How to raise a genius

His father calls him a 'young Picasso' and his paintings sell for hundreds of pounds. But is it right to put a 10-year-old's talent in the spotlight? By Rob Sharp

Thick black lines surround a variegated quilt of colour. A lack of conventional perspective makes way for what is known in art circles as "facet-like stereometric" shapes. Then there are the strange, stretched heads, distorted arms and higgledy-piggledy eyes. To the layman the portrait is reminiscent of Pablo Picasso, or at least a reasonable copy. But the canvas belongs to a wholly different kind of prodigy.

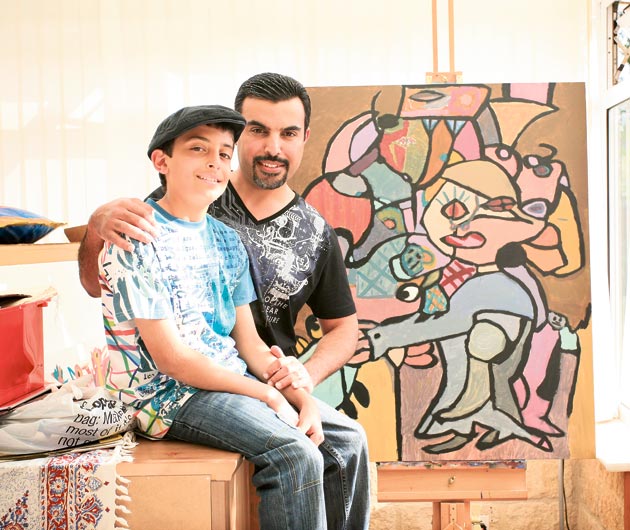

Hamad Al Humaidhan, a 10-year-old Bath resident born in Kuwait, has been dubbed the "Young Picasso" by, well, eager publicists keen to market his talents. But there is no doubting his keen eye, nor the passing resemblance of his work to the Cubist master. Now, Al Humaidhan is selling his work for £650 a go, and is due to exhibit in Liverpool and Llangollen, Wales.

"My Dad told me my painting was like a famous artist," says the 10-year-old over the phone. "I asked him who. He told me it was Picasso. He said he wasn't going to show me any of Picasso's work. He said I had to produce more. So I did, and he brought me an art book and showed me. I'm happy that people have said they like what I do. Now I want to be a professional sculptor or painter when I grow up."

Hamad's situation is typical of children throughout history whose cognitive or creative endowments have thrown them into the public eye. We're all familiar with his Requiem, but what about the ordeal faced by Mozart's parents, Leopold and Anna? From the salons of Salzburg to today's youth-obsessed media climate, the question facing proud mothers and fathers remains the same. Should you let nature take its course or should you nurture your offspring to within an inch of their life?

Hamad's story started in 2006. He tried to reproduce a photograph of footballer Cristiano Ronaldo from a magazine. His father, Walid, a police officer, had moon-lighted as an artist in Kuwait and kept blank canvases at home. Hamad discovered them, put some art equipment lying around to good use, and produced a composition that stunned his father. The boy's technique includes "closing his eyes, seeing an image of a painting in his head, and transferring it to the canvas". If only all art were that simple.

"I told him I liked it," says Walid. "I said, 'Why not make more?'" His father took Hamad's work to a local gallery, then Egypt, then began accompanying him to art shows everywhere he could: Henry Moore, Van Gogh, catching the latest at Tate Britain, running the exhibition gauntlet at the South Bank. Hamad was signed by London art gallery Turner Fine Arts earlier this year and has sold six paintings. His classmates at St Martin's Garden Primary School in Bath have nicknamed him "The Artist" (and are therefore no match for him in the imagination stakes). But for every prodigal success there is a wunderkind quick to fall off the rails. Andrew Halliburton, 23, from Dundee, began studying maths alongside secondary school pupils when he was eight, and was described as "a genius" by the Sun. But the attention made him panic. He now works in McDonald's, and has had trouble holding down the job (he plans to return to university in September).

John Nunn, a 54-year-old chess author and publisher living in Surrey, went to Oxford University at 15. Nowadays, he plays down the genius moniker. "I don't like this child prodigy/genius thing," he explains. "OK, you're a bit ahead of other people in one particular subject, but there is just this spectrum. Human abilities are multifaceted."

So what approach do experts think is best? Do they think Walid is doing the best for his child by encouraging his work and putting him out there? "It really depends on what the child's talent is," says Jack Doyle, a child psychologist based in Glasgow. "If they have a high IQ the chances are they will do well academically in business or in a professional career. Then there are people who are super-gifted in football, or art. But you need to understand that if you're a talented football player it's likely your talent will disappear by the time you're 19." So should parents be afraid of pushing their children to perform? "We all push our kids, to be honest," he continues. "It does no harm. There's more reason to think that very bright children underachieve if they aren't pushed. But you should be wary of pushing them too much. It's a bad idea for them not to have anything in their lives apart from, say, academic achievement, if that's their talent."

In the US, experts advise a more cautious approach. "Our thinking is to encourage the parent to keep a close eye on the child and guide, as opposed to push, them," says Jill Adrian, director of family services at the Davidson Institute for Talent Development in Reno, Nevada, which provides a day school for talented children.

"From our experience, it is the children who are the ones driving everything. They are passionate about a certain topic and they push their parents to give them more opportunity to be exposed to it. Sometimes it is important to be the parent and draw the line if you think opportunities are too much at any one point in time."

Walid seems to give Hamad a mixture of encouragement and advice. "I have read a lot of books on art and keep a lot of them around the house," continues Walid. "I want to make a good atmosphere for him, somewhere where he can work with no pressure. If he wants to go outside on his scooter or play football, then he is free to do it. But I also tell him that he has to invest his time wisely. And he loves it. If I go to London and come back, he might make a surprise piece for me and enjoy that immensely."

That said, while clearly a possessing a precocious aptitude, Hamad shouldn't earmark his space on the wall of the Royal Academy just yet. "In the late 1950s, a French nine-year-old poet emerged, called Minou Drouet," explains The Independent's art critic, Tom Lubbock. "The great litterateur, Jean Cocteau, was invited for an opinion, and delivered his famous judgment: "All children have genius, except for Minou Drouet." It's a brilliant saying. It applies to almost every so-called child genius. Your child's drawings, stuck up on your walls, are – in their own way – very inventive. The "child genius" l ike Hamad, on the other hand, is painfully neither this nor that. True, he has surprising skills for a 10-year-old. But his work isn't like a child's and it isn't like an adult's. It's a kind of fake adult art, a weak and passionless imitation of all sorts of old hat modern art.

"There have been some astonishing early paintings, like Lucian Freud's, but not that early. They were painted in his late teens. The rule is clear. No painter is worth looking at who is still pre-pubescent. As for the exception of Picasso, it's so rare it needn't worry us." Try telling that to Hamad's family. His youngest sibling, four-year-old Worood, is already showing some creative flair with a palette. Suddenly geniuses, like buses, come in two and threes.

Hamad designed a painting to launch this year's celebrations for the 180th anniversary of Covent Garden's Market Building. The artwork was displayed on the Piazza for all to sign with birthday messages. Ukfinearts.com; Coventgardenlondonuk.com

Child prodigies

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Learned to play the harpsichord aged three, and could read and play music by the age of five. Made his performing debut the following year.

Pablo Picasso

One of his best known compositions, 'The Picador', was created in 1889 when he was just eight. He began exhibiting by the age of 15.

Marc Yu

Born with perfect pitch, he made his concert debut on piano and cello aged six. He appeared at the BBC Proms aged nine in 2009.

Sergey Karjakin

A Ukrainian boy who learned to play chess when he was five and became a grandmaster aged 12 in 2002, making him the youngest person ever to have held the title.

March Tian Boedihardjo

A young mathematician born in Hong Kong in 1998, he came to the UK in 2005, gained three A levels at the age of nine and was accepted into Oxford University's PhD programme in 2008.

CHRIS POWERS

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks