The world is not yet ready to overcome a once-in-a-century solar superstorm, warn scientists

Impact of such a space weather event on modern technology is still not completely understood

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

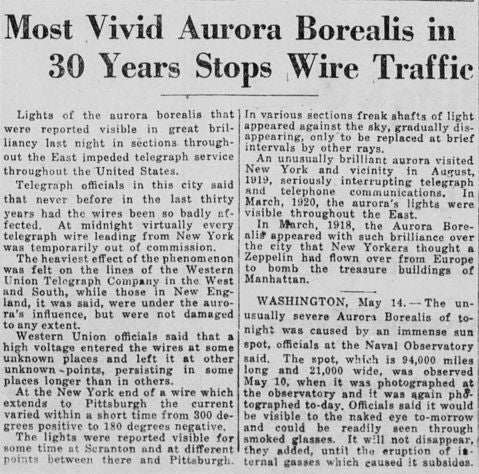

Your support makes all the difference.About 100 years ago, on May 15, 1921, multiple fires broke out in electricity and telegraph control rooms in several parts of the world, including in the US and the UK.

In New York City, it was from a switch-board at the Brewster station that quickly spread to destroy the whole building, and in Sweden, operators at Karlstad exchange first experienced equipment malfunction and faint smoke, then after a period of quiet the main fire started, leading to extensive equipment damage, studies say.

Similar reports emerged from various parts of the world, including India, the UK, and New Zealand of disturbances in electrical equipment and the then-nascent electric and telegraph wires.

These were due to magnetic fields generated on Earth by one of the biggest solar storms to have impacted the planet – known as the 1921 New York Railroad Storm.

“The effects were in terms of interference to radio communications, telegraph, and telephone systems, all of which were used in 1921,” Jeffrey Love, a Geophysicist in the Geomagnetism Program of the US Geological Survey (USGS), tells The Independent.

This space weather event is “essentially a wake-up call,” according to Dr Love, who says if such solar superflares were to strike Earth today, it could bring even more devastation.

“When we look back at this time, anything that’s related to electricity wasn’t as important in 1921 as it is today,” he says.

Scientists have understood for over a century how these solar superstorms arise and cause disruptions in electricity and communication networks. But the impact such a space weather event could cause today is still not completely understood.

Solar storms are caused when the sun gives off a burst of electrically conducting plasma in what is called a coronal mass ejection (CME).

When CMEs are directed towards the Earth, they could pass between the Sun and our planet at very high speeds of about 2000 km per second, reaching the Earth in a couple of days.

Since the plasma in the CMEs is electrically conducting, it interacts with the Earth’s magnetic field, bringing current into a layer of the Earth’s atmosphere called the ionosphere. That in turn produces a magnetic field via the principle of electromagnetism by which motors and generators work.

The process ultimately generates electric fields in the electrically conducting surface of the Earth, driving electric currents through the different types of rocks on the crust which have varying abilities to conduct current.

“Now, if you happen to have a power grid to flow across an electrically resistive geological structure, the current can’t flow very well through this part of the Earth. So, it takes the path of least resistance, which is through the power grid,” Dr Love says.

“So it ends up kind of short-circuiting this, and you get currents in your power grid system, which are unwanted or uncontrolled. And since the power grid system is all about controlling currents, and managing them, and basically, having alternating currents at a particular frequency, in this scenario, there is quasi-direct current flowing in a system designed for alternating current,” he adds.

Experts say solar superstorms can be particularly disastrous to transformers in the power grid, causing them to heat up and shut down because of the unwanted flow of current.

“And if you damage a transformer, then you might have to replace it, which means your power outage could last quite a while,” Dr Love says.

Mike Hapgood, chair of the Space Environment Impacts Expert Group (SEIEG) in the UK, also believes one of the biggest problems would be faced by the transformers in power grids since they work on very specific frequencies of alternating current around the world.

“When the current induced on the Earth by solar storms gets into a transformer, they unbalance it,” Dr Hapgood tells The Independent.

Transformers rely on the balance of currents as the voltages changes – and if they are pushed out of balance, it can cause heating, and vibration that would switch them off.

“So that’s how you can get the blackout, but you can switch it back on. There will be damage but it won’t be particularly big damage,” Dr Hapgood says.

Citing the example of a moderate-level solar storm that struck the Earth in 1989, he said the power disruptions it caused in Quebec, Canada were resolved in about nine hours.

“People now know how to fix it. And I wouldn’t expect anything extensive. While some raise fears that it would take years to resolve, I don’t think a lot of people, especially the engineers really believe that,” Dr Hapgood says.

Scientists also say satellite navigation systems could be significantly impacted by solar superstorms.

“One of the big ones coming up now is the impact on satellite navigation GNSS. I think it’s not so much that it would break, but it will have a lot of intermittency over several days. In some points, it would work, and at other points, it wouldn’t,” the space weather researcher explains.

“At some points, it would be putting people in completely the wrong place. So there’s an element of it that would not be trusted. I think for aviation, that’s not bad, because they have clever systems which actually tell pilots if they can’t be trusted,” Dr Hapgood adds.

However, experts are unsure of the extent to which global internet connectivity would be impacted by a solar storm.

According to a recent study by Sangeetha Abdu Jyothi from the University of California, Irvine, and VMware Research, the robustness of undersea internet cables to such space weather events has particularly not been tested.

The research predicts that long-distance optical fiber lines and submarine cables, which are a vital part of the global internet infrastructure, are vulnerable to CMEs.

While the optical fibers used in long-haul internet cables are themselves immune to these currents, Dr Jyothi says these cables have electrically powered repeaters at about 100 km intervals that are grounded and are susceptible to damages.

Since the repeaters in these cables are connected in series and to the ground – and also at intermediate points – these ground connections can act as entry and exit points for the induced currents, she tells The Independent.

Dr Love also believes long-distance communication cables could be particularly vulnerable.

“The long, large-scale electricity systems are grounded because you seek stability in the operation of your power grid or your telecommunication cable. And normally the earth by grounding it to the earth provides that stability, but it’s during a solar storm that it doesn’t. So that’s the kind of paradox,” says Dr Love.

“They are exposed to the magnetic storm hazard because they have these components called repeaters that are grounded. So yes, the long telecommunication cables are also vulnerable,” he explained.

However, not all space weather experts agree that the effects on the internet system could be as catastrophic.

Dr Hapgood, who advises the UK government on the impacts and mitigations for space weather, asserts that the undersea cables are by nature less conductive, and their high resistance would make them less vulnerable to the flow of disrupting currents in the event of a severe solar storm.

According to the UK scientist, an undersea cable spanning 9000 kms, made of 5 mm diameter copper wires, would carry very little current to cause problems.

Due to the large resistance offered by undersea internet cables to the flow of the geomagnetically induced currents (GICs) from solar storms, he believes there will likely not be any disturbance caused to the global internet connectivity by solar flares.

There could be a way to test these theoretical predictions, believes Dibyendu Nandi from the The Center of Excellence in Space Sciences India (CESSI) at the Indian Institutes of Science Education and Research, Kolkata.

Even though the undersea cables may be comparatively better off, Dr Nandi tells The Independent that the impact of solar storms on these cables “needs to be fully understood“ since they are a strong backbone of the global internet infrastructure.

“So, I think one intelligent way to do that would be to have instruments that can measure current surges in these undersea cables, and observe the variations of these current surges across a period of time wherein various geomagnetic storms of different scales have occured. Dr Nandi says.

According to the Indian astrophysicist, known for his studies related to Solar Magnetic Cycle, the results from such experiments can be compared to understand what kind of impacts the strongest geomagnetic storms can have on undersea cables.

The induced current is proportional to the voltage, and the electric field generated is equal to the voltage divided by the length over which the voltage is being used, he explains.

“So when you have a larger length the voltage also scales to the length. And the current is directly proportional to the voltage and the current will also be proportional to the length,” Dr Nandi adds.

Dr Jyothi concurs. She believes the induced voltage and current for the strongest storms could be much greater and may pose a threat to transocean internet cables.

“Induced voltages are a better way to express the risk. Induced voltages for the strongest storms will be around 10X compared to moderate scale storms, so the current will be in that range,” she said.Engineers measure how much voltage variation a cable can take in V/km, and submarine cables are designed to handle about 0.1V/km.

In 1989, during a moderate storm, 0.13 V/km was measured on a cable running under the Atlantic, and in 1958, during another moderate storm, 0.5 V/km was measured on another transatlantic cable.

But these are not the voltage values recorded from the strongest CMEs.

“With the strongest CMEs, 5-20V/km variations are expected. So it is orders of magnitude higher than what the cables are designed to handle,” Dr Jyothi adds.

While currently, both long distance cables and communication satellites, which are integral to the global internet infrastructure could be vulnerable to CMEs, Dr Jyothi says there are several other solutions for temporary connectivity.

“For example internet-powered drones or balloons like project Loon Google had, and there are also proposals for high altitude platform stations which are floating in the air and provide internet connectivity to larger areas. But we don’t have any solutions that can be readily deployed,” she says.

There are also proposals in the US for inserting automatic shutdown to the ground connections at some of the transformer stations that would cut off the grounding connection, if there is a surge in electricity going through that ground point.

However, for this experimental system to work as intended, Dr Love says there must be an apparatus to shut down the grounding connection at all the transformer stations simultaneously.

This is because, if the grounding connection is temporarily cut off at one point, then the electricity would simply go through a different point.

“And we’d all have to work simultaneously. So they’re experimenting with this, to see what would happen if you just did a little bit of it. And it’s still a work in progress, but it is expensive” Dr Love adds.

Experts agree that there are still no comprehensive plans to prepare for such a space weather event.

A US project, known as SWORM, organised through the White House brings together different federal agencies to try to address space global hazards.

“They are not just worried for the power grid but also about losing communication satellites since we could lose a certain fraction of the communication and GPS satellites due to solar storms, you have,” Dr Love said.

The bigger problem, according to Dr Hapgood, is finding out how all the pieces of known information fit together.

“When you’ve got to put it all back together, how does everything interact? And often the overall response is not determined by the behavior of the elements, but by the interactions between them as well,” he said.

In a recent study, Dr Hapgood and his team also caution that several scenarios following a solar superstorm may occur close together in time, with the need for government officials to prepare for the “near-simultaneous occurrence of many different problems.”

The scientists underscore the need for policy makers to consider how public behavior will play out during such severe space weather events.

Dr Jyothi agrees, adding that there is an urgent need to better quantify the risks and then design solutions based on that.

“We need better models. We know they are vulnerable but we don’t know the extent,” she added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

153Comments