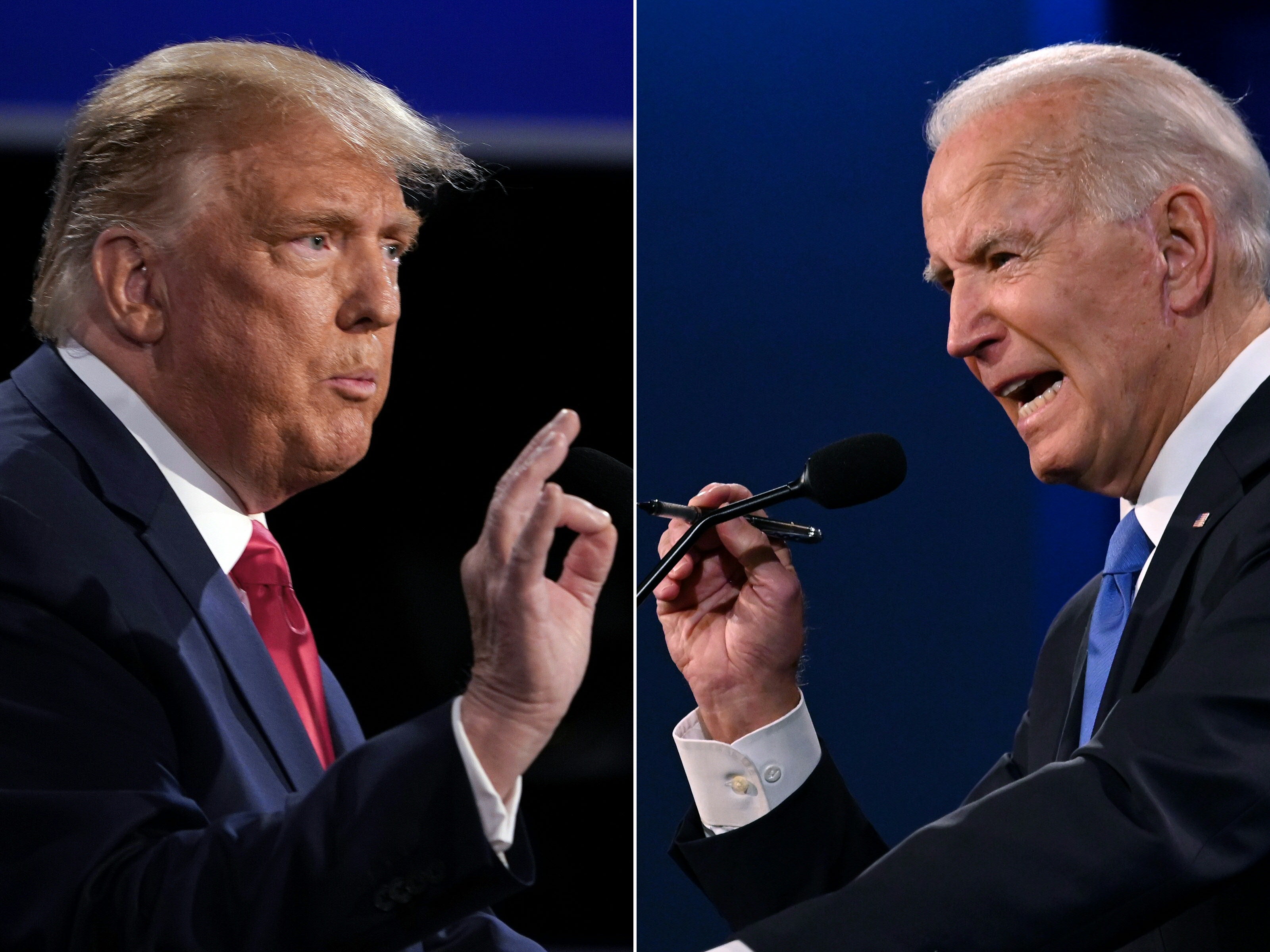

The future of Section 230: How Trump and Biden’s fight could fundamentally change the way the internet works

Wikipedia, Reddit, Yelp, and many smaller services could struggle as politicians target Facebook, Twitter, and Google

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the last few days of his presidency, one that saw the coronavirus pandemic, the possible start of World War III, and an impeachment, Donald Trump turned his attention to what may be his most important personal concern: his Twitter account.

Specifically, the outgoing president launched a final grab at legislation that would allow him revenge against social media companies that he saw as attempting to censor or undermine his posts.

That legislation, which has been irritating the president since the first infamous instance of Twitter adding labels to the president’s tweets, is Section 230.

“Weak and tired Republican ‘leadership’ will allow the bad Defense Bill to pass. Say goodbye to VITAL Section 230 termination”, the president tweeted on 29 December. “Twitter is doing nothing about all of the lies & propaganda being put out by China or the Radical Left Democrat Party”, he lamented in May, one of many attacks on the law that he has claimed is a national security threat, without evidence. “They have targeted Republicans, Conservatives & the President of the United States. Section 230 should be revoked by Congress. Until then, it will be regulated!”

In brief, Section 230 protects any website or service that hosts content – from the world’s largest companies such as Facebook and Twitter and news outlets' comment sections, to cooking forums – from being legally liable for content posted by its users. Libellous posts are thus not the responsible of the forum that hosts them, but the person who posts them.

Section 230 has been a political battlefield for some years, partly due to misrepresentation of the law conflated with the separate issue of perceived social media bias against those on the political right.

This year, Senator Lindsey Graham has levied attacks on the law in an attempt to control what tech companies can moderate, and Mitch McConnell is currently in the process of tying stimulus payment bills to full repeal of Section 230. Donald Trump may be leaving the White House, but these issues will still remain on the Republican’s agenda. But its unknown what the Democrats, and their new president, will do.

In an interview with the New York Times, then-presidential candidate Joe Biden decried Facebook’s ability to spread misinformation. “I’ve been in the view that not only should we be worrying about the concentration of power, we should be worried about the lack of privacy and them being exempt, which you’re not exempt. [The Times] can’t write something you know to be false and be exempt from being sued. But he can,” Mr Biden said, referring to Mark Zuckerberg.

Mr Biden continued to say that Section 230 should be revoked because Facebook is “propagating falsehoods they know to be false … There is no editorial impact at all on Facebook. None. None whatsoever. It’s irresponsible. It’s totally irresponsible.”

Now that Mr Biden has won the presidential election, it will be the Democrats turn to enact reform. However, whether or not Mr Biden meant exactly what he said is debatable. It has been left to journalists, tech companies, and lawmakers divine what actions may be taken.

Mr Biden’s call to scrap Section 230 is “a placeholder, a way of saying we need to have a meaningful discussion about reforming it,” Boston University law professor Danielle Citron has said.

It is a symbol for the need to address Facebook being used to cause a genocide in Myanmar or Twitter allowing Mr Trump to become the biggest source of coronavirus misinformation in the country rather than moderate his tweets as they would any other user.

Democratic congressional staffers, speaking to the New Yorker, apparently suggest that Section 230 could be left intact, but there would be exceptions (“carve-outs”) for egregious breaches of platform policy such as consumer fraud or terrorism.

Bruce Reed, an advisor to Mr Biden when he was vice president, has suggested “throwing out” Section 230 because of the “nasty, brutal, and lawless” way the internet has developed.

However, the repercussions of legislation might be more brutality. Legislation that banned unlawful sex on internet platforms simply drove sex workers into more dangerous environments, both offline with a rise in prostitution-related arrests and online towards the Dark Web.

The Biden transition team did not respond to numerous requests for comment from The Independent, and Mr Biden has not advanced a specific agenda.

For technology companies, frustration comes from uncertainty about what Section 230 changes could look like – changes that could damage parts of the internet that have both become ubiquitous, but are notably smaller than the giants of Facebook and YouTube which are oft-cited regarding these debates.

Wikipedia, Reddit, Yelp, and many others could be severely impacted depending on what form of legislation is decided.

Mr Graham’s bill, for example, aimed to narrow what content tech companies were protected from, specifically “otherwise objectionable” content that gives platforms the ability to curate their [ecosystem] as they see fit.

“That term – otherwise objectionable – is what lets a cooking forum keep politics, for example, off its platform. The Graham bill removes that “otherwise objectionable” and replaces it with “promoting self-harm, promoting terrorism, or unlawful’ [content]”, the Wikimedia Foundation’s Senior Public Policy Manager Sherwin Siy told The Independent. “[It says] here is a defined list of things for which we think it is legitimate to moderate content, otherwise you can’t."

This would mean users could submit lawsuits against a platform that removed content that was, for example, racist, but which that did not specifically violate the terms set out by this reformed version of Section 230.

For Wikipedia itself it would potentially mean implementing policies that removed the anonymous aspect of editing – or disabling certain fundamental ways the website works to protect it from liability in the event of libel. “If [Section 230] was repealed, we would be sued left and right,” Siy says.

“Wikipedia is built on the idea that anybody can edit. You don’t need to provide an email address or contact information. It will just log your IP address. That might be something that changes – the ability for anybody to edit. Yes that means you get vandalism, but the vast majority of edits from anonymous edits are good.

“You’ll see contributions from places with repressive governments – where people are targeted for their edits – and the amount of information you can get from Wikipedia about those places diminished”.

Reddit believes that, as a competitor to Twitter or Facebook, it could be crushed by reform. “On the one hand you either allow everything, you allow the worst type of content on the internet and you have to because that's the best way to avoid liability”, Benjamin Lee, of Reddit's general counsel, told Protocol, “or you avoid liability by restricting the amount of content so much that people aren't allowed to say anything actually meaningful or authentic.”

For some platforms the notion of leaving defamatory reviews up could be costly. A business that is angry about a poor review could claim the review is false and defamatory, demanding its removal.

Yelp, or any other review site without the protections of Section 230, assistant professor of cybersecurity law Jeff Kosseff explained, would be put in a position where they have to take down the review or litigate a defamation case – meaning they themselves would have to ascertain whether their user was telling the truth or not.

“Of course, Yelp probably won’t want to do that, so Yelp likely will just remove the review, regardless of the merits”, Kosseff argues, predicting in the long run that Section 230 will indeed be repealed because there is not enough consensus on how to properly reform it.

In some sense, this is because the debate around Section 230 is not a debate about the law itself, but about perceptions of the law, the internet, and what happens when so much public interaction happens in private spaces.

It touches on what is, or is not, free speech, what algorithms show to users, and content moderation – all valid concerns, but ones that are twisted to best suit the political agenda of the person that is speaking, and ones that could be addressed by other legislation rather than changing Section 230.

Republicans are more motivated by the belief that content moderators are biased. “Their objective is to say: ‘We don’t think you have enough Republicans on your content moderation staff’”, Siy told The Independent, “and that leads to a very strange sort of place where you have a government claiming it is being censored.” Democrats, meanwhile, are more concerned about the spread of misinformation, and companies’ lackluster attempts to stop it.

“There’s a lot of pseudolaw”, Mary Anne Franks, a professor at the University of Miami School of Law, also told Slate. “Something feels like law or a legal principle, so people assume it is one”.

Nowhere is this more indicative that in the inciting incident itself: Twitter’s labels. Section 230 does not protect the label on Mr Trump’s tweets, but instead protects Twitter from libel due to Mr Trump’s own content. The label itself is Twitter’s speech, protected by the First Amendment, and if the Trump administration had wanted to it could have challenged the social media company on those grounds. It did not.

One thing is almost certain: if the aim of American lawmakers is to tackle Facebook and Google, it is likely that Section 230 reform will not be adequate – simply because their size and wealth means they can afford to comply with whatever challenges are set them. Mr Zuckerberg has already condemned Twitter as an “arbiter of truth” and, in the face of questioning by congress, encouraged Section 230 reform.

Finally, perhaps most troublingly, the rest of the world is unlikely to have a say. Facebook, Twitter, Google, Reddit, Wikipedia, and many other technology companies all have their headquarters, and servers, in the US – and so the country’s laws set the standards for their billions of users elsewhere.

As such, the world will have to hold the same, simple hope that many Americans have after any election: that the upcoming administration can do better than the last.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments