Drug related deaths are at their highest level in 25 years – here’s why

Synthetic opiates are a growing problem

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last year saw the highest number of drug-related deaths since records began in 1993, according to data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). More than half of these deaths involved an opiate, such as heroin. Those aged 40 to 49 years old made up the largest group dying as a result of drug poisoning. Compared with the general population, this group are dying decades before they should.

For the population as a whole, life expectancy has stalled since 2010. This is not inevitable as the UK is not yet achieving the average life expectancy of countries such as Japan and Sweden. In a recent blog, Sir Michael Marmot said there was an urgent need to determine if austerity had contributed to the shortening of lives.

This makes politicians uncomfortable, as can be seen from this Twitter exchange between Marmot and the Health Secretary, Jeremy Hunt, who tries to cast doubt on the data:

Fentanyl

Synthetic opiates, such as the fentanyls, have contributed to the rise in opiate-related deaths in the US. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, which is responsible for monitoring drugs, identified 18 new fentanyls through its early warning system, and recently issued a risk assessment on a new drug of concern, furanylfentanyl. In England and Wales, deaths due to fentanyl have increased from 34 in 2015 to 58 in 2016, and it is suspected that this is an underestimate because toxicologists don’t routinely test for it.

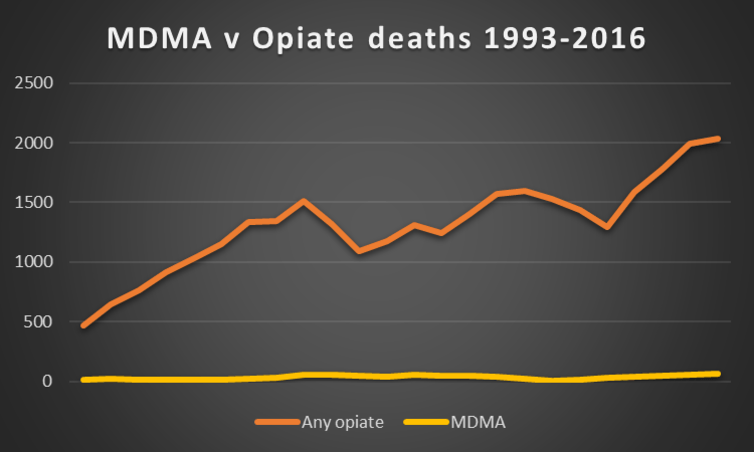

Historically, there has been disproportionate attention paid to deaths attributed to MDMA (usually sold as ecstasy). MDMA deaths in the UK have increased from 57 to 63 a year, the highest ever number, but these deaths are newsworthy because they are still rare, considering how many people take ecstasy each year.

However, while ecstasy deaths are atypical in relation to the overall burden of drug-related deaths, one analysis of Scottish newspaper reports in the 1990s showed that while all ecstasy deaths made the headlines, only one in nine opiate deaths – and one in 130,000 tobacco deaths – were reported.

This discrepancy is probably still evident and is important because reports of deaths are often used as a platform to advocate for change in policy and practice. While there was a welcome media focus over the summer on harm reduction strategies, such as drug checking at clubs and festivals, there has been a lack of equivalent focus on opiate deaths, perhaps because of who typically uses opiates compared with who uses ecstasy: younger people, with good social support networks, tend to die as a result of ecstasy, whereas heroin users are often older and lack positive relationships with family and friends.

Why are people dying?

It is difficult to know what impact austerity has had in shortening the lives of people who use drugs. But is it a coincidence that since the change in policy in 2010, which saw a move from trying to reduce the harm that drugs cause to one which promoted abstinence, more people have lost their lives?

It is unlikely that a single factor explains this rise in deaths. Rather a constellation of elements. We have an ageing cohort of opiate users who are developing physical problems. Variability in the purity of heroin will also be a contributing factor. Being in treatment reduces the risk of overdose and death but there are variations in treatment. Ensuring patients receive the right dose of an opiate substitute for long enough is one area we could improve as that has been shown to reduce mortality.

It is encouraging that the Government has made commitments to support high quality, methadone-based drug treatment, and the wider use of naloxone, a drug used to reverse the effects of an opiate overdose. Some 90 per cent of local authorities report that they have made take-home naloxone kits available to drug users, with the remaining reporting that local drug deaths were too low to warrant introduction.

However, in a 2016 report to government, the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs made a number of additional recommendations to reduce opiate deaths, including the introduction of medically supervised drug consumption facilities. The recent European Union action plan on drugs has also encouraged member states to adopt this approach.

Unfortunately, the Government has replied that it has no plans to act on this particular advice. While it has stated that it is up to local areas to determine how to respond to drug users’ needs, the reality is that without central Government support and funding, local authorities are unlikely to introduce these potentially life saving measures on their own.

Ian Hamilton is a lecturer in mental health at the University of York; Harry Sumnall is a professor at Liverpool John Moores University. This article was originally published on The Conversation (www.theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments