How the biological clock is ticking for men as well as women

New studies show sperm becomes less fertile after men reach 35, while the risk of passing on genetic mutations rises. Ana Swanson reports on a thought-provoking threat to male complacency

As a woman goes from her twenties to her thirties to her forties without having children, she's likely to hear more and more people warn her about the risks in waiting to get pregnant.

There are generally well-meaning comments from friends, relatives, even bosses. There are the tearful or fearful advice columns about the danger of waiting too long. There are the pop culture references: Mindy Kaling's ticking clock, Bridget Jones talking about her “sell-by date”, or Ally McBeal hallucinating about the dancing baby. There are the news stories about companies offering egg freezing so women can focus on their careers, rather than their biological egg timers. And what do men hear about having kids as they grow older? Beyond maybe a parent wishing for a grandchild, usually not that much at all.

You might assume that biology explains why women face so much pressure to have kids as they age, but men don't. After 35, the thinking goes, it gets harder for a woman to get pregnant, and, if she does conceive, there's a greater risk the baby will have health problems. According to that thinking, men are mostly untouched by this process, often able to father kids until a ripe old age.

Except it turns out this isn't really true. Researchers are increasingly arguing that men have a biological clock, too, even if most people don't hear it ticking. One of the main people to popularise the idea is Harry Fisch, a New York-based doctor of reproductive medicine who wrote a book called The Male Biological Clock in 2005, which describes how male fertility and testosterone levels tend to decline as a man ages and what can be done about it.

Fisch says a lot of people found the idea that men even have a biological clock to be deeply offensive. “I took so much crap for writing that book, it was unbelievable,” he said. “Holy cow, when it first came out, a lot of people were upset that I was debunking the machismo image of men as they age.”

Yet Fisch and others say the science is clear. As they age, both women and men experience declining fertility, declining hormone levels and increasing risk of health complications for any child – the very combination that most people think of when they talk about a ticking “biological clock”.

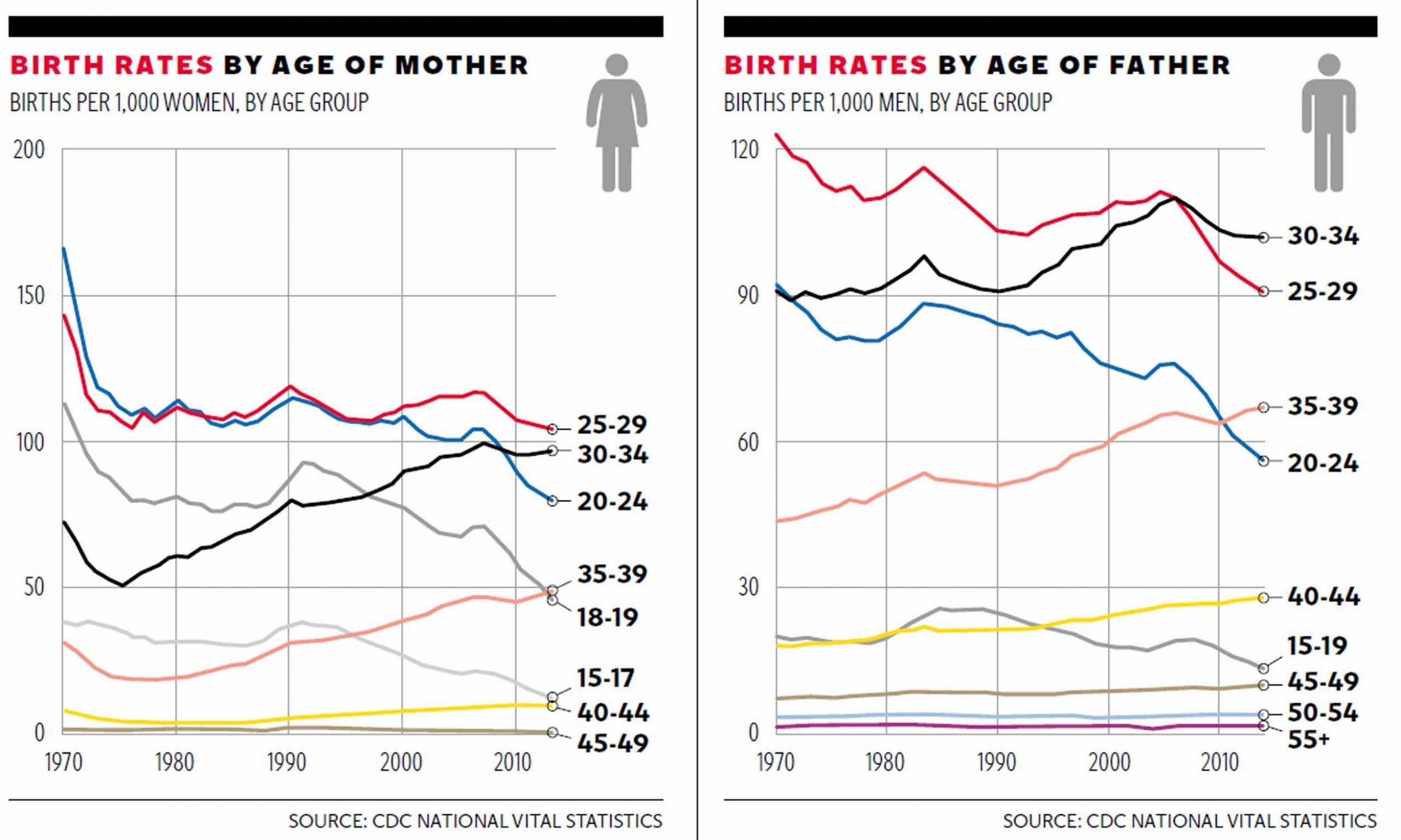

Studies indicate that a man's age can affect his fertility in three main ways. The older the father, the harder it may be for a couple to conceive a baby. Older fathers are also more likely to see pregnancies result in miscarriages. And the older age of the father can also, potentially, trigger health problems in his child.

Unlike women, who are born with a finite number of eggs, men continue to produce sperm throughout their lives, and some can father children into their sixties and beyond – an age when women's clocks have totally stopped ticking. George Lucas, Steve Martin and Rod Stewart all famously fathered children in their late sixties. But for most men, testosterone declines as they age, which can lead to decreased libido and erectile dysfunction. And as they get older, men also see a decline in the quantity and genetic quality of sperm.

“The ageing male, at least from a reproductive perspective, is not as good when he's older as when he's younger,” says Alexander Pastuszak, an assistant professor of urology at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and a specialist in male fertility and reproductive problems. But while these changes mirror similar changes in women, there's one notable difference: most seem to occur a few years later in men, and happen more gradually.

There's a lot of disagreement about when exactly in a man's and a woman's life these changes occur; various studies and experts cite different ages and time periods. But many argue that, for women, fertility declines gradually in the mid- to late-thirties, and then sharply in the forties. For men, the change appears to happen more in their forties and fifties.

One study of 2,000 couples in France found that, while women's reproductive capacity tends to decline around 35, men experience a similar though more gradual decline after the age of 40. Several studies suggest that men over 35 are twice as likely to be infertile as those younger than 25. Another study of about 2,000 couples in the UK showed that, after controlling for a woman's age and other factors, men who were 45 and older took five times longer to conceive than those who were 25 and younger.

Data from the UK study, published in the journal Fertility and Sterility, shows how the advancing age of women and men tends to lengthen the amount of time it takes to get pregnant. For the women and men in their twenties and early thirties, nearly 80 per cent got pregnant within a year. But those rates fell to only 36 per cent for women over 40, and only 25 per cent for men over 50.

Some doctors argue against the term “the male biological clock”, mostly because they don't like the metaphor. Larry Lipshultz, a doctor of urology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, says the term conveys a false sense of finality. “There's just no consensus on when men should be considered of an advanced age reproductively,” he says. “But the concept is certainly one that we should embrace, in that men are not immune to the effects of ageing on their reproductive system.”

For men, some of these changes are treatable or avoidable. Men who are overweight are far more likely to experience low testosterone levels. And male fertility problems are often linked with other health problems, including cancer, hypertension, heart disease or kidney disease, Pastuszak says.

There's also growing evidence that what a man eats, drinks and smokes, what pesticides or industrial chemicals he is exposed to, and even how much stress he experiences in the months leading up to conception can influence the health of his sperm, and thus potentially the health of the baby.

But other changes in a man's reproductive health are just an unavoidable consequence of the march of time. Numerous studies now show that the genetic quality of a man's sperm degrades as he ages, which may lead to infertility, miscarriages, and an increased risk of autism, schizophrenia and certain cancers for the child. This is why the American Society for Reproductive Medicine now recommends that sperm donors “ideally be less than 40 years of age to minimise the potential hazards of ageing”.

The key is that, while women stop producing eggs at a certain age, men form new sperm throughout their lives, with the existing sperm replicating its DNA and then splitting into two, over and over again. That might seem like a fountain of youth for men, but it's actually more like a game of Chinese whispers – each time the process is repeated, there's the chance that the DNA will change a little.

For this reason, it seems, the number of genetic mutations in a man's sperm increase gradually and steadily with age. According to Icelandic researcher Kári Stefánsson, one of the authors of a 2012 study on the subject, the result is that there is a much larger number of genetic conditions that are associated with the age of the father, including early onset cancers, schizophrenia and autism, than with the age of the mother.

Compared with a 20-year-old father, a 40-year-old father brings twice the number of new mutations to a child and is two to three times more likely to conceive a child who will eventually develop schizophrenia or autism, Stefánsson says. But the research shows no connection between the age of the mother and these mutations.

“To me, this was a remarkable observation because, when I was in medical school, we were always warned about the age of the mother,” Stefánsson says. “You could argue that in our work there is buried a little bit of redemption for the old mother that we are always criticising for the risk of having children, because what is truly dangerous is the high age of the father.”

Many experts say these findings should be interpreted with some caution, because scientists still don't really understand how genetic mutations ultimately result in specific conditions, such as schizophrenia and autism. For example, some mutations in the sperm's genes can actually be repaired by the egg before being passed on to the child.

And others, including Stefánsson, say these findings shouldn't dissuade older couples who want to have a child from trying to do so, because the chance of having a child with a genetic disorder is still very low. The study suggests that the chance of having a child with these disorders might double from around 1 per cent to 2 per cent with a man's older age, not a terribly large increase in risk “when you look at it in the context of everything that we have to go through, from the time that we are conceived until we die”, Stefánsson says.

Yet Stefánsson argues that the findings are substantial enough to influence public health, and how people think about paternal age more broadly. “For society, this is very important.”

The disparity between how we think about men's and women's fertility isn't just a matter of science. It also speaks volumes about our assumptions about reproduction, families and gender – and that's one reason why doctors and scientists have put much more time and money into studying women's reproductive health than men's.

Barnes says that, by her calculations, in 2013 there were five reproductive endocrinologists – who mostly treat female patients – for every one urologist specialising in male fertility in the United States. According to Lipshultz, male infertility research is easily a decade behind female infertility research in the US.

This is partially because women's role in reproduction – the cycle of menstruation, pregnancy and delivery – is more immediately obvious than the role that men play. It's also because, for much of human history, giving birth was an incredibly dangerous activity. In the US, about 18 women today die in pregnancy or childbirth for every 100,000 live births, down from about 600 women per 100,000 live births a century ago.

But it's also in part because of deeply entrenched cultural attitudes toward reproduction. Liberty Barnes, a sociologist of medicine and gender, argues there's long been an assumption that fertility, pregnancy and childbirth are women's issues – both in popular imagination and in the medical community.

While women are educated to think about their role in reproduction, men, generally, are not. Until recently, doctors recommended that women go to the gynaecologist every year – providing ample opportunities for women to talk about reproduction with a doctor. Many men, in contrast, don't even know what “the male version of a gynaecologist” is.

Lipshultz says the idea that paternal age affects fertility and pregnancy has not yet filtered out into clinical practice, and that he has never seen a man referred to discuss advanced paternal age. Yet any woman who will be over the age of 35 at the time of delivery will have her medical file stamped with the term “advanced maternal age”, and most will undergo genetic screening for foetal abnormalities. A man's age, in contrast, is almost never considered.

Barnes, who followed dozens of couples for her book Conceiving Masculinity: Male Infertility, Medicine, and Identity, says that couples seeking infertility treatment will often look to the woman first – undergoing treatments like in vitro fertilisation that focus on the woman's body, even though male fertility treatments – such as checking for swollen veins or infections – may be simpler and less invasive.

“As a sociologist, I would say, of course this is linked to gender beliefs,” Barnes says.

Experts say that these findings about paternal age and fertility shouldn't dissuade older couples who want to have a child from trying to do so. However, they could be a consideration for young people who are just thinking about when they want to have families.

“If you're 40 and you're trying to have a child, you do the best you can,” says Fisch, the author of the book on the male biological clock. “But I have a daughter who is 22, and my recommendation to my kids is, why don't you try to have a family early? And that's for both men and women. But I certainly would love it if my kids had kids before they're 30, and that's from a fertility doctor's point of view.”

Alexey Kondrashov, a geneticist at the University of Michigan, agrees. He says the findings about older men and genetic mutations are not enough to discourage older parents from trying to have children. However, they might be enough to encourage young men to freeze their sperm in case they want to have kids later in life. “Eighteen-year-olds don't think about these things, but if I was 18 years old and capable of thinking of things like that, I would think about it carefully,” he says.

As the idea of the paternal biological clock becomes more widespread, it could also be an important guiding principle for how our society functions more broadly – for example, encouraging more doctors to talk to men about their fertility, and turning stressful workplaces into family-friendly ones. It could also be an argument for supportive policies, like paid family leave or child care, that might help men and women have kids at a younger age.

To quote Rene Almeling, a sociologist at Yale University studying medicine and gender: “If we really start to think of reproductive responsibility as something that is not just applicable to women... I think it raises a host of questions about other contentious debates.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks