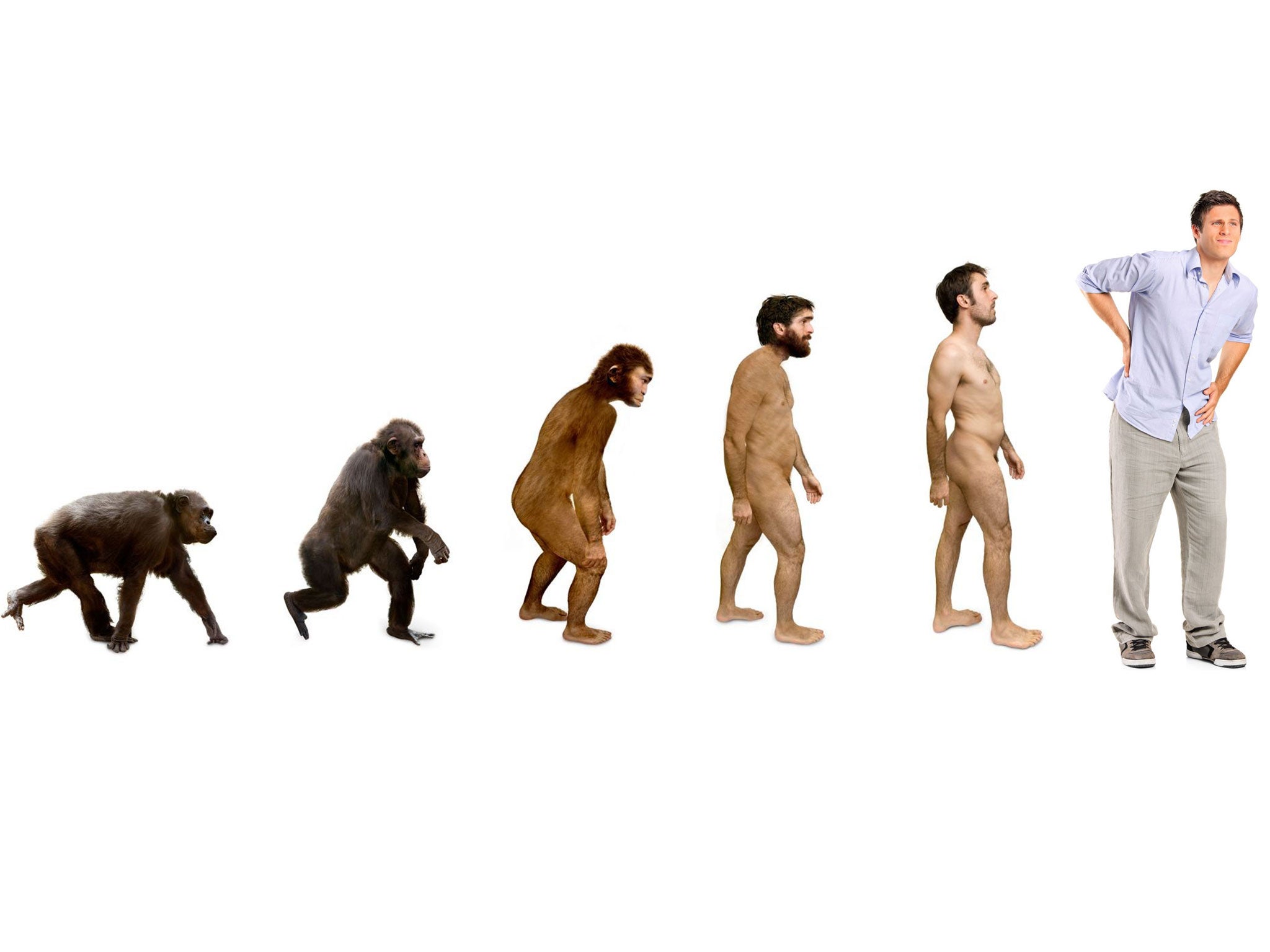

Survival of the unfittest

From allergies to diabetes, the modern diseases that plague us were unknown to our hunter-gatherer forebears. So what can we learn from them?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As recently as 600 generations ago, our species were hunter-gatherers. They would walk and run nine to 15km a day. They would eat fresh food that was high in fibre and low in sugar. And they would spend much of their time nursing, napping and resting. Even simple everyday items such as shoes, books, and chairs were unknown. Quite different to modern day life, then.

Dan Lieberman, a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University, argues that our 21st-century lifestyles are out of synch with our Palaeolithic bodies, and that is leading to trouble. We might be living longer than ever before, with lower infant mortality rates, but we are also prone to a huge number of problems, ranging from less serious ailments such as flat feet (from wearing shoes), having to wear glasses because of the rise of myopia (caused by all that reading), and lower back pain (those damn chairs), to the increase in allergies, as well as far more serious diseases such as diabetes, obesity, heart disease and certain types of cancer. Most of these, until recently, were extremely rare or even unknown, and, what's more, many are preventable.

Lieberman's new book, The Story of the Human Body: Evolution, Health and Disease argues that if you want to find solutions to these modern ailments, you have to consider evolution. “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution, and that includes the good and the bad things about being a human today,” insists Lieberman. “We can't change the bodies that we inherited. We're stuck with them, like it or not. But by understanding and thinking about the evolutionary origins of our anatomy and physiology, we can think our way through better ways to prevent that kind of illness.”

It is worth remembering, he notes, that we live in the healthiest era ever for the human body and we should be proud of our achievements, especially the past few hundred years of medical science. “Basically, we shouldn't abandon modern life. That said, we are experiencing an epidemiological transition in which more and more people are getting sick from long-term chronic diseases that used to be rare. We evolved, over millions of years, bodies that are adapted for a particular lifestyle, and we get sick from diseases that are what we call mismatched diseases, which are caused by our bodies being inadequately or poorly adapted to the environments in which we now live. Of course, we treat those mismatched diseases by focusing on their symptoms, rather than their causes, perpetuating a vicious cycle, causing what I call dysevolution.”

Take osteoporosis, for example, which currently affects more than a third of women and one in five men in the UK during their lifetimes. This is a perfect example of “dysevolution” and, quite simply, is caused by the decline in physical activity necessary to build and maintain enough bone mass to last a lifetime. “We have skeletons that require exercise and physical activity to grow properly. That's an ancient aspect of our biology that we're not going to be able to change,” explains Lieberman. “We can't develop bone after we mature, so people achieve peak bone mass sometime between the age of 20 and 30, and the more active you are when you're young, the more bone mass you accrue in your body. Then we all start losing bone, that's just life. The rate at which you lose bone is accelerated by physical inactivity because you need to use your bones to keep them, just like you need to use your muscles to keep them. If you don't do enough physical activity when you're young, you won't develop enough bone mass to sustain your skeleton for a long and healthy life. And then we remain inactive as we age, and we lose that bone faster than we otherwise would do so, leading to osteoporosis.”

Because we have not figured out a way to increase bone mass, by the time someone is diagnosed with osteoporosis, it's too late and the disease needs to be managed. But it is, on the whole, preventable. “I'm not arguing that we shouldn't treat the disease,” adds Lieberman. “But we should also look at evolution because that tells us what to do: increase physical activity, especially in children.”

Quite often, this shift from infectious diseases to chronic ones is seen as “the price of progress”, and many doctors attribute this to advancements in healthcare resulting in an ageing population. But Lieberman insists that this doesn't need to be the case. Similarly, the rise in allergies is often connected to the increased use and advancements of antibiotics.

“Your immune system evolved to protect you from all those germs in the outside world, and we still have the same immune system; we didn't suddenly turn off our immune system after we invented sanitation, toilets and antibiotics. They're still there, primed and ready in your body looking for invaders to attack. But now we live in an environment where we remove many of those invaders.

“The decline in demand of the immune system causes it to sometimes behave inappropriately and attack cells or seemingly harmless molecules such as the proteins in peanuts or milk or wheat, and the result is an increase in the number of allergies and other immune disease.”

While Lieberman is not opposed to the use of antibiotics and antibacterial sanitation, he does suggest that we should use them wisely. “There's a cost every time you use them; they change your microbiome – all the animals that are inside you. Every time you use an antibiotic, you're nuking your internal environment and that has a cost. It's a reasonable hypothesis – although the evidence is not conclusive – that the rise in allergies and auto-immune diseases is because of the abnormal way in which we now allow our immune systems to function.”

The growing rate of diseases ranging from heart disease to diabetes is worrying, particularly as Lieberman points out that these are diseases virtually unknown among hunter-gatherers. Again, he believes them to be somewhat preventable. The answer? A change in diet and physical exercise.

The problem with physical exercise, Lieberman notes, is that our bodies are adapted to take it easy. “It's not just that walking is good for you because doctors say so, but we have bodies that evolved to be highly active. They weren't doing triathlons and marathons but they were moderately and sensibly active. Now we've removed a lot of that because of machines and various other technologies.

“But it's important to recognise that most hunter-gatherers are on the margin of energy bounds – they had barely enough energy given all the work they do. When they were struggling with food, it was not a good idea for them to go off on a 10 km jog for the hell of it; that's a waste of energy when you could otherwise use on staying healthy and having more offspring [which was the main thing our bodies were evolved to do].

“So we're adapted to take it easy if we can and enjoy comfort. I know I have to coerce myself into doing exercise. If we're going to turn this around we have to figure out methods to a collective action to help each other act in our own best self-interest. Even when our biology conspires against us.”

But what of the future? Lieberman argues that the main factors to consider in averting much of this ill health are our diet and exercise. “Right now, it's a bit gloomy. But it's not all dreadful and miserable. We're all living longer lives; we're doing quite well in many respects, but we also have rising levels of chronic diseases. The United States now spends nearly 20 per cent of gross domestic product on healthcare and other countries are catching up fast.

“That transition that we're currently going through is alarming and costly and means there's a lot of misery out there, particularly as people age. To some extent, it's because people are living longer: we mustn't confuse diseases that occur in old age with diseases that are caused by old age. To a large extent, we can live longer and be healthier at the same time, but that requires us paying attention to how our bodies evolved.

“We're a species that's capable of acting together and I think if we take effective collective action, it won't take much to turn this around,” he continues. “If we just promote a little bit more physical activity, we could completely reverse this trend in healthcare. Physical activity alone could do it. It's the closest thing we have to a magic bullet.”

'The Story of the Human Body: Evolution, Health and Disease', by Daniel Lieberman (Allen Lane, £16.99) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments