Healing with paint: How the pioneer of art therapy helped millions of mental health patients

Edward Adamson was the first artist to be employed in a UK hospital. Kashmira Gander explores how his studio was an oasis of calm in a harsh twentieth century mental hospital, and how his legacy lives on.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is the late 1990s and once again Gary Molloy’s severe bipolar disorder has hospitalised him. Unbeknown to Molloy, though, this stint will be the one to transform his life. “I saw these wonderful paintings on the ward. They were quite abstract. I was mystified and inspired, ” recalls Molloy, now 47, of his stay in a hospital in east London where he was born and raised.

Gripped, he needed to find out more, and discovered the works were created at Core Arts, a nearby centre for people with mental health illnesses. This is how Molloy, who was deterred from creativity by his teachers because of his gift for maths, says he discovered art.

“I found something magical in painting, writing and poetry. It eased the symptoms,” says the civil servant turned artist who is now a trustee and volunteer at the centre. “Ever since, I’ve been managing my condition by being creative, and building my self-esteem. It was a catalyst.” The impact on Molloy is undeniable: he hasn’t been hospitalised for 17 years.

Art as therapy was first used in the early and mid-20th century. Patients were often forced to deal with archaic and brutal practices, but they were also first to experience pioneering treatments. This duality, as well as how mental health has been approached over the centuries, and what the future might hold, is being explored at the Wellcome Collection’s latest exhibition: Bedlam: the asylum and beyond.

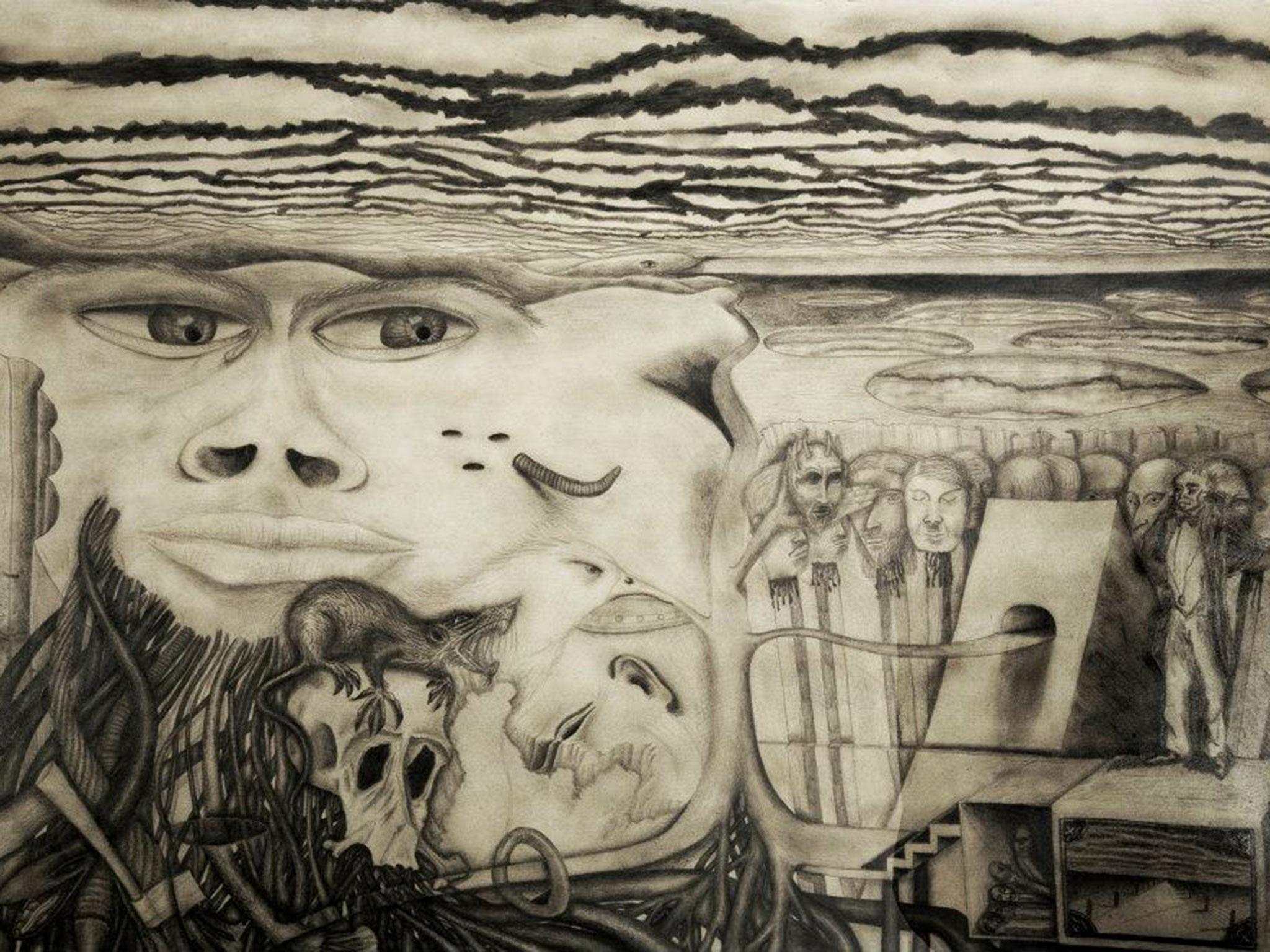

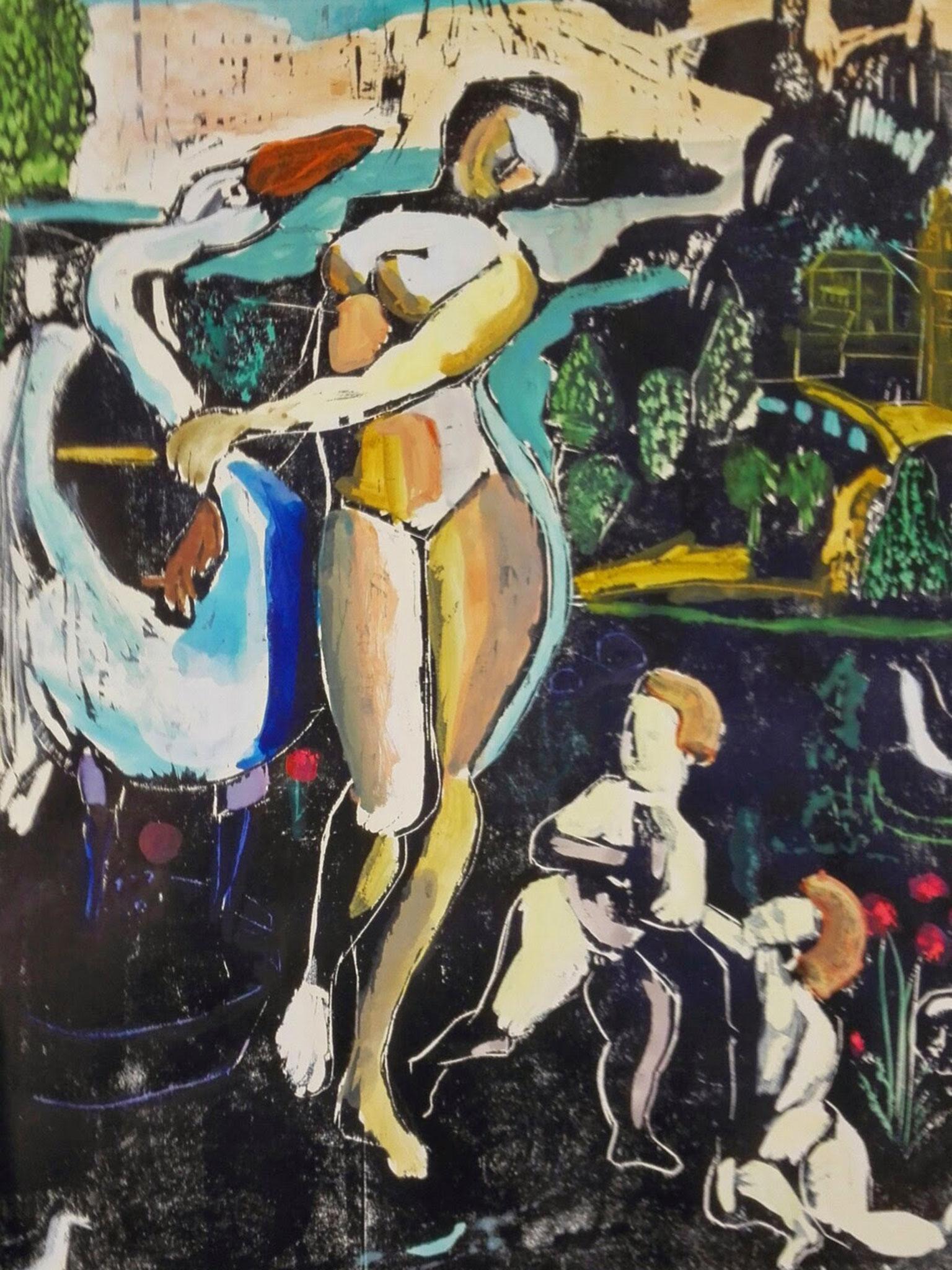

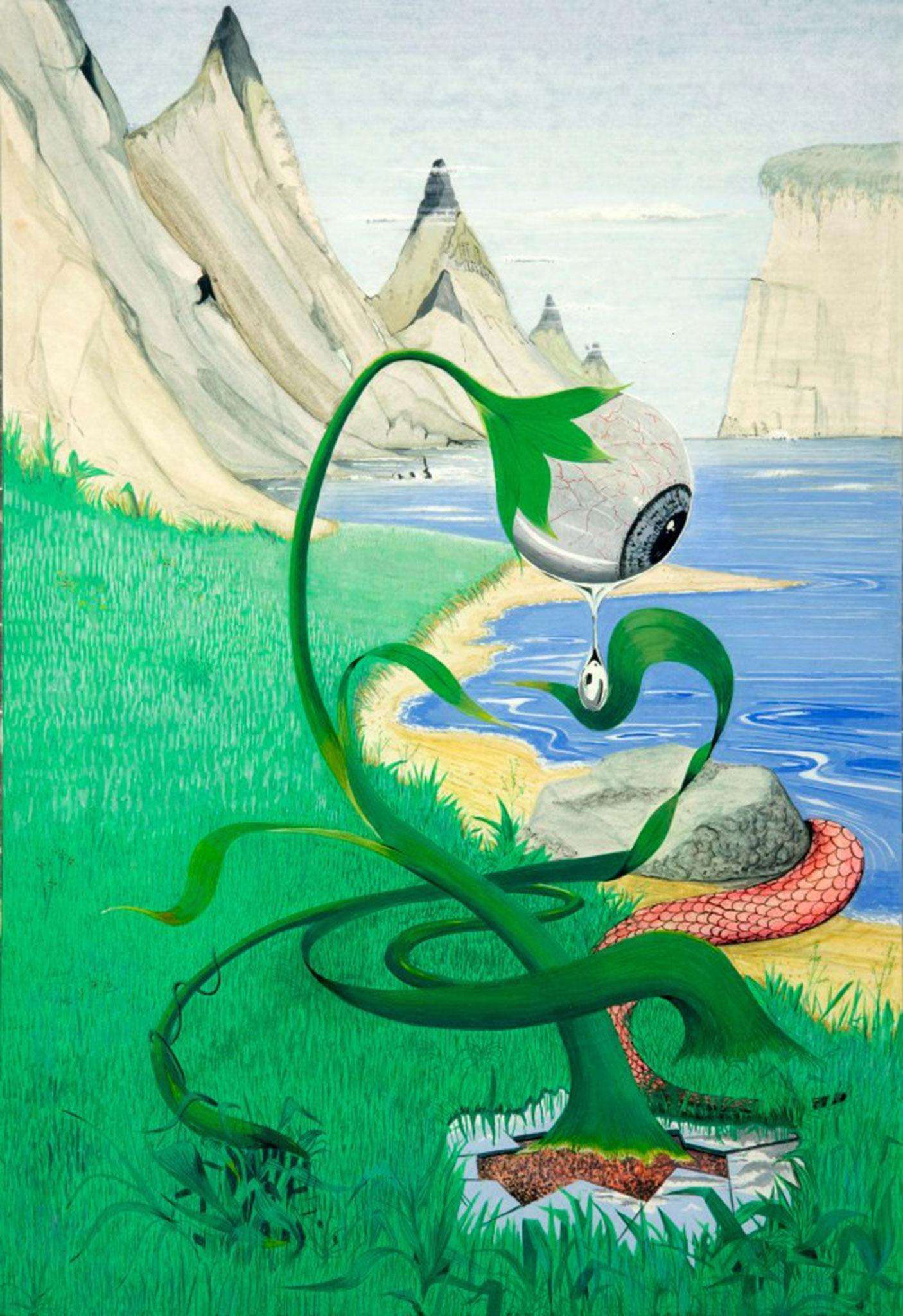

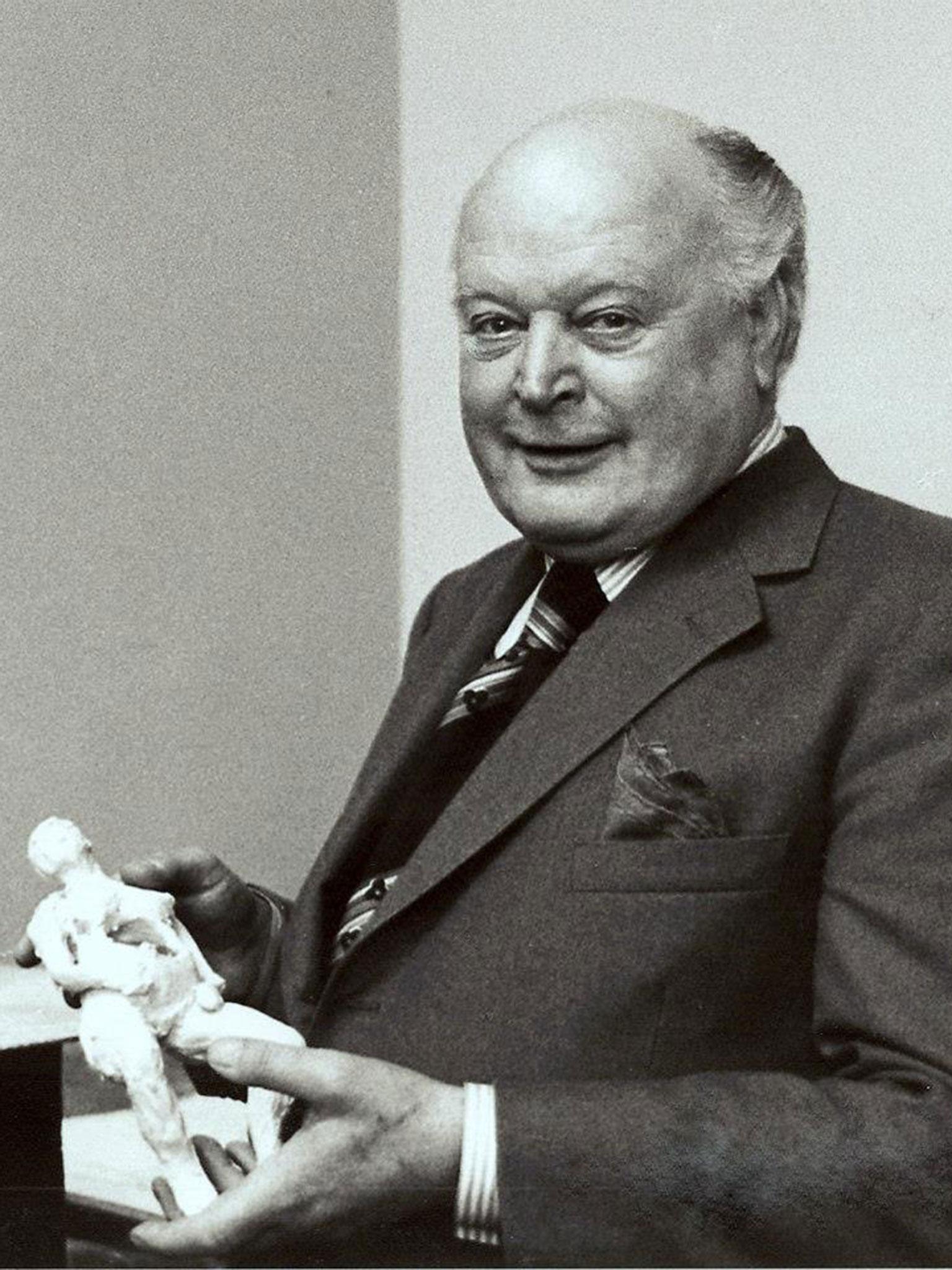

By the mid-twentieth century, asylums were being replaced by mental hospitals where patients were treated with talking and community-based therapies. It was during this period that Edward Adamson, the artist who pioneered the art therapy which affected Molloy so deeply, first started work at the Netherne psychiatric hospital in Surrey. The Adamson Collection, comprising 5,500 resulting artworks, is set to be showcased as part of the Bedlam exhibition.

A trained artist rather than a clinician, Adamson argued that the mind as well as the body should be considered in the treatment of physical ailments, and lectured on the use of paintings in tuberculosis sanatoria. As tuberculosis was tackled and sanatoria closed, the approach was adopted in mental hospitals. Adamson made his first pioneering step into mental health therapy in 1946, when the superintendent at Netherne asked him to establish regular art sessions for patients, in an echo of the theories of Swiss psychiatrist C G Jung who believed art had a healing mechanism.

“The Asylums were highly regulated places to live,” explains Dr David O’ Flynn, chair of the Adamson Collection. “Indisputably, the studio was not only a place of calm and creativity but also a place of acceptance. Adamson accepted people's behaviour and accepted the arts they wanted to make.”

Patients were given free rein in Adamson’s studio, an important outlet for those who had been trapped inside institutions for decades. Their work was interpreted as a tool for diagnosis – schizophrenic patients were believed to use red paint, for example - and the classes were organised like a controlled experiment, with each patient given the same easel and paper.

Until the Mental Health Act of 1953, those suffering from mental health conditions had no rights. As tuberculosis – another illness that led to long-term institutionalisation – was cured with medication, clinicians were hopeful that mental illness would be the next. The result was an odd mix of over-medicalisation, most startlingly in the use of lobotomies, alongside a range of social and creative therapies, explains Dr O’ Flynn. Adamson would often be faced by patients who had recently undergone unnecessary surgeries: their heads shaven and bandaged.

“Between the 1950s and 1970s, there was far less awareness given to the experience of patients and of listening to them and respecting their rights,” says Dr Jill Westwood programme convenor MA Art Psychology at Goldsmiths. “Even though Adamson's studio was a significant humanising intervention, the artwork was virtually appropriated by the 'expert' psychiatrists for the purposes of 'diagnosis' rather than that of human relational understanding.”

Nevertheless, Adamson’s studio and the work of his contemporaries were a trail-blazing force, and in 1964, Adamson became the first chair of the British Association of Art Therapists. But as he focused on the power of art to heal rather than as a tool for psychotherapy, he distanced himself from healthcare and preferred to regard the work of patients as “outsider art” – itself now a contentious term. His influence is now captured in the thousands of drawings, paintings, and sculptures of the Adamson Collection.

Decades after Adamson set up that first studio, art therapy is still evolving. The Bruce Perry Child Trauma Academy in Texas, for instance, uses art therapy treat severely neglected children, while the Matisse Trial by UK scientist is attempting to understand how it can aid those with schizophrenia, says Dr Westwood. The veterans charity Combat Stress, meanwhile, promotes art therapy in the treatment of PTSD, similarly to Art Refugee UK which uses such techniques to help refugee and migrant communities deal with trauma.

Molloy knows the power of art therapy first hand. Describing bi-polar as a balancing act in the same way that a diabetic may need to constantly monitor their illness, he says that painting and writing poetry helps him to stay in control and focus on the present. “I had these severe mood swings, and I could be manic or depressed. I think by channelling that energy into painting it brought something out of me took my mind off the thoughts of depression and extremes.”

Lisa Buttery, a 25-year-old artist who works at Brighton University, shares Molloy’s experiences. She has been dealing with borderline personality disorder since her teens, and has used art in therapy and as a creative outlet. She was referred to art therapy aged 15, where the clinician would ask her to paint or create an image to express her emotions.

“It definitely helped me on days when I didn't feel like talking and helped me to express things that I found hard to put into words,” she says.

As her condition improved, she helped to develop Art in Mind, a volunteer group for people with mental illness which created work to raise awareness of such issues and challenge stigma. “The process of that was undoubtedly therapeutic for us. We'd lay out all the materials at the start of the session and pick up what we felt like using and just do what we felt like. It helped me by belonging to and feeling accepted in the group, not feeling alone or isolated in my struggle with my mental health, and by intending to help others and taking something positive from our negative experiences.”

It is stories like these that prove Adamson had a profound and undeniable impact on healthcare, and offer a glimmer of positivity at a time when mental health is still a taboo. But, as Dr O'Flynn observes, Adamson would have been nothing without the brutalised patients.

"What I have learned from Adamson's work is that art - and more generally making of things - makes you better," says Dr O'Flynn. "The asylum patients were people and their history and their suffering should not be forgotten."

'Bedlam: The asylum and beyond' runs from 15 September to 15 January 2017 at the Wellcome Collection in London.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments