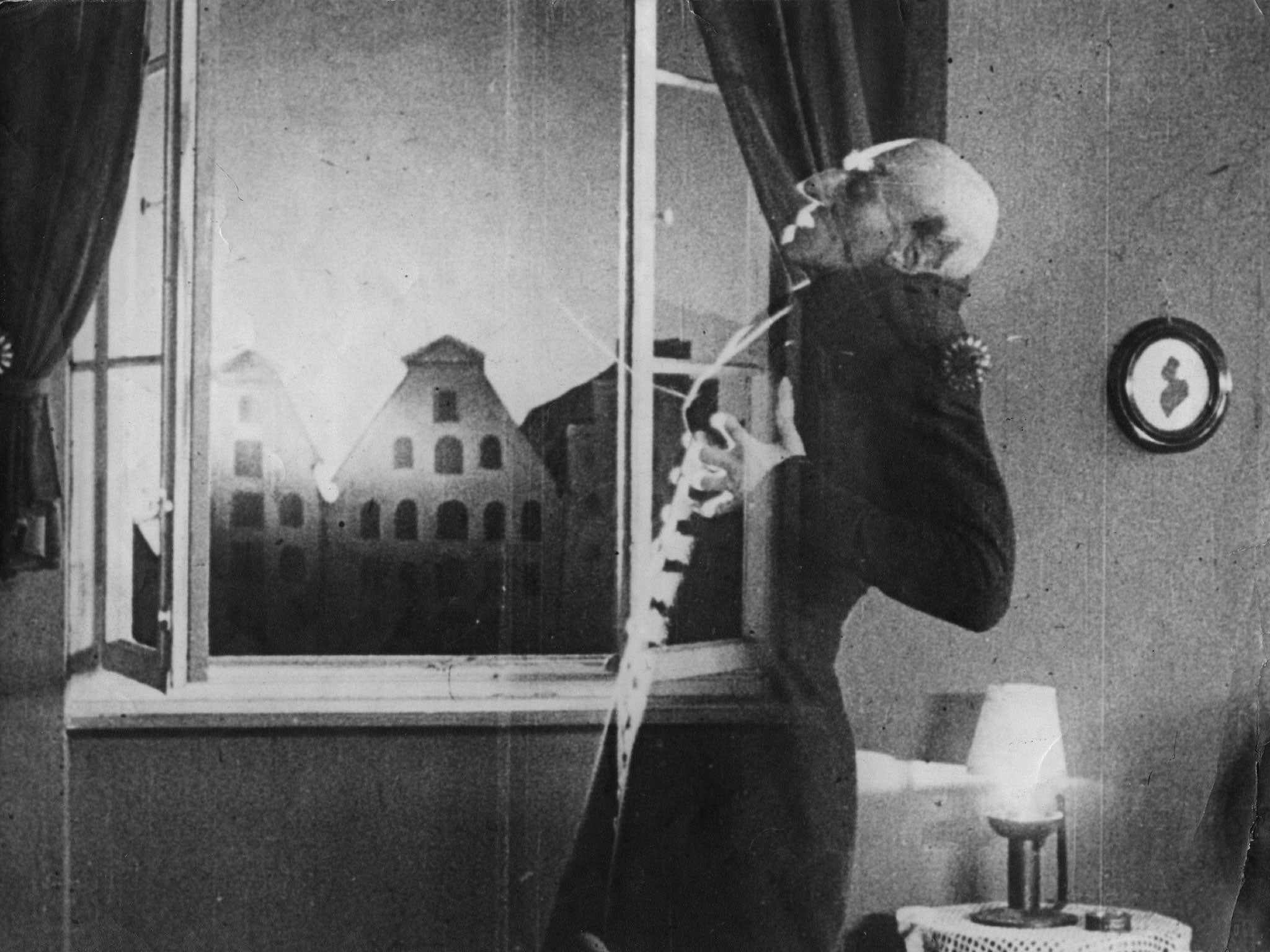

Halloween and horror films: Why do we enjoy being scared?

On paper, nothing about horror films should attract us - so why is it a billion-dollar industry?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The blinds are tightly drawn, the door is (double) locked, and you are armed with a particularly thick blanket ready to cover your eyes and block your ears. You tentatively start the film knowing you won’t be able to sleep for weeks or shower without fearing what might be lurking behind the curtain.

As Halloween approaches, many of us who have outgrown trick-or-treating will watch a horror film - an altogether more bizarre indulgence.

Replete with bloody gore, tales of paranormal beasts and terrorised characters, our brains should arguably be programmed to avoid horror films. So why do millions of people scare themselves for entertainment?

Beneath the caked fake blood and prosthetics, horror films have a soft centre: they have the power to unite us and can boost our confidence. They are also big money-makers, grossing over $8billion worldwide since 1995 (following romantic comedies), according to movie statistics website The Numbers.

“I don’t think you forget your first. It was John Carpenter’s Halloween,” Chris Nials, the founder of The London Horror Society – a horror community – says, recalling his first encounter with the genre aged 11.

Playful peer pressure led him to watch the 1978 classic (without his parents’ knowledge), but the thrill made him a die-hard fan of the genre.

“I was pretty gripped from the outset. Although I was incredibly nervous before watching it.”

“The buzz that I still get when watching a new film is still there. To me, being frightened in a controlled way is almost like an extreme sport or roller coaster ride.”

“I think it’s the same feeling as anyone gets when they get to see, watch or hear a piece of art that they’re particularly into. For me, I get the biggest kick out of watching a film that affects me emotionally and is loaded with twists and surprises. I like to leave the cinema or sofa still thinking about what I’ve just seen for hours on end!”

This attraction to controlled fear is the key to the appeal of horror, and one which the genre shares with adrenaline-fuelled pursuits like extreme sports.

When a person is afraid, the amygdala, an almond-shaped set of neurons in the brain, triggers the “fight or flight” response, causing palms to sweat, pupils to dilate, and ensures that the body is pumped with dopamine and adrenaline.

Our bodies respond to both genuine and fabricated fear in this way, but feelings of pleasure rely on the invidual and whether a person subonsciously knows they are safe.

A recent study by Dr David Zald, Professor of Psychology at Vanderbilt University in the US, showed that some people’s brains lack what he called the “brakes” on dopamine release – meaning they're more attracted to being scared.

"Fear and pleasure are very closely related. The same physiological reactions occur in both cases, and in fact using a polygraoh machine to measure heart rate, pupillary dilation, electrical skin conductance, breathing rate, and other physiological activities will not really tell you whether a persons is afraid or excited," explains Dr Bryan Roche, Lecturer in Psychology, Maynooth University, Ireland.

"For some people the experience of watching a horror film creates physiological feelings that are always interpreted as "fun", "a short thrill" and so on. But for others, the feelings in their bodies are interpreted as "terror" or other similarly negative states."

And taking advantage of this sensation is not a modern phenomenon. "Self-scaring" has long been a way to unite people, giving them a sense of belonging and boosting feelings of power, says Margee Kerr, a sociologist who specialises in fear.

"We’ve been scaring ourselves forever—from scary stories around the campfire to jumping off cliffs, to sledding down hills, we’ve always chased the thrill."

For example, rollercoasters may seem like a twentieth-century invention, but they were in fact inspired by 17th century Russian ice slides, where riders would speed down slopes on toboggans at high speeds.

"For others being scared in a safe place is a source of enjoyment and makes them feel good physically and can even serve as a confidence boost by reminding us that we can make it through a scary situation, we are strong," Dr Kerr adds.

Watching a horror film is also arguably "part of our cultural and genetic inheritence", says Dr Roche.

"Humans enjoy intense emotional experiences in groups. People go to rock concerts, to the Vatican to hear the Pope speak, to Royal Family events, and so on, to experience a sense of connectedness with others and to share intense emotions, even with strangers."

And those worried that their penchant for horror is a symptom of an underlying issue, experts stress there is no evidence for this – but you’re certainly not alone if you feel unsettled after watching a horror film.

“Certainly, if an individual became obsessed with gruesome images and horrific scenarios it could indicate some significant psychological problems," says Professor Glenn Sparks of The Brian Lamb School of Communication.

“But, overall, a more damaging effect may be what we refer to as lingering emotional disturbances that people may have after seeing something particularly upsetting.

“My research has shown that sometimes the disturbances last for weeks, months, or even years.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments