A migraine is so much more than a bad headache: hope for sufferers as cures are researched

With research into methods to help sufferers on the rise, will people finally start to understand the difference between a throbbing hangover head and an excruciating migraine?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

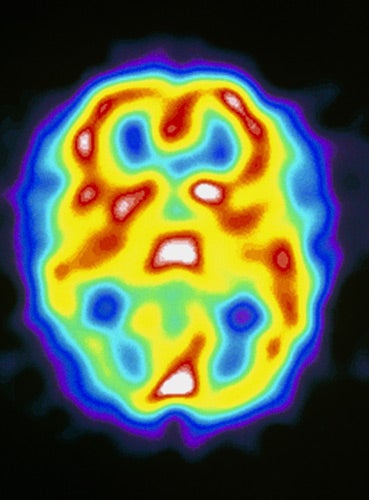

Your support makes all the difference.I knew there was a significant difference between a migraine and a headache when I was CT scanned for stroke damage and temporarily diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. It was after a severe bout of migraines erupted in a three-week period.

Sufferers or 'migraineurs' if you want to sound less debilitated, haven't got the richest wealth of medication to hand. It works on more of a trial-and-error-kill-two-birds-with-one-stone basis. Beta blockers, antidepressants and anti-epileptic medications were accidentally found to relieve the debilitating headaches, as well as triptans for acute attacks, although it is not 100 per cent clear how these work, or which ones will suit who best.

So when surgery was touted as a possible cure after plastic surgeon Dr Bahman Guyuron reported that patients who underwent facial rejuvenation procedures found that one of the side effects was migraine relief, sufferers were offered a (short lived) glimmer of hope.

Unfortunately research into the procedure has concluded that there is insufficient evidence to support such claims. Multiple flaws were found in the methods of study, surgery was deemed too risky, and the general idea behind the procedure doesn't click with what we know about the underlying causes of migraine.

Since Guyuron's research, surgeons have sought to pioneer new approaches to migraine surgery or 'nerve decompression' depending on where they believe the trigger to be – in most cases this 'trigger' is understood to be caused by the interaction of the corrugator muscle above the eyebrows, and the trigeminal nerve that runs from the brain to the mouth and face. The surgery itself sounds like something of a gruesome lobotomy. It involves either making an incision and damaging the nerve so it can no longer be stimulated, or removing segments of the corrugator muscle itself.

Dr Jud Pearson, a headache specialist at the National Migraine Centre has found that most patients who have trialled the surgery have not been relieved of migraines.

"The clinics who are doing the surgery think that this is the trigger – the rest don't think it is. Their theory was that if botox freezes muscle and you get three months of relief, then take the muscle out altogether and it will be permanent. That has not been shown to be the case."

Other research focuses on the same theory, including the recent sci-fi looking headband, Cefaly. This works by applying neurostimulation to the trigeminal nerve. An electrode is positioned on the forehead and connects to the headband. Micro-impulses stimulate the trigeminal’s nerve endings to produce a relaxing effect.

Although in its early stages, the device is thought to have been successful in reducing the frequency of migraines for around 40 per cent of sufferers so far.

Migraines affect one in seven people in the UK, and it is estimated that 190,000 people have an attack every day – a figure that is up two per cent on last year. The frequency and severity varies from person to person, but statistics show that women are three times more likely to get migraines than men – and this is not always hormone related.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has rated migraines among the 20 most incapacitating lifetime conditions, comparable to dementia and active psychosis.

Sadly, despite the vast number of sufferers and the debilitating effects, in the UK migraines are the least publicly funded of all neurological disorders. Pearson says: "Funding is pretty limited. Migraine is right up there with the other illnesses like HIV and cancer. These are huge illnesses that affect millions of people so it shows you how much of a burden migraines are on health worldwide, yet the amount of money and research plugged into it does not reflect that in any way."

It is perhaps this lack of funding, and in turn a lack of awareness, that are the culprits for the non-migraineur's belief that it's just a headache – easily banished by popping nothing more than a Sainsbury's basic paracetamol.

One of the questions Pearson's asks her patients, to determine between a tension headache and a migraine is: "Can you function?"

In short - no, if it's a migraine. For me, the pain is always excruciating and I'm always temporarily blinded or experience kaleidoscopic vision. I've had migraines where I couldn't speak – I could hear the word ‘water’ in my head but just couldn't pronounce it (Waiter? Waater? Witter?) – migraines where I've lost feeling in my hands, migraines that nearly made me pass out and migraines where I've thrown up a sea of insides.

Nausea, constipation, diahorrea and sometimes aura symptoms such as visual disturbances, numbness and or tingling that precede the headache are all normal, and some sufferers can endure the pain and aftermath for up to 72 hours after the attack. Not recognisable symptoms of your bog standard headache.

Causes are somewhat of an enigma and can range from eating chocolate, cheese or red wine, walking through the perfume counter in Debenham's, to a combination of factors coming together such as that trusty friend in the red coat, a night spent tossing and turning, skipping lunch, and an imminent thunder storm. I've had them before periods, after playing on Xbox, in the middle of the night, sunbathing on the beach and after a flight. Try working that one out.

Although the surgical approach may sound like a quack invention, so too may a one off jab and magnetic pulse headbands, it gives hope to sufferers of this poorly misunderstood illness, and if it's not a breakthrough, then at least an awareness of its severity may stop others tutting in ignorance.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments