Stop calling teen boys toxic – the problem might be us

We call them ‘bros’ and criticise them for their sexist attitudes and aggressive behaviour, but, could there be something deeper going on? Steve Biddulph, considered the world’s leading expert on raising boys, thinks so and tells Lorraine Candy that we need to look at our own behaviour before criticising theirs

My son has just turned 18. Next year, he will leave home for university, following in the footsteps of his two sisters, aged 20 and 22. His younger sister, aged 13, will be left behind with us. We’ve been through the wringer parenting three amazing teenage girls, for sure. But at no point have I been as scared for them as I am for my teenage son. Raising a boy has felt much more challenging, confusing, and risky in this social climate.

In no particular order of importance, I worry about the following: will my son be stabbed in our nearby London park or violently robbed walking home from school? (The latter has already happened to at least two of his friends.)

Could their quiet way of hiding depression make my son vulnerable to the terrifying reality that boys are three times more likely to die by suicide than girls? Is he gaming excessively? How much misogynistic porn is he secretly watching? Will my vocal feminism turn him into a woman-hating incel? Is his self-esteem – fragile yet crucial during adolescence – robust enough to survive the adult world?

I catastrophised about my daughters too, of course. The difference is, I felt in control when guiding them. I understood their feelings, knew about their bodies, and saw how today’s warped version of masculinity could put them at risk as they matured.

After all, I am, as Gregg Wallace would say, a “middle-class woman of a certain age” (56). I am well aware of the unhealthy “manosphere” that supports the Gregg Wallaces of this world, and I developed ways to help my teen daughters cope, avoid, or fight against it. I knew what to do. With my son, I am not so sure.

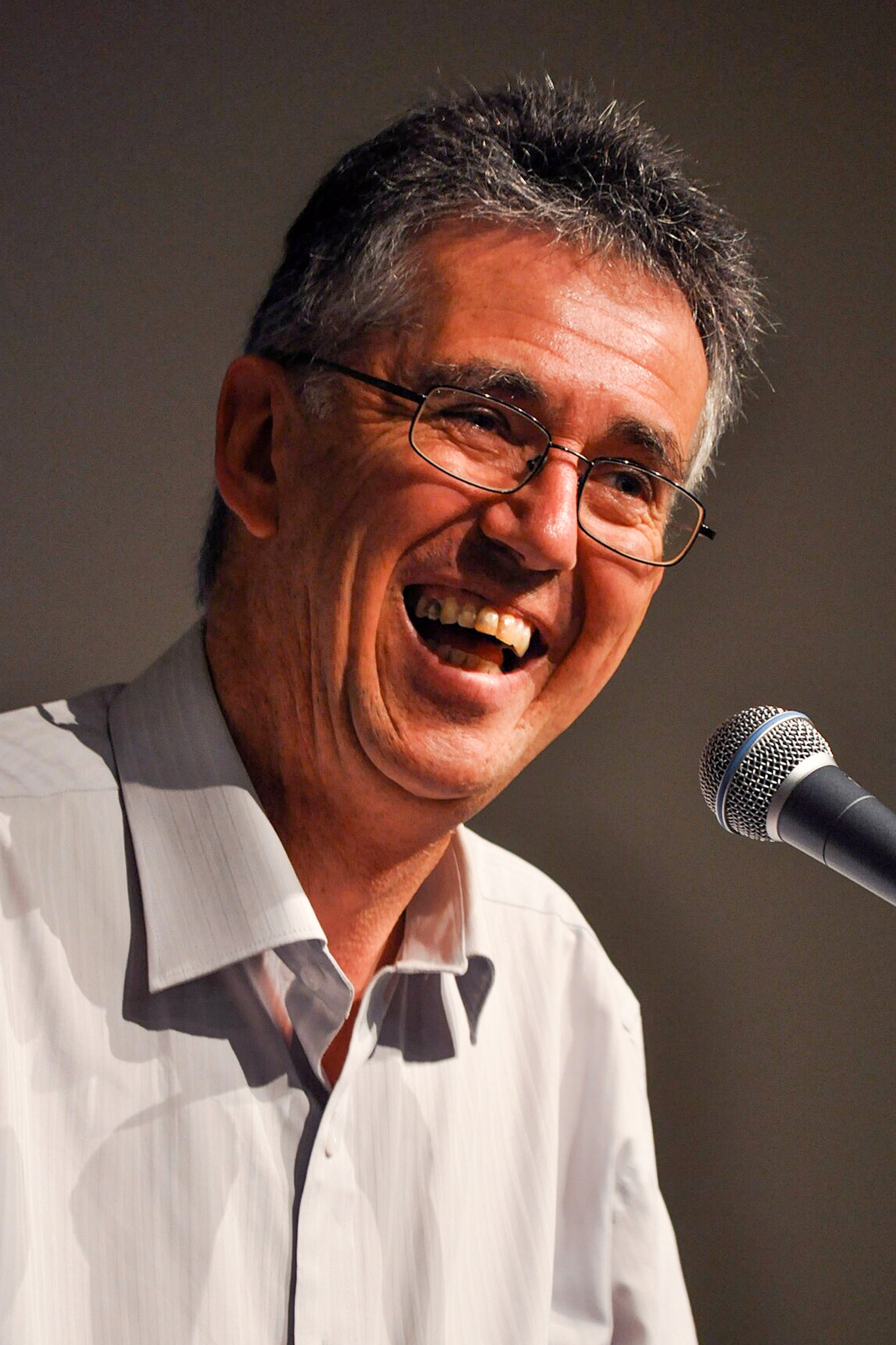

In 2017, I interviewed psychologist Steve Biddulph, the award-winning author of the 1997 book Raising Boys, which sold almost five million copies. I recall a somewhat confrontational conversation about how it was not the internet or mobile phones causing problems but rather today’s affluent, time-poor parents, who were responsible for the teen mental health crisis. This was pre-pandemic, which studies show adversely affected boys’ mental health more than any other demographic.

On the eve of my son’s 18th birthday last month, I spoke to Biddulph again. Now 71, he has written a new book, Wild Creature Mind: The Neuroscience Breakthrough That Helps You Transform Anxiety and Live a Fiercely Loving Life. It felt like a good opportunity to revisit our earlier conversation and hear from him why I’m finding parenting my teenage son harder.

Biddulph, now considered the world’s leading expert on raising boys, explains that boys today feel trapped in a world where the concept of the “manly man” – at all costs – is undergoing a rebirth. The alpha male is back, underpinned by a sense that many boys have lost sight of what being male and a man can mean.

“Messed-up masculinity, from the streets to boardrooms to dictators’ palaces, is destroying our world,” he says. “It’s the common link dominating our news feeds, and, in a sense, I have been campaigning my entire life to prevent it from ending up like this.”

Teenage boys today have witnessed the #MeToo movement rightly calling out misogynistic men, but perhaps they haven’t fully grasped the nuanced arguments about masculinity’s place in the movement. These boys are growing up in an environment where consent is discussed as if they are already guilty – or potentially guilty – of heinous behaviour towards women. The tone feels personal and, at times, accusatory, as if they alone are the problem rather than society’s entrenched patriarchal views of ownership over women.

I think this has left many younger Gen Z boys confused, provoking a sense of powerlessness in the face of vocal feminism. I am not blaming feminism per se – women have needed it more than ever to express what they face in society – as patriarchal structures need to be continually challenged.

But I also see my son emotionally step back when my daughters relay stories of being sexually harassed on public transport or in the pubs where they work. I fear he is thinking, “What do you want me to do?” Perhaps it weighs heavily on him at a time when, neurologically, he is just beginning to make sense of his emotions – though expressing them as a boy is still considered unusual or out of the norm.

Girls are socialised to show their feelings from a young age, but even in our so-called progressive times, we still don’t do well with boys. Teen boys often don’t know which male “tribe” they belong to, at a time when the need to belong is a neurological imperative.

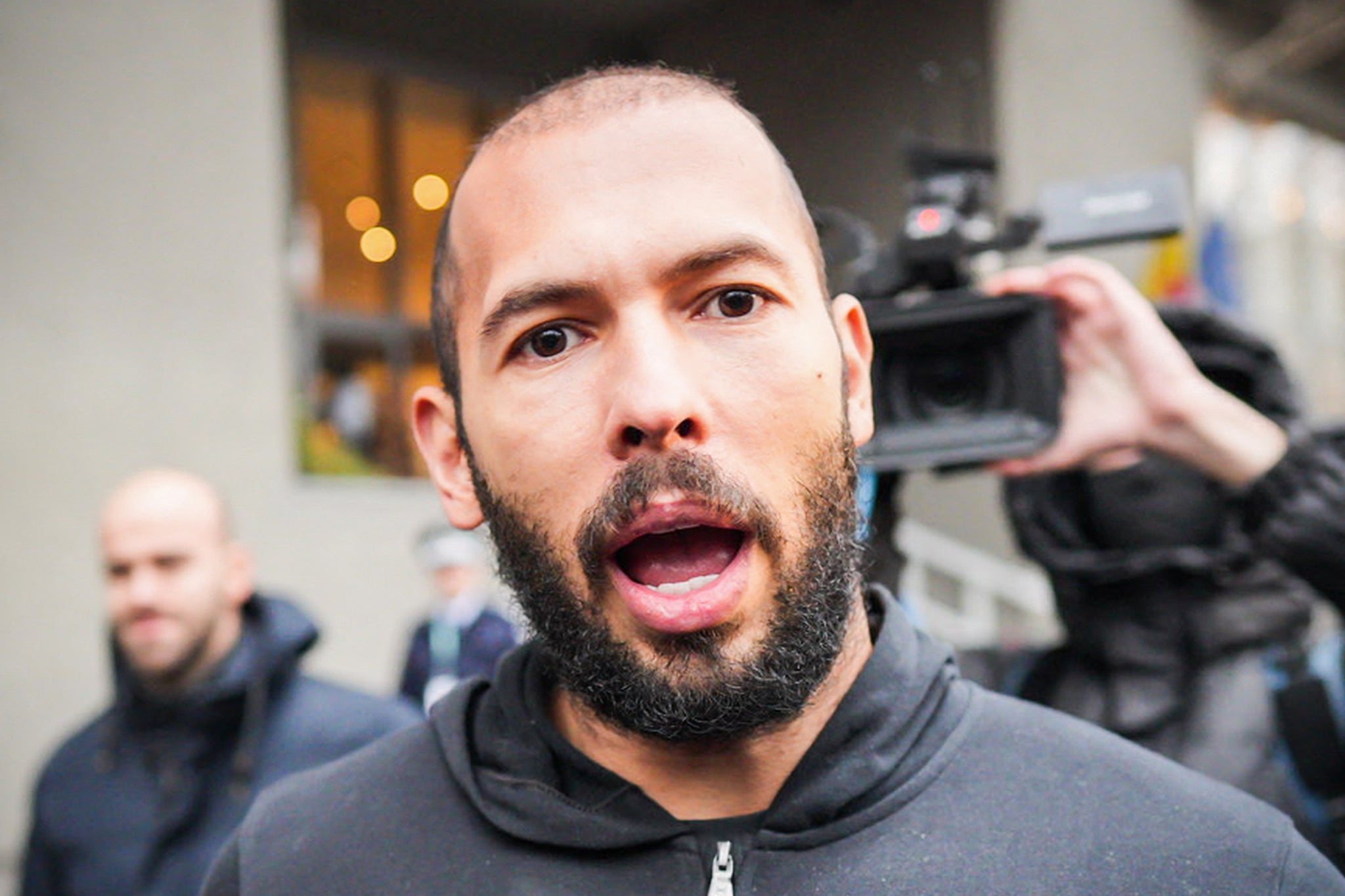

Family therapists recount how boys feel lost and alienated in adolescence, particularly around the crucial developmental stage at 14 years of age. It’s no surprise, then, that the stronger and louder voices of the messed-up “manosphere” – figures like Joe Rogan and Andrew Tate – may appeal to tribeless teen boys who feel powerless and, yes, scared to show their true selves or any vulnerability because society doesn’t “allow” it.

Biddulph notes that while there has been much talk of men opening up about their feelings, this has only “caught the low-hanging fruit”.

“Over several decades, the buzz around raising boys better has made sense,” Biddulph explains. “My book encouraged dads to play with their children, be engaged, and stand alongside their spouses. Parenting became a team effort – a significant social revolution, the linchpin of making boyhood work and feminism work too.

“But you can’t, in one generation, change the damage that maleness had carried from the blight of the industrial revolution, the wars and trauma that shut down a generation of men: the alcoholism and violence of life back then, and the bizarre distance and posturing of affluent and privileged upper-class men.”

Masculinity is modelled across generations, making it a tough pattern to break. Not enough Gen X men stepped away from their fathers’ and grandfathers’ ingrained behaviours to allow their Gen Z sons to accept equality and embrace a healthier vision of manhood.

“We have a significant cohort of boys and young men raised by inadequate fathers,” he says. “Misogyny acts as a shield for their deep insecurity around women and girls, giving them the illusion of self-worth through a myth of superiority.”

Some of us have shown our sons one version of equality and “good” masculinity at home, but taking that out into the world remains a daunting task for a teen boy, as societal attitudes shift more slowly.

Many boys today feel unseen and unheard. Think about how the “bro” vote helped win the US election: 56 per cent of 18- to 29-year-old men voted for Donald Trump. They felt that Trump spoke directly to them, meeting them where they were, on podcasts and platforms they engage with. Ignoring this is perilous because there’s one thing all teens hate more than anything: when their elders don’t listen to them.

The worlds and spaces deemed for them – gaming and porn – are dripping with misogyny. The bullies with the loudest voices are seen as strong leaders advocating for them. The fact that these “strong” men have discovered their voices as a response to a sad and weak, probably conflicted, interior life is hidden from view. It’s not okay to talk about feelings, and many dads still hand over the emotional support of teen boys to the nearest female.

“We are at a tipping point for boys in history,” Chloe Combi, a podcaster, author, and researcher who is an expert on Gen Z, tells me. “We need to take this more seriously. The gender divide is the problem. Girls have been fed this idea that all boys are potential rapists; boys, in turn, were told feminism is dangerous, and girls are humourless.

Messed-up masculinity, from the streets to boardrooms to dictators’ palaces, is destroying our world

“Out of that, these ‘fake’ men emerged – pretenders to masculinity like Andrew Tate. They became the counterculture for young boys. Rebelling is how boys show individuality, and perhaps some are trapped into shocking their parents by following awful role models.”

This fake alpha male attitude is often reinforced online via social media, particularly in the hyper-masculine sporting world. On some subjects, platforms like X (Twitter) can be cesspools of uncensored, vile anti-women trolling that is then served up to football-loving boys like my son.

Lest we forget, we’ve also seen a man who sexually harassed women and made misogynistic comments on the world stage become a president. Men known as sexists, and even predators, are celebrated as national TV treasures, even when their behaviour is widely known.

Some young men living in this world are exhausted by, what they feel, is being blamed for all bad male behaviour. At some schools they are told they are “privileged”, even when they are often just unsure, spotty youths grappling with brains undergoing a seismic rebuild and often surrounded by seemingly fearless teen girls.

Boys may hide their vulnerability, but science shows that they are physiologically and emotionally weaker than girls from the womb onward.

In Ruth Whippman’s book BoyMum, she cites studies showing that boy babies are more fragile. They are more likely to be born premature, and full-term male babies are more likely to die of almost every illness. Virtually all neurological and learning disabilities are more common in males. Male babies also cry more than female babies and are shown to be more vulnerable to environmental stress. The ability to self-regulate and cope with anxiety is much harder for boys of all ages.

Freddie Flintoff’s extraordinary Field of Dreams documentary on the BBC, where the ex-sportsman strives to create a new cricket team of teenage boys, is a striking example of how hard that demographic, with all their big-hearted energy, find it to fit in with what society demands and expects of them. Boys mature physically later than girls and, emotionally, seem much younger than their female peers. Many can’t show their true selves to each other – or even themselves – so how on earth are they meant to show up for the rest of us?

While girls worry about their mental health, boys worry they will fail in life. Chloe Combi spends her time travelling to schools all over the UK to talk to adolescents – more than 20,000 to date – as part of her Respect Project, which encourages older girls to mentor younger boys rather than see them as the enemy.

“We have lost the idea of a grey area up for discussion in the middle,” says Combi. “Most boys don’t hold extreme opinions, but there is no safe space for them to vocalise that anymore.”

So, if many of our boys are feeling shut down in every way, what do we do? How can we help the majority of boys, like my son, who may be stuck in that grey area? It’s no easy task, says Biddulph, but it starts young, and six is the crucial age to proactively focus on raising a happier, stress-free boy.

Boys need an engaged, safe, and reasonably happy dad and male role models around them. There are three types of defective fathers, he explains: critical (the way Trump was raised, Biddulph adds); distant, meaning home but preoccupied; and “the inadequate man”, a friendly but ineffectual parent.

“A son also needs a broad-based masculinity that is unique and his own, especially from the mid-teens onward, so that he steps beyond the family and into the world,” Biddulph says.

Biddulph is keen to stress that single mums can raise great sons but adds that a young person also needs to “mesh” with others they see as “like them” outside of the family. Men like Marcus Rashford, Stormzy, and Flintoff, even Jamie Oliver, can all play into a new sense of masculinity for our boys.

Combi says that by far the happiest boys she has met are those with interests outside the home and beyond gaming and the internet. “Those in teams where winning is not the goal, and those with hobbies,” she says, adding, “This is true across all socio-economic groups.”

To stop young boys and men from carrying a sense of shame, we need to rethink our use of terms like “toxic masculinity” in a throwaway manner. It lands on them heavily. We also might need to celebrate that crazy, physical energy I witness when I see a group of teen boys tumbling out of the school gates, jostling each other and standing close together. From nursery onwards, many spaces frown upon robust and noisy physical play, celebrating the easier-to-manage, quiet and contained instead.

The exuberance of a teenage boy is very different from that of a teen girl, in my experience, but we don’t always see it as joyous. We need to love them as boys, keep the lines of communication open, tackle difficult subjects, and show them it is okay to talk – talk, and talk some more about everything (do this side-by-side; no teen likes a face-to-face chat!).

In trying to meet my son where he is, I have had to step into his mind with empathy, not sympathy. I don’t feel sorry for him; I try to see opportunities for him and cherish his maleness in a world that can sometimes demonise it.

But, more than anything, it seems that boys need their dads and male caregivers to lean into their limelight with kindness and care, giving them the confidence to reveal who they really are. It can’t be a coincidence that some of the most problematic characters around – from Trump to Elon Musk and Russell Brand – all had fractured and painful relationships with their fathers.

Combi says, “Boys and girls need to be reminded of each other’s humanity.” And Biddulph adds, “To be a good man, you have to see a good man.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments