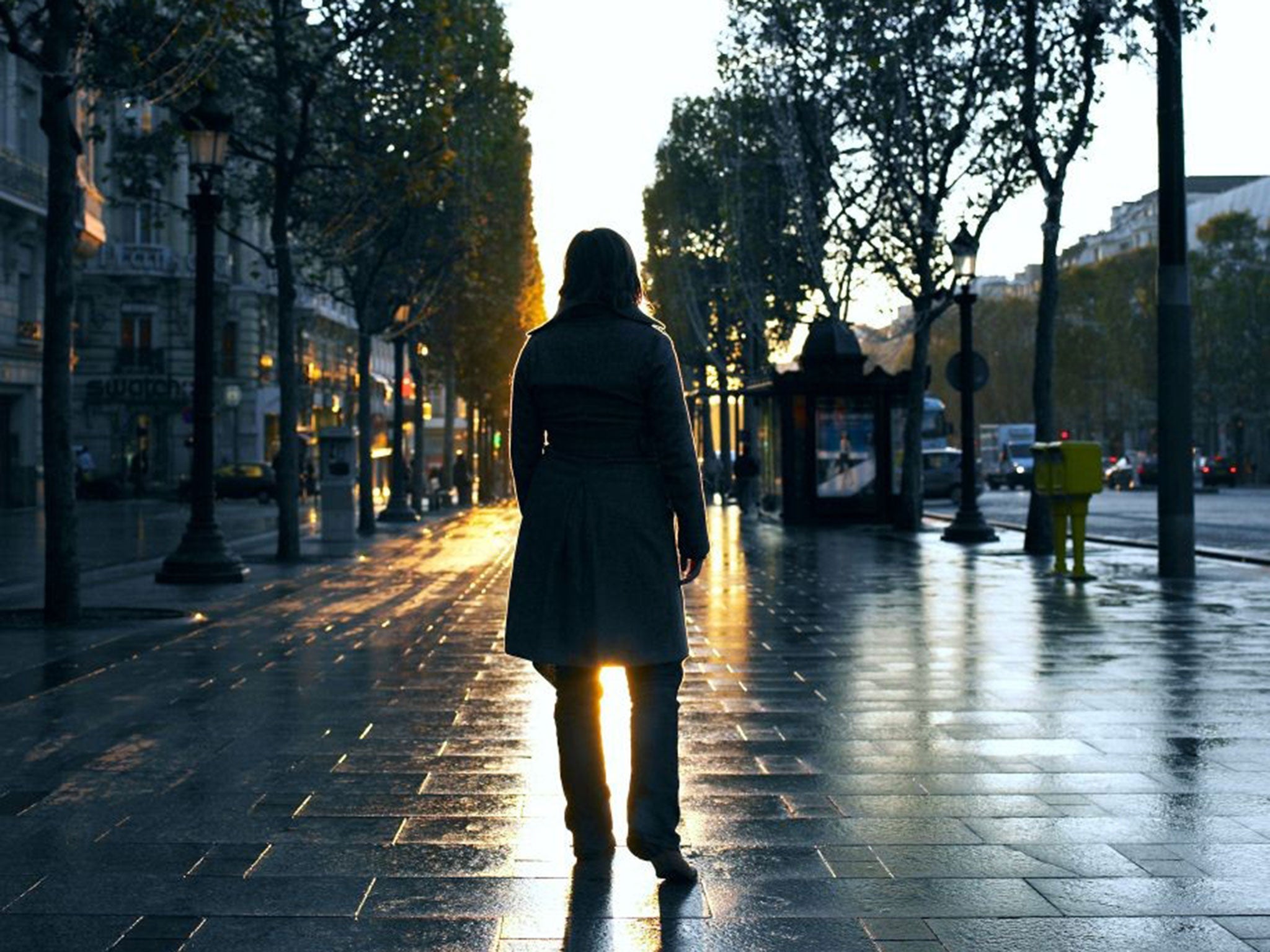

Britain has been voted the loneliness capital of Europe - so how did we become so isolated?

Not only can loneliness lead to mental-health issues but studies proved that it can also be more dangerous than obesity and smoking

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Every Tuesday at 6pm, Caroline, a 78-year-old widow, settles down in a comfortable chair in the hallway of her north London home and waits for a phone call. Wilma never fails to ring right on time. The pair then chat away for the best part of an hour about everything from their families, to football scores, to the situation in Ukraine.

When I visit just before this week's ritual call, Caroline speaks warmly of Wilma, beaming when she recalls one of their recent conversations. It would be easy to draw the conclusion that Wilma is an old neighbour, or a dear cousin, and not, as she is in fact, a woman who lives more than 200 miles away and whom Caroline has never met.

Wilma is a volunteer for The Silver Line, a charity that offers friendship for lonely elderly people. As well as a 24-hour free helpline, the charity will set up weekly phone calls between those in need and one of its trusted "Silver Line Friends".

The walls of Caroline's house serve as a reminder to the gaping hole in her life: dozens of pictures and posters of trains. Her husband, who died two years ago, was an avid railway enthusiast. Since he passed away, Caroline says that she has felt a searing loneliness. With her few family members all living in other parts of the country, she has come to rely on the weekly phone call with Wilma, which she has been doing for the past 12 months, for the human connection that it offers.

"I feel very lonely, I do," Caroline says with a heavy sigh. "I miss my husband dreadfully. But what can you do?"

This is Britain, the loneliness capital of Europe. And it really is. Last week, a survey by the Office for National Statistics voted us so, finding that we are less likely to have strong friendships or know our neighbours than inhabitants of any other country in the EU.

So we're not exactly best mates with next door; does it really matter? In a way, yes. Loneliness in Britain has never been more rife.

A survey conducted last year by The Silver Line discovered that 2.5 million older people in Britain described themselves as lonely. In a speech last October, Jeremy Hunt, the Health Secretary, called such statistics our "national shame".

And, as with other more obvious epidemics, it's affecting our health. Earlier this year, researchers at the University of Chicago aimed to quantify the effect that loneliness had on the elderly's wellbeing. Led by Professor John Cacioppo, their report, entitled Rewarding Social Connections Promote Successful Ageing, discovered that feeling lonely increased the risk of heart attacks, dementia, depression, and could disrupt sleep, raise blood pressure and lower the immune system. Those who felt isolated from others were 14 per cent more likely to have an early death. In short, loneliness is as bad for the health as that nasty 15-a-day Marlboro Light habit.

But with the percentage of households occupied by one person doubling between 1972 and 2008, it's no wonder we're in need of a bit of company. We might be living longer, but, it would seem, we are increasingly doing it alone. Pair that with the decline of community and an increased focus on work, and that makes for a lot of disconnected people.

Every week brings another heartbreaking story: men and women who are discovered in their homes years after their deaths, their disappearances unnoticed by anyone; the Irish pensioner, James Gray, who last year placed an advertisement in a newspaper for someone to spend Christmas with him because he couldn't bear to spend his 10th consecutive one alone. The news is full of Eleanor Rigbys.

But it is important to remember that it's not just the over-65s who are feeling cut off from the world. It's also, well, just about everyone else. The Lonely Society, a 2010 report commissioned by the Mental Health Foundation, revealed that 60 per cent of those aged 18 to 34 spoke of often feeling lonely. Emily White, the author of Lonely: Learning to Live with Solitude, was in her early-thirties when she began to experience feelings of chronic loneliness.

In quick succession, she started a new job in law, her father died, and everyone she knew was seemingly getting married and having babies. "I found myself on a variety of fronts – work, family, friendship – all starting to feel more isolated," she recalls. "I wound up in this loneliness spiral where things kept getting worse."

Despite finding herself going to the shops just so that she could exchange some words with the cashier, no one really spotted that she seemed to have developed a problem. "My material circumstances were very good," White says. "I was earning a lot of money and had a very impressive job and it didn't look like my life was empty. I think we have these categories of people who are allowed to be lonely and the elderly are one of them, recent immigrants another, and stay-at-home mums. If you don't fit into one of those categories, it becomes harder for people to make sense of what's going on with you because they're used to thinking about loneliness as an affliction of the elderly. And it's just not the case."

Married people, too, are not immune to the lull of isolation. A report last year published in JAMA Internal Medicine found that having a husband or wife to come home to didn't stop 62.5 per cent of married adults feeling lonely. It highlighted that the size of a family did not guarantee avoiding loneliness, reminding us just how tricky a state it is. Loneliness can slowly wrap itself around a marriage like a weed.

Similarly, the under-25s, young people who are constantly surrounded by others, whether in classrooms or nightclubs, are all too familiar with the ache of solitude. Most universities now run group counselling sessions specifically for loneliness.

Jessica Taplin, the chief executive of Get Connected, a charity providing support for young people, says that a quarter of those getting in touch have issues relating to emotional and mental distress, which can be linked back to loneliness.

"Young people at the moment face a relentlessly challenging environment, and, as a result, what we're seeing is that they're developing multiple deep-seated issues which just aren't being tackled, and these issues are making young people feel more lonely and more isolated, from both their peers and family," says Taplin. "Many young people we speak to admit they're too scared to share their feelings for risk of being judged."

Social media, that great connector, can exacerbate the problem among the young. Taplin admits that while the internet can be a wonderful thing for them, all too often people can feel surrounded by peers who appear to be out having a helluva time with their many mates. The result? A barrier towards genuine human interaction.

Jouelzy, a 28-year-old popular blogger specialising in lifestyle and beauty tips, recently wrote an article for xoJane.com about how, despite having a following of more than 100,000 viewers, she couldn't shake her loneliness.

"It's a paradigm that my generation of millennials are all dealing with as we exploit visibility for success, and are left feeling as though our real-life human connections rely a bit too much on seeing us on social media," she wrote. "When I turn on my camera to talk to an audience of 100,000, it boggles my mind that I still have an overwhelming sense of loneliness."

At the other end of the spectrum are those who are all too eager to advertise their feelings of isolation online. One of the most popular hashtags to use on Twitter and Instagram is simply #foreveralone, accompanied with a snap of anything from a ready meal for one to a sneaky forlorn selfie while a couple swaps saliva in the background. It's a joke, except it kind of isn't.

So how do we climb out of this well of loneliness? Jenny Edwards, chief executive of Mental Health Foundation, suggests that the responsibility doesn't rest with those suffering in isolation but rather that the onus should be on the whole of society. The Government is hardly blameless, either. "Spending time and recognising it's a good thing to spend time with other people is something that we as individuals all put too far down our list of priorities," says Edwards. "Loneliness has not been taken seriously by local government, and it is certainly not a priority because they feel there are more pressing things.

"But setting up local and neighbourhood social activities and schemes with small grants can really make a difference. Unfortunately, the effect of local funding cuts means that much has been lost. There are preventative public mental-health initiatives, but that's quite hard to evidence, isn't it?"

Research suggests that those experiencing loneliness are unlikely to tell others. So the best thing to do if you suspect that someone is lonely is to reach out to them – but, whatever you do, don't encourage them to "just get out there". It would seem that this is the most infuriating advice that can be offered.

"Loneliness is not always taken that seriously," says Jennifer Page, who wrote Freedom From Loneliness: 52 Ways To Stop Feeling Lonely. "I think it's probably the way depression was viewed about 50 years ago, and it has a stigma to it. People will say, 'Oh just pull yourself together and snap out of it.' But it's not that easy."

Emily White says that one tip she always gives is for the sufferer to learn what it is that they are experiencing. "I think loneliness is self-perpetuating and you've got to be able to spot what's happening to you. You've got to be able to understand what loneliness does to you psychologically and socially because it has a real effect. Read about it."

However, those approaching old age received some good news this week. Research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies shows that men's life expectancy should catch up with that of women, meaning fewer wives and girlfriends will be left behind. They predict that in 10 years, 38 per cent of people over 85 will be living with a partner compared with only 25 per cent today.

In the meantime, the thousands of organisations and charities across the country, from campus counselling services to The Silver Line, will strive to raise awareness of the problem and offer companionship and support to the lonely and broken-hearted.

"When I started at The Silver Line a year ago a lot of the people I called didn't do anything during the week or speak to anyone," says Wilma, the volunteer and Caroline's new friend. "Now they will try and leave the house to do something, just so when we speak next time they have something to tell me about. And that's good, isn't it?"

But it's down to all of us to be part of the solution. The more we talk about loneliness, the less of a stigma will be attached to it. Loneliness is here; it's not going anywhere. So say hello to the neighbour in the stairwell, call an elderly relative, have a proper conversation with your son. Communication – of any kind – is key.

The Silver Line helpline: 0800 470 80 90. If you'd like to be a Silver Line volunteer, visit thesilverline.org.uk

Jennifer Page's tips for dealing with loneliness

* Treat yourself with some kindness and compassion and find ways to nurture yourself. It might be a hot bath, a home-cooked meal or a long walk.

* Use the internet wisely. Sending a heart-felt email to a good friend sharing how you're feeling might make you feel better. Browsing on Facebook and seeing that other people's lives appear better than yours probably won't. Use the internet to find groups of people with interests similar to yours. Meetup.com is fantastic for that.

* Find activities that give you a sense of flow. For me, it's cooking and baking and then going for a run to work off the effects of the cooking and baking.

* Keep a journal. Buy a beautiful notebook and a pen you really like using.

* Explore your spiritual side. If church on Sunday mornings isn't for you, you could always try the Quakers or a spot of Buddhist meditation. Lots of places offer mindfulness courses too.

* Finally, remember that you're not the only one: most people feel lonely sometimes. Thinking that "it's just me! Everyone else is out there having a fantastic time!" just makes you feel worse.

Jennifer Page is the author of 'Freedom From Loneliness: 52 Ways To Stop Feeling Lonely'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments