Profoundly disabled: 'We wouldn't have her any other way'

Rebecca Elliott has become used to the pitying looks her profoundly disabled daughter attracts. But to her parents – and her little brother – Clemmie is perfect

I'm lying next to my little girl, looking into her wide eyes while she smiles that random serene smile, and holds my hand tighter than tight. She is utterly happy; she wants for nothing; she doesn't complain; she's not selfish or jealous or needy: she's just content and perfect and loved. Time like this with Clemmie should be available on the NHS – it is the most glorious therapy.

My five-year-old daughter Clementine is profoundly mentally and physically disabled. Life with Clemmie is, however, not the classic tear-jerking tale of trauma and tragedy through which, as her parents, we plough on because that is our lot. I absolutely love being the parent of a disabled child. Since having Clemmie I've been let in on a little-known secret: profoundly disabled people are awesome.

Believe me I could rant with the best of them about the hardships involved in bringing up a child with a disability – the discrimination, lack of social care, funding, respite and support; and it's incredibly important that these issues are brought to the fore. But these are not negative things about Clemmie – they are negative things about the way our society deals with her. Clemmie herself is not a negative. As with any child, there are ups and downs, good days and not-so-good days, and she has acquired an assortment of health issues. But she is also great company – a pure joy to be around – and very positively touches the hearts of anyone who spends time with her.

Children can see it. They are free from prejudice and have a natural curiosity and acceptance of all things different. This morning, out walking with Clemmie, other children smiled at us, said to their friends, "Did you see that girl?" One girl asked to hold her hand. In contrast, any adults we pass for the most part try desperately not to look our way, stare with frowning faces when they think we cannot see, and, if our eyes happen to meet, give the old teeth-sucking smile – the one that says "I'm so sorry". I appreciate their compassion, but what happens to us that turns our eager childhood acceptance of difference and disability into awkward pity and unease?

In this cynical, meritocratic world we have become fixated with milestone-reaching, SATs testing and parental one-upmanship. We are also taught that success and achievement are the things that gives us our worth, that possessions and measurable accomplishments bring us happiness. Unsurprisingly, if severely disabled children are mentioned at all in mainstream media it is invariably in the context of that bitter-sweet tale of parents coping and ploughing on despite it all. If disabled children ever appear in children's books it is usually in a "conquering all odds" way: "Yes he may be disabled and that's sad but look – little Jimmy's joining in anyway! He's normal after all!" It's the idea that a person's worth depends on their ability to perform in at least one sphere of their lives. Hence television programmes such as Autistic Superstars, featuring enormously talented children with autism displaying their skills. The audience can cope with this, even see it as uplifting, because the children have a saving grace, as it were; they can contribute, they can achieve.

Profoundly disabled people, on the other hand, we don't really know what to make of. There is no achievement, no normality – it's just all too hideously depressing to contemplate. We don't even know how to comfort the poor parents. There's always the classic "Well, you just don't know how much she's aware of – just look at Stephen Hawking!" line – to which I respond, "Stephen Hawking has profound physical disabilities but not mental disabilities. My daughter, on the other hand, was born with catastrophic brain damage with most of her cerebral hemispheres destroyed and replaced with fluid-filled cysts. It's unlikely that she understands much at all." This admittedly unrelenting reply, although said with a smile, often leaves the poor person floundering around desperately trying to think of some other kind of message of hope for our unfortunate family.

Not everyone is so nervous around disability, of course. On that same walk with Clemmie one woman asked what condition my daughter had, stroked her hair and told her she was gorgeous. The woman told me she used to work with disabled children. Ahh, now it's clear – she knows what the others don't; she's in on the secret. She knows that the profoundly disabled can change your life and whole world view not through achievement, not by doing, but just by being.

My husband Matthew and I were just as unaware of this secret five years ago when, after a perfect pregnancy, Clementine was born via an emergency Caesarian at the end of a hellishly long and unfruitful labour, and her limp and silent body was whisked away to the special care baby unit. The following fortnight was a blur; waiting for her to wake up, thinking we were going to lose her, being shipped around from hospital to hospital. Eventually, we brought her home, a bit shell-shocked but overwhelmingly happy that our beautiful little girl had made what seemed to be a miraculous recovery. It soon became clear, however, that she was not developing at all as she should, and at five months old she had an MRI brain scan. The neurologist told us that Clemmie had profound brain damage, and that in fact he had only ever seen one other case this severe in 25 years.

A shocking and heartbreaking discovery, of course, but, after we found out the full extent of Clemmie's disabilities it was easier to come to terms with, and rather than making us love her any less, if anything we loved her more. We started to enjoy Clemmie for who she is, rather than mourn the loss of who she might have been, and I can honestly say we wouldn't have her any other way. She is perfect. She's our fabulous, funny, curly-haired little girl who does nothing and is perfect just because of her uniqueness.

It is this celebration of difference, of life being better because of the existence of children with disabilities, of my little girl being perfect because of her disabilities – not in spite of them – that we so rarely hear about. Scope's marvellous In The Picture campaign was set up to encourage children's picture- book writers and illustrators to include more disabled characters in their work. While this has admirably set the ball rolling in the right direction, it seems that severely mentally and physically disabled children are still almost entirely unrepresented. Part of the reason may be that it is seen as a difficult area to wander into for an author or illustrator who has no first-hand experiences of such disability – there is a fear of offending and a trepidation about entering unknown territory.

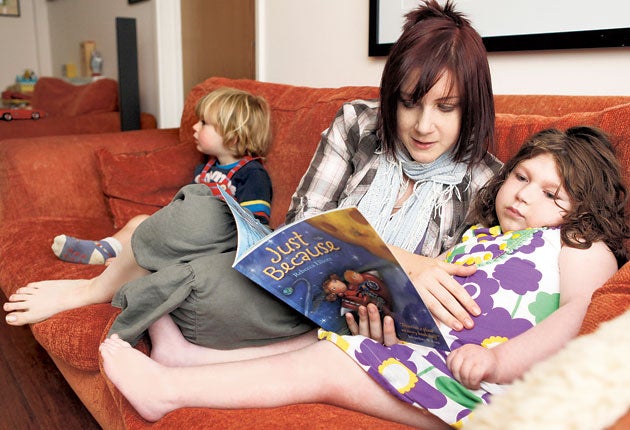

I have been an author/illustrator of children's books for eight years and, having no such fear of offending, set about writing a picture book starring my profoundly disabled little girl. It also features my son Toby, aged two. The way Toby interacts with his big sister is naturally so joyful, so heart-warming, so interesting and so hilarious that the book just wrote itself. It starts "My big sister Clemmie is my best friend – she can't walk, talk, move around much, cook macaroni, pilot a plane, juggle or do algebra. I don't know why she doesn't do these things. Just Because." After that, Toby gives us his reasons why he believes Clemmie is the best sister ever; she's not mean like other sisters can be, she's a lot like a princess as they don't have to do a lot either, just sit and look pretty, she has enormous hair and she has an excellent wheelchair on which they recently travelled to the moon (although they did not visit Jupiter as well, just because).

First and foremost I just wanted to write a great picture book – the kind of book that inspires children to demand "Read it again" at the end – not make some grand political statement. By writing an entirely positive picture book which will perhaps have some effect on opening up the secret, wonderful world of the profoundly disabled to a bigger audience, I also wanted to nurture that unprejudiced acceptance present in all children.

I also didn't write the book to preach some moral message but I think it does subtly convey the idea that our worth is not in doing – in achieving, acquiring and winning, but rather in being. Clemmie proves to me that you don't have to do anything, to achieve anything, indeed to walk, or talk or dance or sing in order to be utterly perfect, enchanting and loved.

Just Because by Rebecca Elliott (Lion Hudson, £5.99). To order this book at the special price of £5.69 (free p&p), go to Independentbooksdirect.co.uk or call 0870 0798897

How to respond to a disabled child

* Don't be scared to look – it's human nature to glance, but don't stand and stare if you feel uncomfortable or shocked.

* Don't be afraid to ask questions. Try to act as you would with any another child. Rather than looking away, pointing, or ignoring a child with disabilities, engage them even if you don't know how they will respond.

* Don't presume the adult with the child is a carer – it's more likely to be the parent.

* Don't feel embarrassed if your child asks questions. In general, children don't understand disabilities. They don't have preconceived ideas about what is considered "normal", and they're unlikely to offend.

* Offer help and open doors. It's really helpful and not patronising to hold a door open for somebody pushing a wheelchair.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks