Are smart drugs really that clever?

So-called 'smart drugs' have been seized upon by undergraduates as a means to stay alert and improve mental performance. But the long-term effects remain unknown. Rob Sharp investigates – and gets students' verdicts on the effects

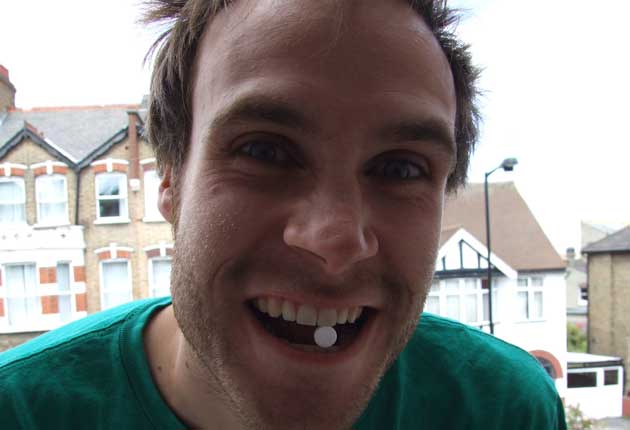

Two mates in their mid-to-late 20s are joking around. One of them pulls a silver blister pack from his pocket. It contains a rare drug, two pills of which he pops from the shiny wrapper that he holds in his hand. He gives one pill to his pal. They stand still for a moment, consider what they are about to do, before placing the capsules into their mouths and washing them down with a swig of water. They complete the move with a couple of mock-grimaces.

The drug in question is Modafinil, a form of prescription medication normally used to treat narcolepsy, but which is increasingly being abused by students across the US and UK for its stimulating properties: in small doses it can improve your memory, increase your focus and prevent you from falling asleep (proving especially handy in the run-up to exams). It is one of a group of cognitive enhancers or "smart pills" that also includes Ritalin and Adderall, both used to treat ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder), that have similar properties.

A study by Cincinnati Children's Hospital published in the British Medical Journal last month indicated that use of these latter two drugs in the US has increased by 75 per cent between 1998 and 2005. What's more, a 2005 survey of more than 10,000 US university students found that 4 to 7 per cent of them had tried ADHD drugs at least once to pull pre-exam all-nighters. At some institutions, more than one in four students said they'd sampled the pills. The subject is relatively unstudied in the UK but the trend is the subject of a forthcoming documentary, Wasted Britain, set to air on Current TV on 28 September.

"The problem is you don't know what you're getting," says Barbara Sahakian, professor of clinical neuropsychology at Cambridge University's psychiatry department. "We don't know about the effects of long-term use of drugs like Modafinil. We should wait for the studies to show the effect of it on healthy human beings. There are pressures on people but these quick fixes are not the way forward; education and exercise are both good ways of enhancing cognition, too."

Perhaps what is so worrying about the Current TV programme is the means by which its participants, Steve Middleditch and Christian Boyd, first got hold of Modafinil. "When the producers first told me to buy it I had never heard of it," says Middleditch. "So I began doing some research on the internet. I discovered that with a few clicks I could get hold of it by filling in a phoney prescription online. I said I had jet lag." A week later a pack of 30 pills arrived, postmarked Mumbai.

To conduct his experiment, Steve woke up one day at 3am to make himself fatigued, and took the pills at midday the following day. He describes the experience of taking the drug as odd, to say the least. "It's difficult to explain," he continues. "You get this massive buzz; it's a bit like drinking five cups of coffee in one go. You get a definite buzz off it. It affects areas of the brain rather than the heart. My hands were moving a bit. I definitely got the jitters. It's the sort of thing that not only keeps you awake, it keeps you blathering on. I certainly felt more focused. It was definitely stronger than I thought it would be."

The effects of the drug are well-proven. In 2003, Cambridge University researchers found a single dose helped male university students perform in mental planning tests, accurately complete puzzles and remember long chains of digits; it has also been tested by the US and British forces to allow soldiers to complete all-night operations. Scientists believe Modafinil can give its user 48 hours of continuous wakefulness (though there are some side effects: headaches are the most common, though there are plenty of others). The most remarkable thing, however, is that its users don't have to pay back sleep "debt" – a standard eight hours is enough to compensate for no sleep on the previous night: could this mean a future of 22-hour days? Our bosses may hope so.

"I would take Modafinil again because for me the problem is concentration and focus," says Boyd. "It allowed me to get down to what I wanted to do; I never felt like being distracted, so it was great." Philip Harvey, a professor at Emory University in Atlanta, says his work has been helped by Modafinil, which he takes to combat jet lag. Unlike in the UK, American doctors can prescribe the drug to night-shift workers as well as to narcoleptics. "I often fly to Europe to give talks," he says. "I used to travel the day before to give myself time to recover, but with Modafinil I can now give a talk the same day I arrive and feel like I've had a normal night's sleep."

Modafinil is not a golden drug, though. Its other side-effects may include insomnia, agitation, anxiety, agitation, and heart problems. And then there are the ethics of taking something that might give you an unfair advantage over your peers. "It's all in your personal preference," concludes Middleditch. "But I don't think it is a good thing. I can see why some people might take them. We've all had a deadline and been knackered and that pill will help you reach that deadline. In some scenarios where people need it I can also agree with it – some troops in combat might use it, or a paramedic might need it to stay focused. Perhaps there's some warrant in that. But personally it's not something I would take again, but that's just my feeling because it doesn't feel right. You become this person that you are kind of not. It's a strange feeling – the day after you still have this strange sensation in your head."

Ritalin and Adderall, which are defined by their active ingredients of mixed amphetamine salts and methylphenidate, as well as increasing concentration (in the right doses) can also be taken for the buzz they create. They are often used in combination with other drugs such as alcohol, or cocaine. Research conducted by Harry Sumnall, a psychopharmacologist at the Centre for Public Health at Liverpool's John Moores University, claims that research he has conducted in Merseyside shows that children with prescriptions for ADHD treatments were routinely selling their drugs; in some cases, so were their parents. "At least in the US they're looking out for the problem and routinely including Ritalin misuse in high school drugs surveys, for example," he says. "We might have to do the same here." These drugs are also less effective than Modafinil at enhancing performance.

"The biggest issue with these drugs, certainly with the likes of Adderall, is that it is very difficult to know how much to take; very quickly they can go from enhancing your performance to making you of no use whatsoever," says John Marsden, a reader in addiction psychology at the Institute of Psychiatry. "Though the principal issue is that if people were using these drugs it might set in train a process where people were using them more and more and become addicted to them."

'Wasted Britain' is aired on Current TV (Sky channel 183/Virgin channel 155) on Monday 28 September

Cognitive enhancers: Is it smart to take them?

Modafinil

Modafinil often comes in the form of the branded Provigil and is a memory-enhancing and mood-brightening stimulant, which enhances wakefulness. It stimulates activity within the brain and spinal cord (central nervous system). It is used to treat narcolepsy and sleep apnoea. It was rejected in 2006 by the Food and Drug Administration in America for prescribing to children with ADHD, but it is prescribed in the UK. Some of the side effects include unstable moods, blurred vision and difficulty sleeping. Ritalin – Tablets of Ritalin, one of the most widely known drug used to treat ADHD in children, contain the active ingredient methylphenidate hydrochloride. This is a stimulant and it is also possible to buy methylphenidate tablets on their own in an unbranded form. As well as calming hyperactive kids, it is used illegally by students to boost concentration and effectiveness at exams. The drug is still illegal without prescription in the UK, and is lawfully rated as class B in this instance.

Concerta

This is another branded version of methylphenidate hydrochloride, which has very similar effects as Ritalin. It is one of the newer brands on the market used to treat children with ADHD. The side effects seem less pronounced in children than Ritalin but there are still many, such as abdominal pain, nervousness and hostility. It is used less than Ritalin by students but for the same effects.

Adderall

Contains both amphetamines and dextro-amphetamines (amphetamine salts) and is widely prescribed as a drug to treat ADHD. It has four component salts which are claimed to metabolise at different rates. Manufacturers suggest that this makes the effects smoother. It is also used to treat narcolepsy and sometimes severe depression. The patient or drug user experiences more intense and sustained periods of concentration. It can cause psychotic episodes in those with a history of psychosis, though this is rare.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks