Father's Day, my old dad, and Alan Stoob: Senior citizens have a lot to offer

When Saul Wordsworth was born, his father was almost 60 – but you would not have known it. As Father's Day nears, the writer remembers the man who most inspired him

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Elderly heroes in fiction are few and far between: Miss Marple, Hercule Poirot and Rip Van Winkle all spring to mind, but they are very much in the minority compared with the youthful exuberance of most chief protagonists. It seems reading glasses, leisurely lunches and advanced Sudoku skills are rarely prerequisites for such a role.

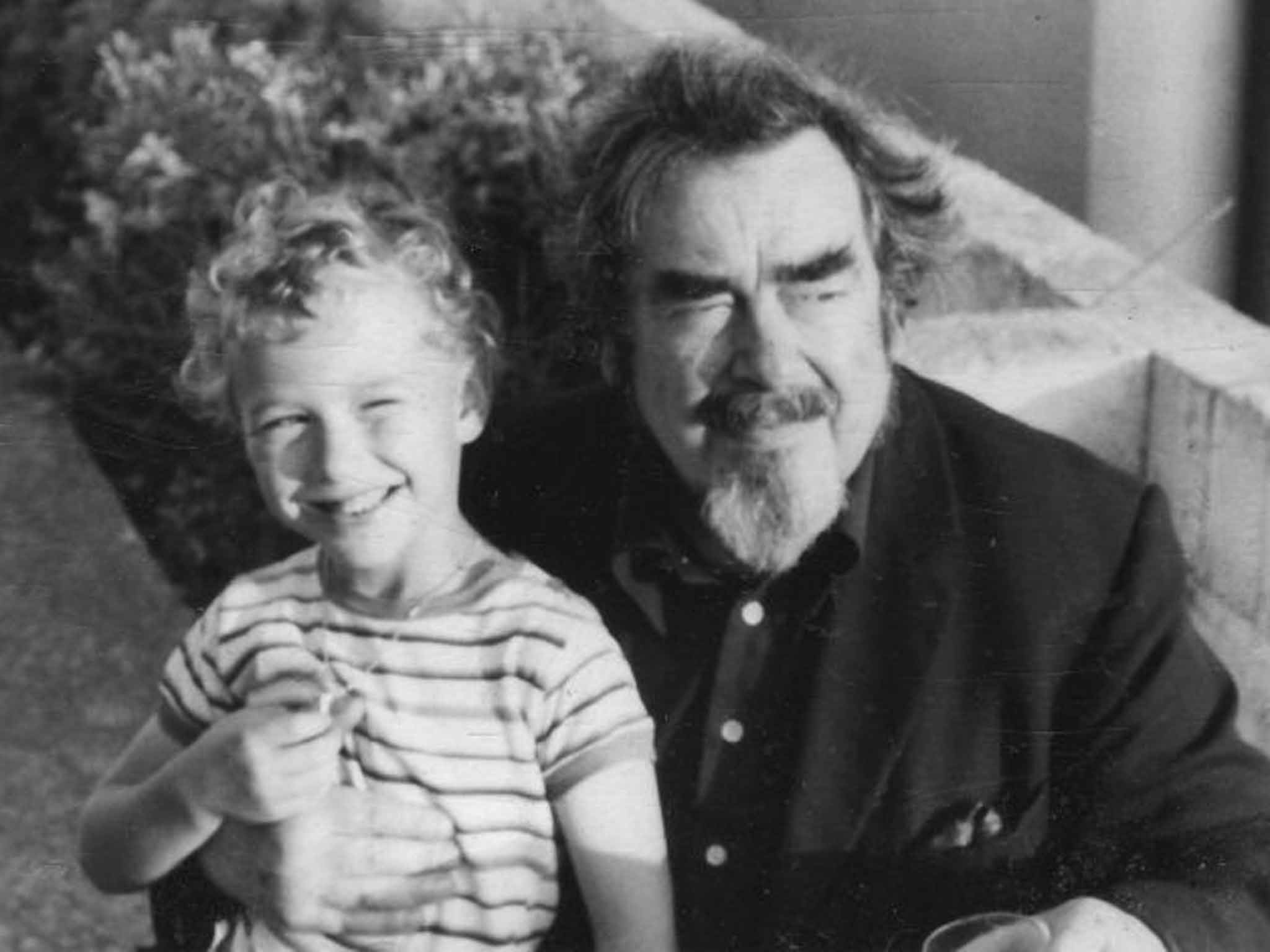

I have always been surrounded by older male role models. When I was born, my father was 59. Last year was the 100th anniversary of his birth. There are not many 42-year-olds who can say that, or remark casually that they have a half-sister who is 83 (or a half-brother of 73). Growing up, I was constantly aware of my father's age. My party piece in the playground, rather shamefully, was to reveal how old my dad was to other children. "You've got it wrong," they'd say. "Miss, Saul is lying again!" When I was 11, my rugby teacher claimed he'd bumped into my grandfather on a train to Twickenham. "My grandfather, sir?" I said. "He's not really a rugby man." Half an hour later, it dawned on me that he meant my father. As a means of exaggerating his age, Dad would always remark that he was "in my 80th year" rather than admit to being a mere 79.

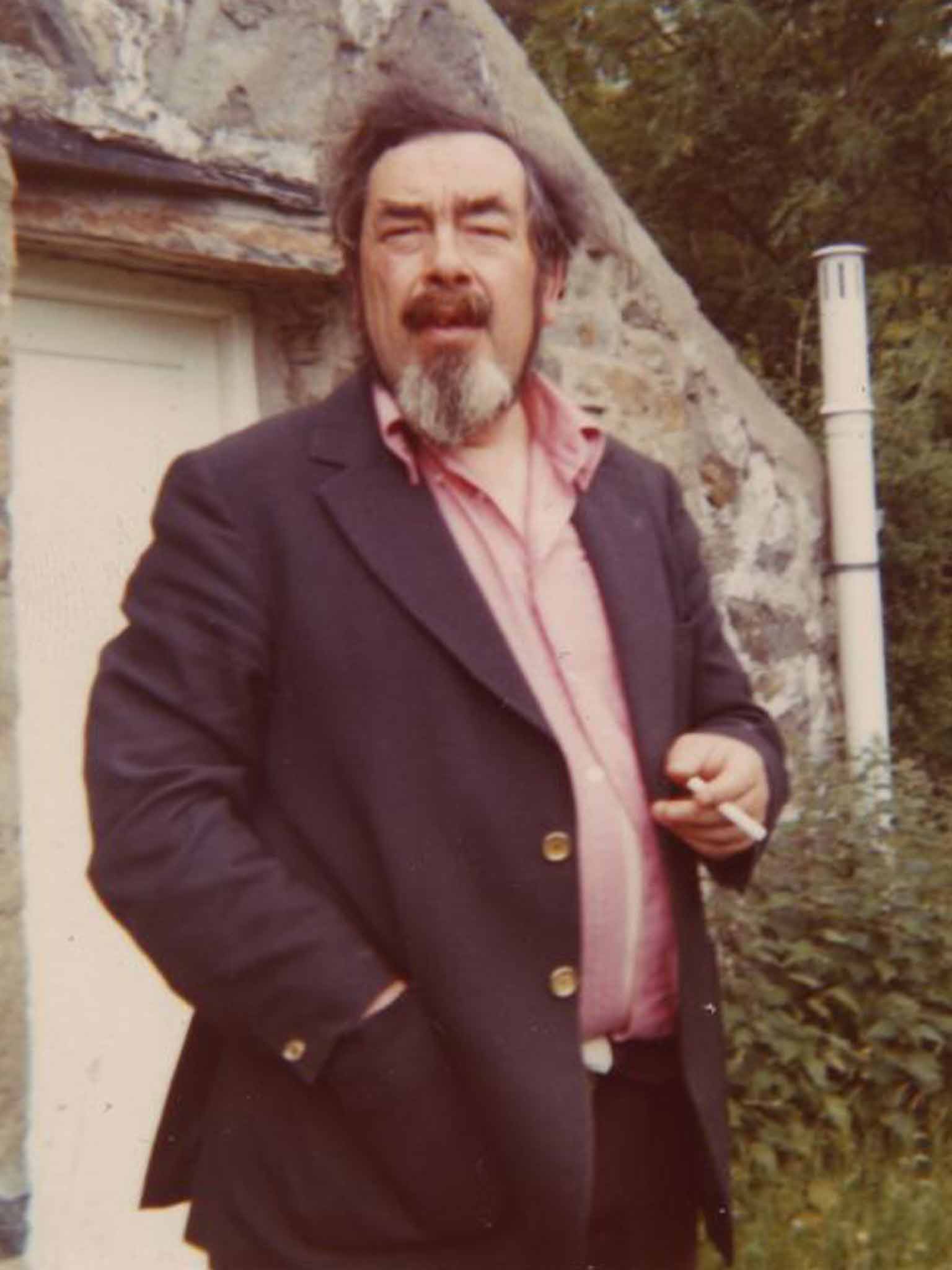

There are a number of reasons for my late appearance, the principal one being my mother, 20 years my father's junior. That he met her so late in life is due to his own messy life and late reinvention. He was born in Calcutta in 1914, got sent down from Oxford, blew an inheritance, married, went to war, divorced and found himself washed up on the shores of North Wales. For a time, he lived with the former wife of John Russell, Bertrand Russell's son, before she developed schizophrenia. Eventually, aged nearly 50, he found his way back to London and began reviewing books and reporting on sport for the broadsheets.

I find myself constantly revisiting my father in my writing, understanding him better as I go. Perhaps his colourful traits were always going to end up shaping my page. Alan Stoob, the elderly and eponymous hero of my novel, is an amalgamation of both him and my grandfather, with a little of me thrown in. He suffers from many of the problems associated with old age: arthritis, asthma, back trouble and (ahem) erectile dysfunction. But he also has a youthful energy that is increasingly in keeping with the older generation. Like my father, he snoozes most afternoons and never tires of reminding people how old he is. Like my grandfather, he has a hot Ribena and a sliced apple for elevenses. He also suffers from anxiety – a result of being evacuated during the war – and along with a host of other medication takes antidepressants and sees a therapist. We all know that a lifetime isn't always long enough to solve our problems, but Alan remains a hero. As Britain's Premier Nazi Hunter™, how could he not?

Despite his advancing years, my father never behaved in an elderly manner. My maternal grandfather, eight years his senior and half a mile down the road from us in Harpenden, seemed ancient by comparison. Dad had a full head of hair, a ready wit and a booming voice. Despite his age, he was still able to throw a ball at me in the garden or take me to London for day trips. His body gave out on him briefly in 1982 when, aged 68, he suffered a heart attack, but he lost some much-needed weight and bounded on for a further 14 years – remarkable considering drinking, smoking and not walking anywhere were three of his favourite pastimes.

All those years in the wilderness had apparently preserved his energies. He would often stay up for two nights on the bounce writing his copy. Of course, by now he had to provide for a wife and a young child. Four children preceded me, but it was only me he truly raised. This pained him (and later embarrassed me). It would certainly explain those dark moments alone in a chair. Sometimes, I would ask what was the matter. He would allude to a misspent youth and some unfortunate choices before, head in hands, lamenting "the years that the locusts have eaten".

As I entered my twenties and he his eighties there was an increasing poignancy to our meetings. Would this be our last dinner, our last Pimm's, a final embrace? In the end, he made it to 83, having gone on working until the last, squeezing out every last drop that life could offer.

When I think of him now, 17 years since his death, I recall the liver spots on the backs of his hands, the thud of review copies hitting the floor as he dozed off after lunch, his huge physical strength – he would still try to compete with me well into his eighties – a ferocious temper, but also a great tenderness. A complex life made for a complex man but the years knocked the edges off him. Mostly, there remain his famous witticisms – it was he who coined the phrase "legend in his own lunchtime" – along with endless anecdotes told and retold. One of my favourites – and brace yourselves – is of my mum missing her pudding bowl and firing squirty cream across the dinner table. "I wish I could do that," he deadpanned. My teenage self squirmed.

Not only is the character of Alan Stoob based in part on my dad, but it was he who instilled in me an early obsession with Nazis. When I was a child, he announced one day that Hitler was alive and well. This may have been for his own amusement (har har) or simply because he loved to myth-make. As a result, I came to believe that Duncan Price's father – who walked past our house to and from work every day – was the Führer. He certainly had the moustache. A lifelong obsession was born, one that has now spawned a novel and – with a bit of luck – a Hollywood film.

What my father would make of the book is hard to say. He would most likely have been unbearably proud, with a residue of jealousy. He spent his life threatening to write one himself. "Good luck with the book, Mr Wordsworth," was a familiar refrain uttered as he clambered out of taxis or exited shops, having no doubt spoken of the novel he was writing – a novel that no one ever saw. Now, I am hearing the self-same phrase. Frankly, it's freaky.

Championing the older generation is timely. We are constantly told that 50 is the new 40, 60 is the new 50, and so on. It wouldn't surprise me if we saw a surge in aged literary heroes. Senior citizens have a lot to offer. I should know, my dad was one.

'Alan Stoob: Nazi Hunter' by Saul Wordsworth is published by Hodder & Stoughton (£8.99). Follow Alan Stoob on Twitter @nazihunteralan.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments