Royal College of Art students collaborate with London hospice to 're-style' the experience of death

The pioneering project aims to enhance palliative care for the patients, but also to bring ideas and discussion about a difficult subject to a wider audience. Lauren Razavi considers the remodelling of mortality

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What constitutes a good death? This is the question posed by a pioneering project set up to redesign the end-of-life experience, based at the Royal Trinity Hospice in Clapham, south London. A group of service designers (bear with me) and design students have spent the past eight months investigating the experience of death and dying in Britain, and how it might be improved.

According to census data from the Office for National Statistics, life expectancy, which was 45 years at the beginning of the 20th century, is expected to be almost double that in 2030. Extended lifespans mean that a growing number of people are facing debilitating diseases in old age and, as a result, more are ending their lives in hospitals and hospices than ever before.

Royal Trinity is the country's oldest hospice and a world leader in palliative care. This year it celebrates its 125th anniversary and, having observed the changing demographics of society first-hand over the course of its history, the hospice continues to strive to innovate and evolve to meet the needs of society. To date, its services have been principally focused on caring for those with a life-limiting illness after they have been diagnosed, but a chance encounter between Dallas Pounds, chief executive of Royal Trinity, and Nick de Leon, head of the service design programme at the Royal College of Art, has resulted in the development of a fascinating new project: to rethink the concept of both living and dying, and encourage users to engage with Trinity's services at an earlier stage in their lives. In doing so, the hospice also hopes to initiate a national conversation about end-of-life experiences and take the subject of death to the British high street.

Sarah Ronald is founder and managing director of Edinburgh-based service design company Nile, which has co-ordinated the project on a pro bono basis since it began, and has supported staff to mentor the RCA design students. "The hospice was keen to set itself apart from others but didn't quite know how to do it," she says. "Together [with the RCA and Royal Trinity], we came up with the idea of redesigning their services and exploring this rich and often forgotten subject of the end-of-life experience."

But how can design help to shape the future of death, and what exactly is service design anyway? Service design teams are collaborative and interdisciplinary, with a results-driven emphasis on problem-solving. Examining an obstacle from a designer's perspective affords the opportunity to analyse and solve it systematically, effectively and in a sustainable way. The rapid growth of the UK's service-design industry has seen organisations ranging from the National Health Service to multinational banks using its innovative approach and methodology. The Nile team was in no doubt about the importance of the subject matter, or about dedicating their time and expertise to assist a collaborative project between the next generation of service designers and an institution as highly esteemed as Royal Trinity.

"The end-of-life experience is something everybody has a vested interest in, because we're all impacted by death in one way or another," Ronald says. "Culturally, we spend more time and energy trying to keep people alive, while ignoring the value that we can create for those who are reaching old age or facing terminal illness."

Studies show that just 30 per cent of people have ever talked about their wishes around death, and for those aged 75 years and over – an age group who might be expected to have greater concern about illness and ageing – the figure is still only 45 per cent.

This growing trend was the key reason that De Leon and his RCA students became involved with Trinity. "Death and dying are part of the human condition," he says. "There's not enough debate [in society] or willingness to confront something that really is inevitable for everyone. It surprises me that the hospice movement is not given greater attention. With an ageing population, and considering the nature of the illnesses we will face, we need to find new ways to support people at the end of their lives.

"Public services are often designed in terms of workflow – how transactions move through a process," he continues. "As service designers, we start by designing the experience first and then engineer the process to figure out what kind of service is needed. We're in the business of designing citizen-centric services, to really understand the needs of people receiving them."

This is not the first time that service designers have taken an interest in end-of-life care. Jeni Lennox, one of Nile's service designers who assisted the RCA students in their research, had already completed similar work at Highland Hospice near Inverness. "The focus of that project, as with Royal Trinity, was on how we can change the perception of the hospice from somewhere that you go to die, to instead being a resource to maximise the amount of life you have left, whether that's a couple of years, months or weeks," she explains.

"Both projects have shown that we are able to manage pain and symptoms by examining and treating the person as a whole. Sometimes it's a matter of organising companionship or simply emptying a bin in someone's room – everyone has different needs, and these aren't always met by medication alone," she says.

Ronald Jones, an associate professor at Harvard Business School in the US and a globally acclaimed service designer, has carried out similar work for hospices in Stockholm, Sweden, which helped to inform his contributions to the Royal Trinity project.

"[My work in] Stockholm highlighted that we're not designing things; we're designing time, as is the case with service design generally. Specifically in relation to hospice care, we're designing a very limited amount of time," he says. "Let's be frank: it's scary to be in a hospice environment for those of us who don't see the end of life coming yet. But if you can put aside those fears and discover your role as a designer, physician or nurse, there's a lot of wisdom to learn."

When De Leon approached his students with an invitation to influence the future of death and dying in Britain, he knew that it was a fascinating design challenge, but also felt that it was important to highlight the seriousness and gravity of the subject matter.

"I told them that this would be one of the most challenging projects they'd ever do, and it would confront them with a set of issues in an environment that they may not be prepared for," he says. "But we actually found there was huge interest in examining the end-of-life experience from a design perspective. In the end, we were over-subscribed with students wanting to participate."

Working in groups, the students analysed and identified ways to improve Trinity's service offering. The service-design approach requires a willingness to reimagine anything and everything within an organisation in order to improve internal systems and user experience. The results of an analysis can be anything from a colourful visualisation of how an organisation functions to the invention of a brand new service with a competitive advantage.

For all the designers working at Royal Trinity, the biggest surprise was the benefit of improving simple, everyday patient experiences. Fang-Jui Chang, one of the project's student designers, defined three areas for improvement: palliative care, administration and enjoyment. "Our research showed that most people find it quite difficult to navigate between the support options available," she says. "Our suggestion was to create a digital platform to provide a personal timeline and specific information to patients, based on their individual condition and needs."

From an enjoyment perspective, students explored catering options that better suited patient needs. "When a person is very sick, they aren't able to eat normal food comfortably," says Chang. "So we looked at ways to make meals that were nutritious, enjoyable and tasty, but in an easy-to-eat jelly-like form. Changes that seem small can make a big difference to a patient's experience and happiness."

Entertainment was another development area for the service designers, and Jones emphasises the importance of observation and interaction with patients in understanding and identifying ways to meet their needs effectively.

"The biggest shocker for me was the significance of distraction," Jones says. "We couldn't figure out why patients were constantly gathering around a television to watch game shows. By talking to them, we discovered that the distraction it offered was the source of its appeal. When we realised this, we began exploring options for other forms of distraction and interaction."

It's been eight months since the project began, and the observations so far are remarkable. "Introducing design into this very sensitive area has been an important step towards achieving that wider public conversation we're seeking," Jones says. "And there's another aspect that I didn't initially consider: bringing back wisdom from the lip of death. I'm not saying that people suddenly have majestic revelations – although sometimes they do – but there's an untapped reservoir of wisdom that seems particularly accentuated at the end of life."

For Royal Trinity, the project has been more successful than they ever imagined. "From a hospice specialist's point of view, it was incredibly enlightening that the service-design team created this detailed flow diagram to demonstrate the role of death and dying in our lives," says Pounds. "It enabled us to understand and reconsider the services we provide, as well as to reflect on the trigger points within a lifespan that might lead people to us.

"Our tagline is 'living every moment', and the service designers took this seriously. They considered not only the 'dying' aspect of our services, but the 'living' aspect too."

The decision to open a new centre, Trinity's House, in early 2017, has been the most tangible outcome of the redesign project. Although this centre will cover the same catchment area as the original hospice, it will embrace a different approach, one that aims to expand the presence and role of Royal Trinity within the communities it serves.

The purpose of Trinity's House is to bring the expertise of the Royal Trinity Hospice to a wider audience, such as older people, carers and the families of those near the end of life, as well as to normalise talking about death and dying in a public setting. "We're not planning to offer more beds, as the new centre's purpose is not to provide another inpatient centre," says Pounds. "We're planning instead to be community-facing, to provide outpatient services and to be the go-to place for information, advice and support on all end-of-life matters."

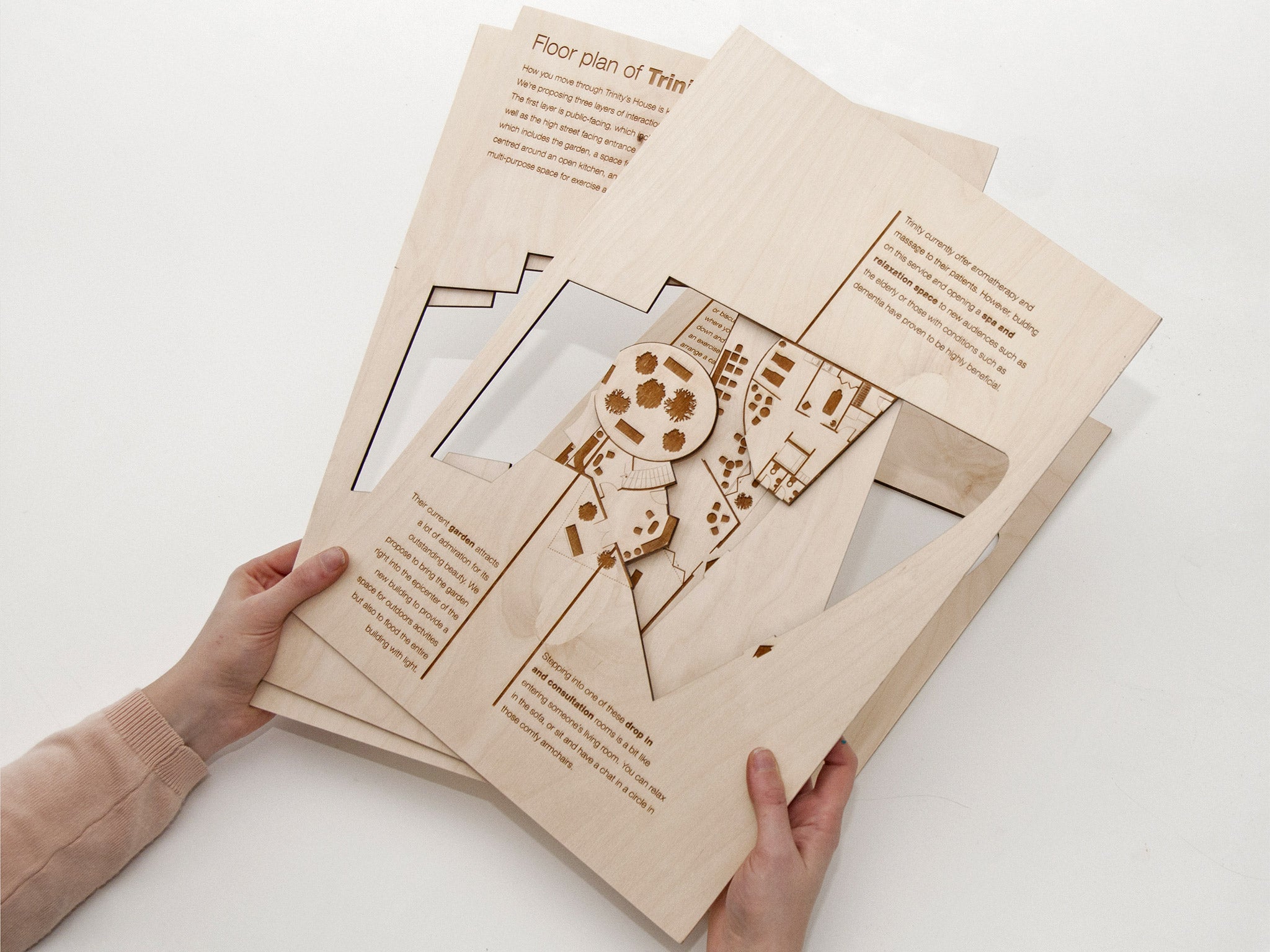

The service designers have proposed that three interaction levels should be reflected in the physical design of Trinity's House. The first layer will be public-facing, allowing anybody to walk in off the street and engage with Trinity's purpose. It will include a café, a multi-purpose events space – for entertainments, or distractions – an open entrance and an information area. The second layer is set to be semi-public with a garden, outdoor seating areas and space for drop-in and one-to-one sessions. The third layer will include an open kitchen and dining area, quiet reflection spaces and facilities for education and exercise.

By separating out services and offering new ones, the service designers believe that Trinity's House has the potential to change perceptions about hospice care and to get people talking about death and dying. "We believe by creating a space for conversations about death and dying that aren't cut off from society, Trinity can help to normalise these issues," says RCA student Lilith Hasbeck, whose group developed proposals for Trinity's House. "The centre will focus on individual need from a new viewpoint and be able to reach a wider cross-section of Trinity's community."

Royal Trinity is still in the process of selecting a building to accommodate their new centre, but the hospice's next steps will be determined by the service designers' findings and recommendations. In terms of selecting the right physical layout, Alison Killing, a Rotterdam-based architect and urban designer who specialises in buildings related to healthcare and death, stresses the importance of architectural design that keeps well-being and human experience in mind.

"Natural daylight, space and greenery – those are clear ways forward for designing spaces such as hospitals and hospices," she says. "Studies have shown that those things have a major impact on recovery times, result in reduced pain perception, and even cause patients to think that the food is better and the nurses and doctors are nicer."

These design factors are often overlooked by the sector because of constraints in terms of budget and practicality. "There are the architectural demands of the bureaucracy to consider: ducts, cables and machinery that must be fitted into the design and kept in certain temperatures and conditions," Killing says. "It can be difficult to strike a balance between the different needs of an institution."

The idea of a separate centre catering to the more human side of end-of-life care, then, seems like a welcome and meaningful progression, one that looks to the needs of the ever-changing present rather than focusing solely on the inevitable finality of the future. It's a fitting testament to Trinity's rich tradition of public service over the past century and a quarter.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments