1 in 3 women will get bacterial vaginosis but are unlikely to know what it is

It may cause problems with pregnancy, and the infection has been found in some women who have had a miscarriage or a premature birth

One in three women will get bacterial vaginosis (BV), the most common cause of unusual vaginal discharge, at some time in their life. However, many women do not know what it is, and can confuse the symptoms for other conditions, such as thrush.

Although the causes of BV are not very well understood, it develops when the normal environment of the vagina changes, when there are less of the normal bacteria (lactobacilli), an overgrowth of other types of bacteria, and the vagina becomes more alkaline.

BV is not a sexually transmitted infection, but it can develop after sex, and any woman might get it including those in same sex relationships and those who have never had sex.

Activities that can put women at increased risk of BV include having sex with a new partner or multiple partners, using medicated or perfumed soaps, using strong detergents to wash your underwear, oral sex, douching (rinsing inside the vagina) or using vaginal deodorant or washes, and smoking.

Hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle, semen in the vagina after sex without a condom, an intrauterine contraceptive device and genetic factors may also play a part.

Around half of women with BV will not have any signs and symptoms at all, or may not be aware of them. Where there are symptoms, these can include an increase in the usual vaginal discharge, and for it to become thin and watery, change to a white/grey colour and develop a strong, unpleasant, fishy smell, especially after sexual intercourse. It is not usually associated with soreness, itching or irritation.

BV tests can be taken at a genitourinary medicine (GUM) or sexual health clinic, some general practices and some contraception clinics and young people’s services.

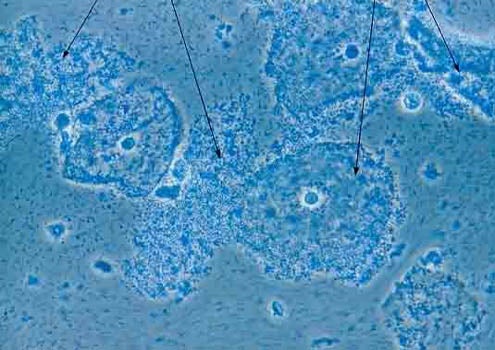

It is a quick and easy test and involves a doctor or nurse using a swab or small plastic loop to collect a sample of cells from the walls of the vagina. It only takes a few seconds and is not usually painful.

The pH (alkaline/acid balance) of the vagina may also be measured by wiping a sample of vaginal discharge over a piece of specially treated paper. In some services, the result is available immediately, while in others a sample is sent to a laboratory, and the result is usually available within a week.

Treatment is simple and involves taking antibiotic tablets, either as a single dose or for up to a week, or a cream or gel for use in the vagina for around one week. These treatments are very effective though it is quite common for BV to return, and some women get repeated episodes.

In these cases, women may be given a course of antibiotic gel to use over a number of months and others may be given antibiotic tablets to use at the start and end of their period. Some women may also find it helpful to use a lactic acid gel, which can help to restore the pH balance in the vagina.

Although women sometimes worry that BV can affect their chances of getting pregnant, there is no evidence this is true. However, it may cause problems with an existing pregnancy and the infection has been found in some women who have had a miscarriage, a premature birth or a low birth weight baby.

BV can safely be treated during pregnancy and when breastfeeding, so it’s important to let doctors and nurses know about the pregnancy so the best type of treatment can be prescribed.

For information on how to find a service to test for BV or any sexually transmitted infections, visit FPA’s How to get help with your sexual health page

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks