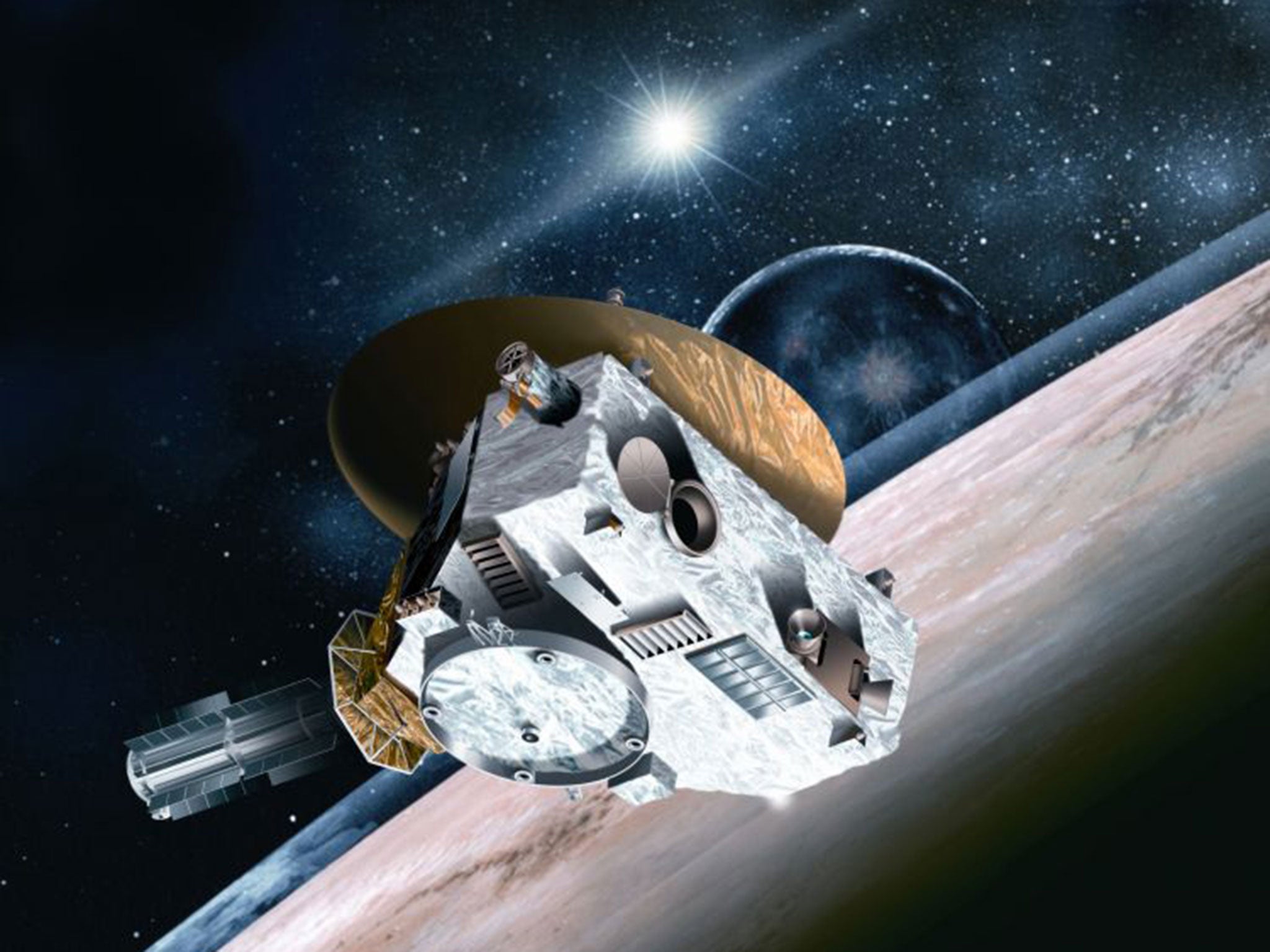

New Horizons: after Pluto flyby, scientists wait for craft to call home and tell Earth it's OK

Craft should have completed its mission, but is too busy doing science and too far away to get in touch

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nasa’s New Horizons craft should have completed its historic flyby of Pluto by now. But we won’t know whether it’s actually survived the mission until it sends back a message tonight.

The craft was on schedule to fly past the dwarf planet at 12.49pm, taking the most detailed pictures ever seen. It appears to have made the — flying slightly faster and closer than expected — but will send back its first messages at about 2am UK time.

That first call will be what's called the "PHONE_HOME downlink" — a message simply telling us that it's still around and how its health is.

Until then it will be taking images and measurements, and preparing to send them back to Earth. It will take some time from the first images to fully re-construct them, since the quality of the transmission is so low.

Even if New Horizons had started sending back messages immediately, Earth wouldn’t get them for another few hours. The craft has flown nine years and more than three billion miles away from Earth for its mission, and the messages take about 4.5 hours to make their way through space.

After the probe has whizzed past Pluto and is sending the bulk of its data back to Earth, the data will stream at an average two kilobits (2,000 bits) per second. Spacecraft communications are typically measured in bits, not bytes, one byte being equal to eight bits.

In comparison, the 4G wireless networks boast download speeds of up to six megabytes (48 megabits) per second.

Even this rate of transfer is only achieved by linking both of New Horizons' two transmitters through the American space agency Nasa's largest antennas and compressing the data set.

Nasa's Deep Space Network (DSN) has facilities in three strategic sites around the world, so signals from space can be monitored around the clock. One is at Goldstone, in California's Mojave desert, another in Canberra, Australia, and the third in Madrid, Spain.

Each DSN site has a huge 70-metre (230ft) wide dish antenna capable of tracking a spacecraft billions of miles from Earth.

But despite this super-sensitive technology, the scientists who have waited more than nine years for New Horizons to reach Pluto will have to be patient a while longer.

They do not expect to collect all the trickling data beamed back from the spacecraft's 2.1-metre (83in) diameter dish antenna until late next year.

Embedded in the data will be historic, first close-up images of the surface of Pluto captured by New Horizons' telescopic camera, the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (Lorri).

One Lorri photo, even zipped and compressed, amounts to 2.5 megabits of data. At two kilobits per second it will take nearly 21 minutes to return a single Lorri image to Earth.

Additional reporting by Press Association

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments