How a little girl's rashes turned out to be a rare immune deficiency disorder

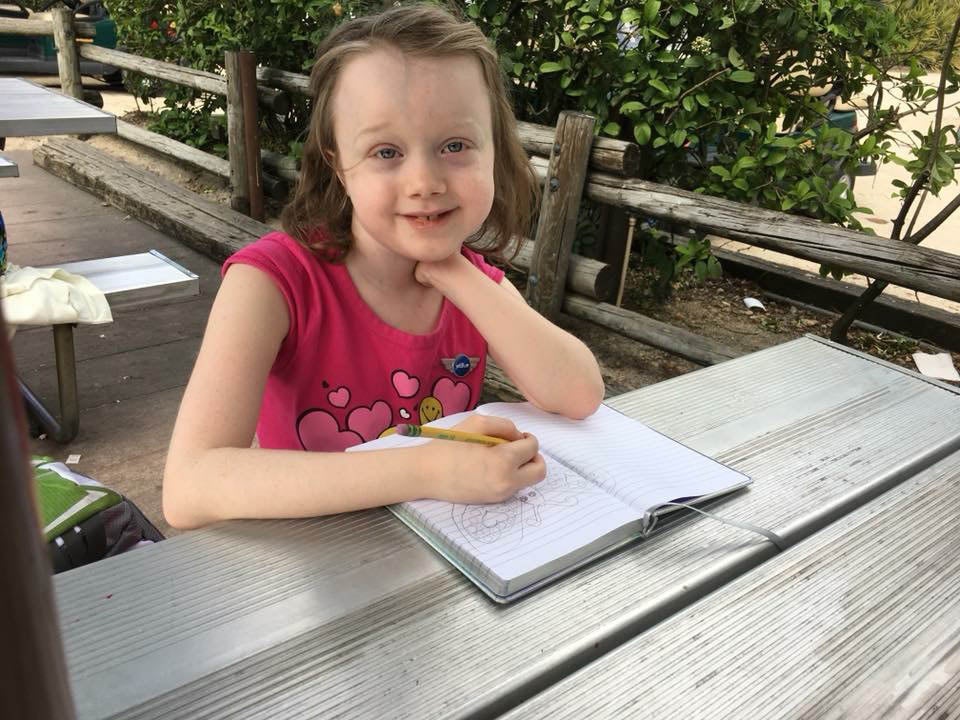

Lucy Wiese's parents weren't too worried about her persistent skin rashes and infections – but then she was diagnosed with a condition that affects one in a million

The paediatrician was blunt but not unkind. Even so, her unequivocal message made Jan Wiese bristle.

“You know, this is really not normal,” the doctor told Wiese after seeing two year old Lucy Wiese for the first time. Struck by the little girl’s medical history, especially her repeated skin infections, the suburban Washington doctor recommended Lucy see a paediatric immunologist in Baltimore.

“I was kind of offended,” Ms Wiese recalls of the encounter. It had not occurred to her or her physician husband that their daughter’s infections might signal something more serious than a toddler’s normal – if acute – susceptibility to unfamiliar germs.

Years later, Ms Wiese ruefully recalls how indignant she felt. “Of course she was right,” she concedes.

In the months following that routine 2010 appointment, it would become clear just how extraordinary Lucy’s medical situation was. Timing and luck proved crucial: a serendipitous encounter with a specialist expedited a diagnosis that can take decades. And proximity eased Lucy’s access to one of the world’s pre-eminent treatment centres.

Over the past eight years, Lucy’s odyssey has consumed her family, who have marvelled at the youngster’s ability to survive repeated setbacks and endure some of medicine’s most arduous treatments. Her precarious health, which had been spiralling downward, appears to have rebounded in recent months.

“She’s just a really spunky kid,” her mother says. “It’s really a miracle that she’s here.”

Lucy’s birth, in June 2008 at a hospital in Richmond, Virginia, followed an uneventful pregnancy. Doctors noted what they characterised as a benign newborn rash that blanketed her body. To Ms Wiese, the rash resembled little freckles, which scabbed over and fell off. Lucy also had a mild case of jaundice – common in newborns – which required a week of light-exposure therapy at home.

At nine months she developed an infection near her toenail. The area grew swollen and pus filled, but wasn’t painful. A paediatrician drained it and the toe healed.

Three months later, something similar happened to two of Lucy’s fingers, which she habitually sucked.

“It really looks like she’s been burnt,” one doctor told Ms Wiese, who assured him that was not the case.

“Luckily, they believed me,” Ms Wiese says. Lucy was given antibiotics, and the doctor advised she be prevented from sucking her fingers – easier said than done, her mother says.

Lucy had also developed periodic patchy outbreaks on her face and torso, that resembled a heat rash and puzzled her doctors.

Ms Wiese and her husband Scott, then a fourth year medical student, thought Lucy might simply be vulnerable to the germs he was bringing home from the hospital.

Around the time of her first birthday Lucy’s family moved to Charlottesville, Virginia, where a new paediatrician noted the large size and unusual shape of her head, which was long and narrow.

“We have kind of big heads in our family,” Wiese told the new paediatrician. After a CT scan revealed sagittal craniosynostosis, a birth defect that causes premature closure of the bones in a baby’s head, Lucy was referred to a paediatric neurosurgeon at the University of Virginia. He deemed her case mild and recommended against surgery, which can be risky.

Five months later, Lucy developed an abscess behind her left ear. More serious than the previous infections, it needed to be surgically drained and required she be hospitalised for intravenous antibiotics. This infection, unlike the previous ones, healed more slowly and required a round of oral antibiotics as well as corticosteroids.

Around the time of Lucy’s second birthday the family moved again, temporarily settling in the Washington suburb of Reston, Virginia. A few months later, Lucy saw the paediatrician who recommended the immunology visit to Baltimore.

Lucy’s parents agreed, and she was placed on a waiting list at Johns Hopkins hospital. But weeks before her third birthday the little girl developed a severe case of oral thrush, a fungal infection that causes white patches inside the mouth and oesophagus.

“It was so painful she couldn’t swallow her own saliva,” says her mum. Lucy was admitted to MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, where her father was an anaesthesiology resident.

An infectious disease specialist noted that thrush, one of the opportunistic infections that can affect patients with HIV, was extremely unusual in a patient of Lucy’s age, and strongly suggested she might have a malfunctioning immune system.

Less than a month later Lucy was back at Georgetown with a second, severe case of thrush. This time she saw Charlotte Barbey-Morel, then the hospital’s chief of paediatric infectious diseases – Barbey-Morel has since retired and moved back to her native Switzerland.

Ms Wiese recalls the specialist told her she was fairly confident she knew what was wrong. One of Barbey-Morel’s colleagues, who split her time between Georgetown and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), had treated patients with a rare diagnosis whose symptoms sounded a lot like Lucy’s.

“Charlotte called me and said, ‘You’re not going to believe it, but I think I have a patient with that disease’,” says Barbey-Morel’s colleague Alexandra Freeman, now director of the primary immune deficiency clinic at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “I would talk about these kids all the time. There was a lot of serendipity that Lucy happened to go there and that I had been working there. But it was really Charlotte who figured this out.”

Lucy’s symptoms were consistent with a rare disorder called Job’s syndrome, also known as Hyper IgE syndrome. The immunodeficiency, which is estimated to affect roughly one person in a million, is caused by a mutation in the STAT 3 gene.

The defect over and understimulates the immune system, causing severe bacterial and fungal skin infections that result in lesions and boils – hence the biblical moniker. Other features include lung infections, fractures, skeletal problems – including a curved spine, or craniosynostosis – hyperflexible joints and dental problems.

Some cases of Job’s are inherited – a parent with the disorder has a 50 per cent chance of having a child with it – while others occur as a result of a spontaneous mutation.

There is no cure Antibiotics and antifungal drugs are commonly prescribed to prevent and treat related infections and a definitive diagnosis requires sophisticated genetic testing. The best place to get that, Barbey-Morel told Ms Wiese, was NIH, home to one of the world’s largest Job’s treatment programmes. In 2007, two teams of scientists – one of them from NIH – identified the gene responsible for a disorder first reported in 1966.

In early 2012, testing revealed Lucy had the mutation and because her parents and younger brother do not, Lucy’s case is not considered hereditary.

For her mum, Lucy’s diagnosis was difficult but not unexpected. “I was starting to get a little bit desperate,” she says. “I think we were just feeling like, finally, we can get some answers.” She enrolled her daughter in a long term study of the disorder Freeman is conducting.

The doctor, who has seen about 130 Job’s patients, said that unlike patients many in her study, Lucy was diagnosed at a young age. Some of the others, who include multiple generations from the same family, were not diagnosed until they were in their 40s, although they had been ill virtually their entire lives.

“This disease is especially tricky because it’s multisystem [condition],” Freeman says.

When she was four, Lucy landed in Georgetown’s paediatric intensive care unit with a lung infection that nearly killed her, and led to a cascade of recurrent severe infections.

Three years later, in the spring of 2015, Freeman proposed an experimental treatment: a bone marrow transplant. While unlikely to provide a cure, a transplant might reduce the severity and frequency of Lucy’s lung disease, which posed a continuing threat to her life, Freeman said.

The Wieses, who had moved back to Richmond, agreed a transplant was worth a try, and Lucy became the first of three Job’s patients at NIH to undergo the gruelling procedure. “Her parents are amazing,” Freeman says. “They’re so upbeat.”

“I knew it wasn’t a cure, but it was an experimental procedure that could help her,” said Jan Wiese.

Lucy and her mother spent months in the Washington suburb of Bethesda, shuttling between NIH’s clinical centre and the Children’s Inn, a free residence for severely ill children undergoing treatment at the research hospital.

In March 2016, about three months after the transplant, Lucy suffered a serious setback when her right lung collapsed as a result of pneumonia, and underwent surgery at the Children’s National Medical Centre.

“I remember bursting into tears when [the surgeon] came out and told us she had done so well,” Ms Wiese says.

In the past year Lucy’s health has improved significantly.

“She’s doing much, much better,” says Freeman, who saw Lucy in June, adding: “Her lungs are looking really good,” and the patient has had no skin infections since the transplant.

“We’re hopeful that the transplant and lung surgery helped her turn the corner,” her mother says before adding that although Lucy is being homeschooled for health reasons, “she’s got friends”, and in many ways her life is no different to that of other 10 year olds.

“We do anticipate her going to college one day,” her mum says. “I do think and hope she’ll live a normal life.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks