteran disability campaigner Lord (Jack) Ashley, and 139 MPs have signed an Early Day Motion in support.

In the UK, the Thalidomide Trust was set up in 1973 with £20m donated by Distillers (the company which distributed the drug here) to support the Thalidomiders after a long and bitter campaign led by The Sunday Times – regarded by many as that newspaper's finest hour.

Over the ensuing decades the sum has been topped up as experience showed it would be inadequate to sustain the Thalidomiders for the rest of their lives. An actuarial report ordered by the Trust in 1993 concluded that the fund would run out by 2009, as a result of which Guinness, which bought Distillers in the mid-Eighties, agreed to pay an extra £2.5m a year to 2009 , later extended by Guinness's successor, Diageo, to 2022.

That deal was done in the mid-Nineties, but it still wasn't enough. The Thalidomiders were living much longer than expected, their disabilities were growing as a result of limbs being used in ways for which they were not designed, and their expenses – electric wheelchairs, adapted cars – were growing. What they lacked was an economist with the brains to up their game in negotiations.

Nick Dobrick filled that bill perfectly. Born into a comfortably-off Jewish family in north London, he was educated at Mill Hill public school and Cambridge before spending four years with the accountancy firm Touche Ross. Then his father had a stroke and he took over the family antique jewellery business, where he is chief executive.

He had never met another Thalidomider in his life until, in 2002, he read a newspaper article about the financial problems faced by the Trust. "I wasn't interested in meeting other Thalidomiders. I played rugby at school and I just wanted to get on with my own life. But when you have been born with a silver spoon in your mouth you have got to put something back. I have had a very lucky life, but since the day I read that article in November 2002, I have been fighting [for a better deal for the Thalidomiders]."

Married with two teenage children, he is warm, engaging and mischievous, telling jokes and anecdotes about the guerrilla tactics he has employed. On one occasion, when the German ambassador refused to see him, he booked a table at the British-German Association dinner (tickets £750 a head) , took along 10 Thalidomider friends, and sent the female members of his party purring across the floor of the Intercontinental hotel in their wheelchairs to request the ambassador's hand for the next dance. Afterwards the mortified man was putty in his hands.

He says the way to succeed in lobbying is to be nice. Asking for the ambassador's hand at a dance works better than confronting him with placards outside (though there is a place for that too). It takes stamina but it works.

His first campaign was to correct a tax anomaly whereby Thalidomiders who were worst affected and needed cash from the Trust as income were taxed on it, while those, like himself, who were less badly affected, and needed only the occasional lump-sum payment for a wheelchair or car, avoided tax.

"I ran a quick campaign, wrote to every MP and saw 150 face-to-face. We set up an all-party group. We got the tax exemption in 2004."

Next, he helped negotiate an improved deal with Diageo, signed in 2005, which boosted the sum available in the trust fund back to its 1973 value, with a 3 per cent annual increase in real terms from now to 2022, and then maintained at that level for the rest of the Thalidomiders' lives.

That deal, which ran to 70 pages, is said to be worth £160m. It sounds a big number but, according to Dobrik, it is equivalent to an increase of just 45 per cent in real terms over 50 years on the value of the original 1973 settlement – when the rest of the working population has seen vastly greater increases in its standard of living.

Importantly, even after all these rises, the average payment to the Thalidomiders from the trust fund is £18,000 a year, with the most severely disabled receiving up to £36,000 a year. None of the deals has ever been based on the Thalidomiders' needs, and only a quarter of them still have jobs.

"They are not working, they have increasing costs of disability to cope with, they have no pensions, and their parents, who may have looked after them all their lives, are dying. An average income of £18,000 a year is nowhere near enough. An electric wheelchair costs £18,000 and lasts two years. Adapting a car doubles its price. If somebody lost their arms in an industrial accident I wouldn't be surprised if they got an income of £70,000 to £80,000," he says.

For the latest stage of the campaign, Dobrik has turned his attention to the UK Government, which, he says, has taken more from the Thalidomiders in tax on their income payments (£17.8m in total) than it has given in lump sums to the Thalidomide Trust (£12.8m).

Governments in other countries have agreed payments to Thalidomiders which have been made, in some cases, for years – Germany, Italy and Ireland are cited as examples. Overall compensation levels are higher in Britain, thanks to the success of negotiations with the companies that distributed the drug, but "you can't measure the success of one inadequate settlement by pointing to an even more inadequate one," Dobrik says. It is time, he adds, that the British Government did the decent thing.

"It is ridiculous that 50 years after the events we are still fighting for justice. When you take welfare payments, you are a beggar. But this didn't have to happen – it could have been avoided. This is not about entitlement, it is about justice."

"The least you can do for the Thalidomiders is allow them some independent life. They are very few in number but their needs are very great. It won't take much to help them have an independent existence in the last third of their lives."

"What society needs to remember is that the Thalidomiders have suffered their disability from year zero, but almost everybody will suffer it at some point – usually at the end of their lives. It will happen to everyone sooner or later."

"The Government can ignore us, they can bury their heads in the sand, but sooner or later they will have to sit down and talk to us."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks