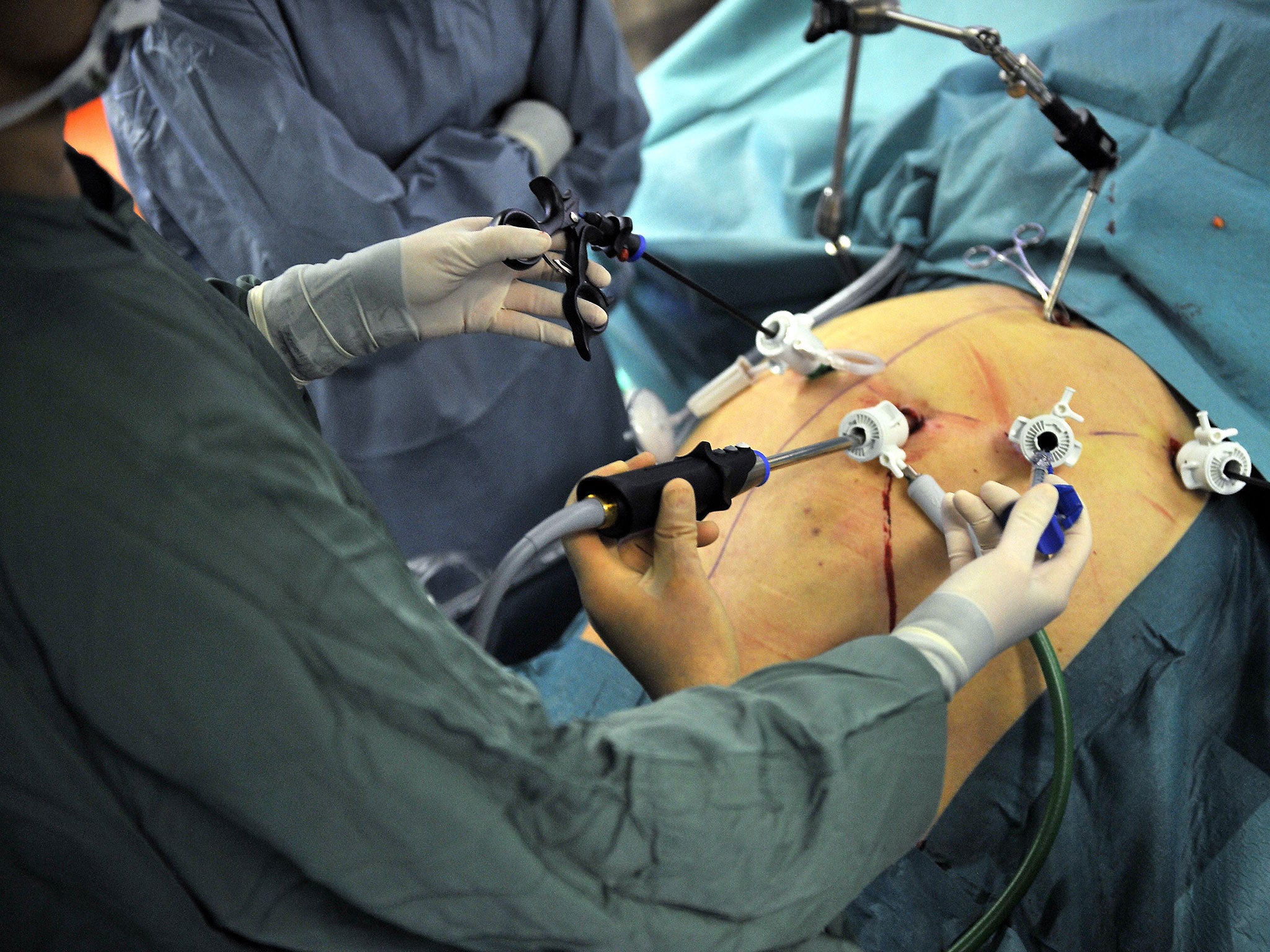

Gastric surgery: Is it really the answer to the UK's obesity epidemic?

Nice says it works, but critics argue that it’s crazy to operate on healthy people just to stop them eating

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When 38-year old Jess Palmer hit 18 stone earlier this year, she decided that it was finally time to go under the surgeon’s knife. After a lifetime of struggling with her weight and trying every diet imaginable, she was still putting on a stone each year. Things got worse after she had two children and in June, when her body mass index (BMI) reached 41, placing her in the category of the morbidly obese, she signed up for a gastric band.

Palmer, from Cardiff, had grown up with a mother who was constantly dieting and counting calories, and a large part of her decision to get a gastric band was based upon not wanting to pass her own bad habits on to her children. "I was determined to break the cycle," she says. "I want them to be in an environment where food is used for fuel and enjoyment not for rewards or punishment."

Palmer dutifully went on the pre-op diet (most surgeons insist that their patients go on a two- to six-week diet beforehand) on which for a month she ate nothing but liquids and shakes. She lost a stone. "They place the band right at the top of the stomach, just underneath the receptors that tell your brain you are full," she says. "I do get hungry now, but not anywhere near as much as I did before. Since having it, I’ve lost three stone."

While the recovery from the operation was fairly straightforward, working out what foods to eat wasn’t. "I had to learn to eat in a totally different way," Palmer says. "I’ve been trying to follow the 20, 20, 20 rule, which is to take 20 chews, leave 20 seconds between each mouthful and take 20 minutes to eat your meal. It’s very difficult to do, particularly when I’m also trying to feed young children.

"Also, if you eat something that’s slightly too big, suddenly you get all of this stuff backed up in your oesophagus and there’s only one way it can come out. And sometimes it doesn’t come up, and that’s pretty grim because you have to try and bring it up. It’s not sick, because it hasn’t been digested, it’s just stuff that’s stuck above the band, like a bottleneck. Sometimes, when things got stuck, it felt like I had a knife in my chest."

Last month, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (Nice) revised its guidelines and said that we should be offering more of this sort of gastric surgery to people on the NHS. Previously, patients had to have a BMI of more than 35 to be eligible. Now, Nice is suggesting that this figure be reduced to 30. According to Nice, 6,500 of these procedures were performed last year. If its recommendation is taken up, that figure will nearly double.

How ludicrous, say its detractors, that we should be offering expensive, invasive surgery to overweight people on the NHS. How crazy that we should be removing half a healthy stomach at a cost of around £7,000 or tying it up with band for £2,000.

"You may as well put a plaster on a severed artery," Zoe Harcombe, author of The Obesity Epidemic, wrote in The Independent on Sunday. She is a campaigner who believes that dietary advice is too closely tied up with food corporations and is making us fat. "This is not going to stop the problem," she says. "It shows no understanding of the problem."

But the problem is that we are living through an epidemic of obesity. In this country, 64 per cent of adults are classed as being overweight or obese. We’re not so far behind America now, where the proportion is around 75 per cent. And this is fuelling a massive rise in type 2 diabetes, the fallout of which includes heart disease, stroke, blindness, kidney failure and limb amputations, and currently costs the NHS 10 per cent of its entire budget. Put one way, we simply can’t afford to have a population this fat. "I fully agree that we’ve got to do the preventative stuff first, but we’ve also urgently got to do something to stop this from happening," Shaw Somers, a bariatric specialist at Portsmouth Hospital, says. "It’s stupid, me operating on a perfectly normal digestive system just to stop people eating. It’s nonsense. But unfortunately, it’s the only thing that works for those people who are already past the point of no return. Now, there are more than two million of them and counting. And every year that goes by, there are more."

The types of operation that Nice is suggesting include the gastric sleeve, in which about four-fifths of the stomach is removed, leaving the remaining piece stiff like a hose-pipe, so that afterwards, the patient is unable to eat much more food than would fit into a banana. Then there’s the band, Palmer’s choice, for those who don’t want such a complex operation. This works like a width restrictor in the road, narrowing the top of the stomach to slow things down. And, most complex of all, there’s the gastric bypass, which involves dividing the stomach into two, and connecting both parts to the small intestine, effectively reducing the size of the stomach by about 90 per cent. Which operation suits which patient depends on many factors, but generally a bypass will be for those who need to lose the most weight, followed by a sleeve and then a band.

Mr Pratik Sufi, Consultant Bariatric Surgeon at Spire Bushey Hospital, thinks that the Nice recommendations are long overdue. Currently, Britain lags far behind much of Europe and America in its attitude to gastric surgery. Dr Sufi likens it to paying a mortgage instead of rent, in that there would be a big initial outlay over the next two or three years, but a much bigger saving in terms of diabetic care in the long term. He thinks that our reservations are down to preconceptions about overweight people.

"There is a prejudice in this society that fat people are fat because of their lifestyle," he says. "When someone has an accident, say from skiing, we don’t say they shouldn’t be treated because it’s a lifestyle choice. But when it comes to obese people, we deal with them differently. People think that it’s all to do with lack of willpower. That’s simply not the case. It’s a very well-established fact that once you have reached a certain weight, the body resets itself to make that its target weight, and so will always try to put you back to that weight.

"Diet and exercise works temporarily, but within two years, virtually everyone puts the weight back on again. You would not be able to show me one single study that suggests otherwise. There isn’t one. Evidence shows that once you have crossed a BMI of 30 to 35, the most effective way to lose weight and keep it off is these sort of operations."

And as Palmer testifies, gastric surgery certainly isn’t the easy way out. After struggling to keep down many foods, she realised that her band was a little too tight. She went back for a "fill", where the amount of saline solution in the band is adjusted through a small permanent "port" in her stomach to make it sit tighter or looser. At one stage, the band was so tight that she couldn’t even fit her Wellwoman vitamins through it, so she began to get ill a lot, too.

"At first, my weight just plateaued," she says. "It was quite disappointing and also really embarrassing that I’d had this huge procedure and I wasn’t even losing much weight."

Now, Palmer thinks that she has got the hang of it and generally has a diet of muesli for breakfast, salad for lunch and vegetables and fish in the evening. "I thought you just get the band fitted, you don’t eat and the work is done," she says. "But it doesn’t work like that at all. You have to be very careful and you definitely have to work with your band. People don’t realise that it isn’t a simple option."

These days, people can go and have a gastric band fitted in the morning and be out that same afternoon. After a bypass, they’re usually home within two days of the surgery. It wasn’t always this way.

The bypass was invented in 1965 by an American doctor, Edward Mason, "the father of obesity surgery", and was a tricky, complicated operation used only as a very last resort. "Some of the intestinal bypasses of the 1960s were devised to short-circuit the entire digestive system so that food goes from mouth to anus in about 20 minutes," Shaw Somers says. "But they fell out of favour. It really worked for weight loss, but patients start dying of liver failure and nutritional deficiencies."

In the 1980s, the gastric band was introduced, but it wasn’t widely used because it was still a major operation, as a large incision had to be cut across the abdomen. It was only with the invention of keyhole surgery in the late 1990s that gastric surgery was revolutionised.

"Before keyhole surgery, bariatric surgery was a big deal and was really only reserved for those enormous patients whose life was about to end if we didn’t help them," says Somers, who has been practising since the very early days and has now performed around 3,000 operations. "I’ve watched it over the years develop into a very safe, very effective treatment."

At the beginning of the 2000s, gastric banding really took off, and became far and away the most popular procedure. "It captured the public’s imagination because it was safe, adjustable and reversible," Somers says. More recently, the bypass and the sleeve have become the more common choices.

Sue Smith, 55, opted for a bypass when she was told that she probably had about three to five years left to live. She had ballooned to 26st after a bad car accident reduced her mobility. "I had tried everything," she says. "I must have lost the same three stone 10 times over. Surgery is not a quick fix – you have to completely change your lifestyle. But I’m now able to work and I have the same life expectancy as anyone else now. I do think it should be more widely available on the NHS."

Dr Sue Jackson, a teaching fellow at the University of Surrey, is studying the psychological impact of gastric surgery and believes it isn’t something that should be widely offered until we have much better screening of patients. Currently, screening is not standardised. When Palmer went for her surgery, for example (she went privately), no questions were asked about the possible reasons behind her overeating.

"If someone has been banded and they then go and binge eat, they are potentially putting their lives at risk," Jackson says.

"We need to screen those people out and, currently, there is no system for doing that. Some people eat as an instant reward because it makes them feel better. When they have that taken away, what else do they do? We’ve seen instances of people taking up drinking, smoking and other completely undesirable behaviour. The problem is, these types of surgery definitely don’t suit everyone."

And she’s right. There are forums and self-help groups whose message boards are filled with tips on how to "cheat" the band. There’s nothing to stop you liquidising a Mars bar, downing fizzy drinks or, as Palmer did initially, bingeing on cream cheese, chips and dips.

"Usually, people have a psychological reason why they are morbidly obese," says Palmer. "It’s obvious that there are emotional reasons behind my weight problem, I just don’t know what they are. My doctor said that once you lose weight, these issues are resolved, it’s all a matter of confidence. I think that’s bullshit. It’s treating the symptom and not the cause."

There’s another big question mark over the long-term implications. Many NHS trusts will only pay to have two or three follow-ups, but European guidelines say that patients who have had gastric surgery should be subject to a lifetime of monitoring. Also, questions remain about how long the surgery itself will last. The problem with the bypass and the sleeve is that, after five years, the stomach stretches again and things can start drifting back to the way they were.

Paul O’Brien, a Melbourne-based professor who introduced the gastric band to Australia in 1994, has done one of the few studies looking at long-term results and he found that after 10 years, people who had had a bypass or a sleeve were actually slowly regaining weight, while those with a band, because these can be adjusted, were more stable.

An analysis of British results shows that, despite the bypass being initially more successful than the band or the sleeve, with patients losing around 70 per cent of their excess weight, three years later, all patients were heading towards 50 per cent excess weight-loss.

"It’s a fallacy that these operations are permanent and they work for ever," Somers says. "Because over time, the operation fades and becomes tired and your body’s natural mechanism starts to work again. Our bodies have a great propensity for figuring out what we’ve done to them surgically and reversing that. None of these operations is going to make you normal."

But all this could be immaterial because Simon Stevens, chief executive of NHS England, has already indicated that he is probably not going to take Nice up on its recommendations. He would rather put money into prevention than surgery.

"Unfortunately, we know that prevention for obesity does not work," concludes Somers. "Surgery may not be a panacea, but it’s the only thing we’ve got. Until the Government gets its act together and gets to grips with the food industry and stops the gratuitous advertising of high-calorie stuff, this is the way it will be. Obesity is a chronic relapsing illness. I would love to hang up my scalpel, but right now, that’s just not going to happen."

Jess Palmer blogs at http://mrshelicoptersgastricband.blogspot.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments