Abortion doctors: A matter of life and death

For abortion doctors going about their work in the US, the risks are constant. One, who paid the ultimate price, has inspired a new film

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On a warm spring Sunday, just after the morning service had begun at the Reformation Lutheran Church in Wichita, Dr George Tiller was handing out the church bulletin in the foyer when a stranger walked up, pointed a handgun at his head and pulled the trigger.

Three hundred miles away in Nebraska, his friend and colleague Dr Lee Carhart had just finished surgery and was preparing to meet him in Kansas for work, as he did every third Sunday, when his phone rang. As Dr Carhart held the receiver to his ear, all he could make out was crying. Through her tears, Dr Tiller's nurse, Cathy, finally managed the words: "He's been shot. The doctor's been shot dead in church."

Dr Carhart was devastated but, as events unfolded, not entirely shocked to hear that the police had taken Scott Roeder, an anti-choice extremist, into custody later that day for the murder of Dr Tiller, one of only five physicians in the United States who provided late- pregnancy terminations.

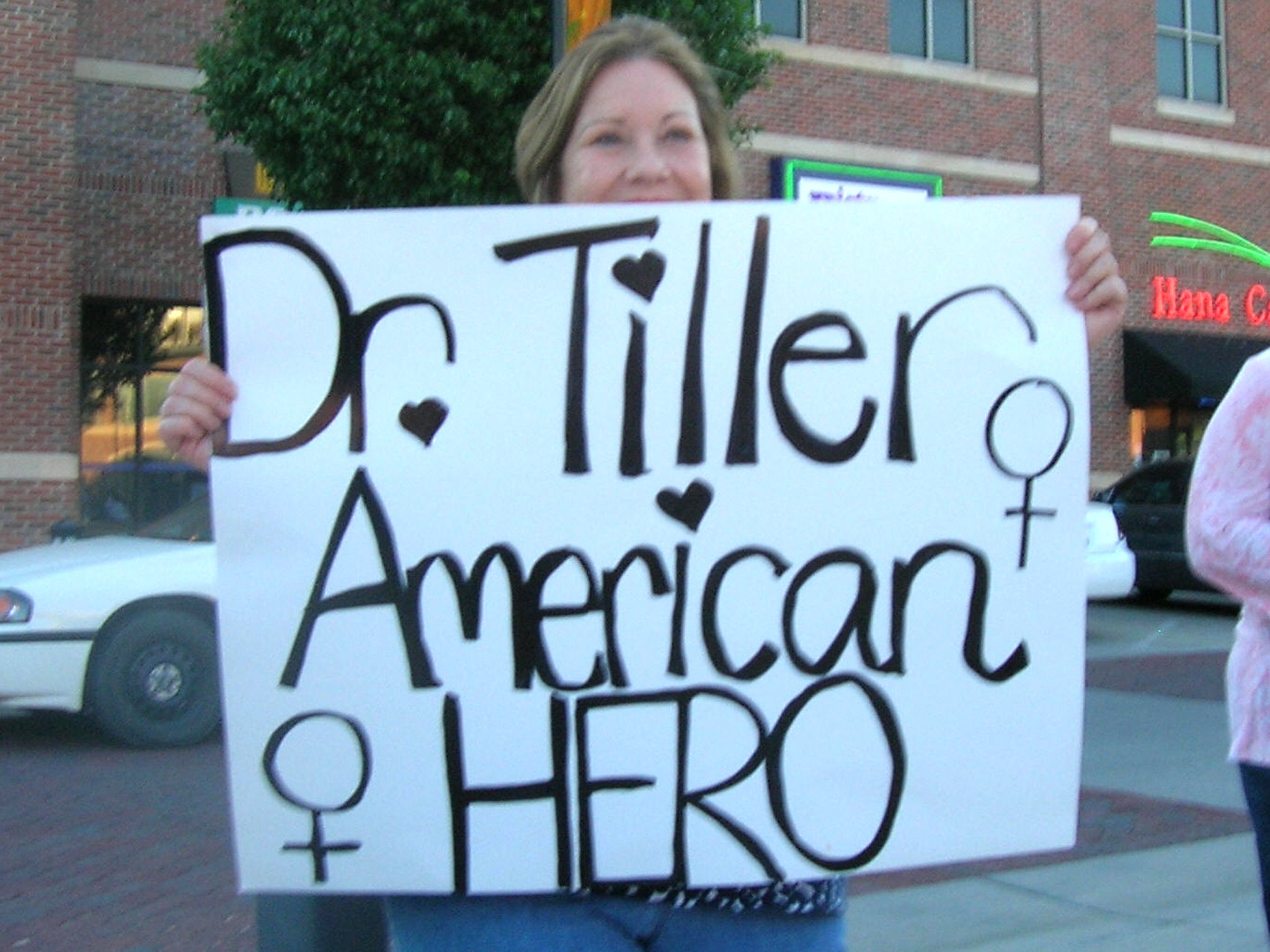

It was not the first time that Dr Tiller had been targeted. His abortion clinic was firebombed in 1986. In 1993, a pro-life activist shot him in both arms. Bloodied but unbowed, Dr Tiller, a former military medical officer, returned to work the next day and had an enormous sign erected outside his office which read: "WOMEN NEED ABORTIONS, AND I AM GOING DO THEM". But, with Roeder's successful attempt on his life on that Sunday in 2009, Dr Tiller became the eighth American abortion clinic worker to be assassinated.

During the five-hour journey along the interstate to Kansas, Dr Carhart and his wife, Mary, the administrator at his abortion clinic in Nebraska, spoke of their own future. "George and I had always known we were targets. The day he was murdered, there were no other thoughts in my mind but to carry on the mission," he tells me via Skype, his voice still defiant five years on.

The death of Dr Tiller inspired a new documentary that follows the story of his four colleagues – Dr Carhart, Dr Warren Hern, who operates a clinic in Boulder, Colorado, and Drs Sheila Robinson and Shelley Sella, who have a clinic in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

One of the film's directors, Lana Wilson, tells me how astonished she was by the nature of the murder. "It amazed me he was shot in the church where he and his family had been going to for over 20 years," she says, "and I just thought, 'Wow! I wouldn't expect the most targeted abortion provider in America to himself be a dedicated Christian'."

It was then that Wilson discovered that there were only four doctors left in the entire US who were performing second- and third-trimester abortions. "It seemed hard to believe that in a country of this size, so few physicians would be trained in doing late abortions, and so I became fascinated by what motivated these few," she says.

After Tiller, acclaimed for its humanist, non-political approach, made the official selection for Sundance Film Festival last year, where the premiere was guarded by armed security and the audience was required to pass through metal detectors because of the attendance of the four doctors who are the subject of the film. "It was really intense," Wilson recalls. "There were plain-clothes FBI officers and people planted in the audience who were trained in dealing with the mentally ill. When Martha [Shane, her co-director] and I walked to the podium, we were flanked by armed marshals to introduce the film. If anything, it made very tangible and present the real day-to-day threats that these doctors face."

In the film, Dr Carhart looks beleaguered as he talks about the daily harassment from anti-abortion organisations and individuals. The 72-year-old former US Air Force doctor has now become the No 1 hate figure for his opponents, who run petitions and websites calling on followers to "pray for" and "kick out" Carhart. Every day, before he leaves for work, he rolls a dice to decide which route he will take to his office, in an attempt to make himself a less predictable target.

As with Dr Tiller, he has been targeted by anti-abortion extremists for decades. His home and a 48-stall barn, along with two other buildings and vehicles, were set alight in a suspected arson attack in 1991, in which two family pets and 21 horses died. "The horses were just dead where they were in the stalls, just all on the ground and burnt," he says in the film. "Everything was gone. It was my daughter's 21st birthday and when we got the call, the police said, 'do you know where your daughter is?', and I said, 'I don't know, but I'll try to find her.' I finally got hold of her and she was safe." But as his wife adds tearfully, "that was the scary bit."

At the time of the attack, carrying out abortions formed only a small part of Dr Carhart's practice, but he acknowledges it as the point when he turned from provider to activist. "You know you don't give in to terrorists," he says. Undeterred, he began providing abortion full-time, saying that to do anything else "would have been the exact wrong precedent to set".

The fly-on-the-wall documentary captures what happens behind the closed doors at the clinics, many of the scenes involving patients who are seeking the most debated types of abortions in the US which account for under 1 per cent of the total performed each year. The definition of these abortions varies from state to state, but they take place in the second or third trimester of pregnancy, and are permitted only if it is believed that the foetus would not survive outside the womb, or that the mother's health is deemed to be at serious risk.

We meet one woman, "Monica", who is clutching a wet tissue. At 26 weeks into her planned pregnancy, she was told that her unborn son, Hudson, had a terminal condition. "There's no way to say when it could be fatal," she explains, weeping. "It could be in utero, he could be stillborn, he would have a very short-term life full of shunts, surgery and seizures before he would pass. All the doctors I talked to have said that the most loving thing I could do would be to let him go now."

Other cases of foetal anomalies, one of the most common reasons for women seeking these abortions, are discussed during the film, but there also cases involving the healthy foetuses of a very young woman who was raped, a single mother in poverty who had not been able to afford an abortion within the legal time limit, and others who are distressed, vulnerable and often suicidal. One woman does not meet the clinic's legal criteria and is turned away.

It was, says Wilson, hard to cover every scenario in the film. "It is all so complex, and that is what we wanted to get across," she says. "The more people you meet, the more you realise what lives of total chaos some of these people are coming out of."

The most recent poll, published in 2011 by Gallup, showed that only around 10 per cent of Americans supported the legality of these late-term procedures, meaning that many people who consider themselves pro-choice do not necessarily support such abortions. The lack of rational debate and the "rampant misconceptions" about these types of abortions formed part of Wilson and Shane's motivations for making the documentary.

Wilson says that, as with many people, she had known very little about the reasons why women opt for late terminations. "I was also surprised to discover that one of the major reasons why women seek these procedures is foetal anomalies, so in fact a large percentage of these cases are planned pregnancies," she says. "From experience, the first thing someone says when you mention [late abortions], is 'why would someone wait that long?', and the thing is that... no one is ever just waiting."

As Dr Carhart says, the reasons for women and couples visiting the abortion clinics are rarely simple. "If you're seeking an abortion after 24 weeks, it is usually because something has gone terribly wrong during that time. Either with that pregnancy, or that their lives just devastatingly changed or they didn't know they were pregnant, or they discover they have their own health problems," he says.

One of the biggest obstacles, Dr Carhart argues, is that abortions are so hard to obtain, and becoming more difficult because of the impact of anti-choice activists. "I had someone in my office today from Oklahoma who had been turned away from two other clinics first, and finally got to see us, but they lost four weeks in the process," he says.

The situation is now extremely pressing, thanks to a wave of legislation that began in 2010 with Nebraska's "Pain Capable Unborn Protection Act", which bans abortions after 20 weeks with only limited exceptions. This forced Dr Carhart to leave his home in Nebraska to set up a new clinic in Maryland during the filming of After Tiller.

A report published this month by the Guttmacher Institute also found that there have been more state abortion restrictions enacted in the past three years than in the entire previous decade. Dr Carhart reasons that this is because members of what he calls "the anti movement" have worked their way into positions of control within state and local government. "I think they're gaining strength," he says.

With increasing legal restrictions, the future of the practice is uncertain and may, according to the film's makers, "be on the verge of becoming illegal, inaccessible, or both". The doctors agree that the need for late abortions is not going to disappear soon and worry what measures women will take upon themselves. Dr Carhart has grave fears about how desperate some women might become. "When I was in medical school, it was during a time when abortion was still not illegal. There was this woman, I just looked at her cervix and knew something was wrong, and she just said, 'I tried using a chopstick,'" he says, a look of horror on his face.

Compounding the issue is the fact that all four doctors featured in After Tiller are approaching or already past retirement age: Drs Robinson and Sella are in their sixties; Dr Carhart is 72; and Dr Hern is 74. Dr Carhart hopes to bring a new doctor on board at his clinic, as do the two doctors in Albuquerque, who are also in the process of training another doctor. "If we could find people who were dedicated and would replace us, I think most of us would be sitting on a beach in retirement," Dr Carhart says, with a rare laugh.

Dr Tiller, too, had hoped to retire. As Dr Carhart recounts: "The Friday before he died, he called me and he said, 'I want you to come down Sunday because I am not going to be here. I plan on the three of you running the clinic because I want to spend time with my family.' He just really wanted to enjoy being a grandfather," he says. It was not to be. Days later, Dr Tiller lay dead in the vestibule of his church, his wife, a member of the choir, yards away inside the sanctuary.

Dr Carhart worries that, if anything, the threats have become worse since Dr Tiller's assassination, but says they had a mutual understanding of one another since the day they met. His face softens as he remembers that encounter, at a National Abortion Federation conference in Minneapolis in 1988, where they had both found it funny that they were the only people there who were wearing cowboy boots. "It led to a really great friendship. But George and I are both ex-military and the mission is first."

With that in mind, Dr Carhart continues to go to work each day in his abortion clinic in Maryland, where above his desk hangs a huge poster of the man that he and his colleagues will always remember as gentle, incredibly principled and brave. "George's life path affected all of us, you know. The only thing we have to do is to continue his work." µ

'After Tiller' is screening today and tomorrow at the Ritzy Picturehouse, London, and the Glasgow Film Theatre. For further sessions, visit: novemberfilms.co.uk/films/tiller/. It is available on iTunes and Curzon Home Cinema

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments