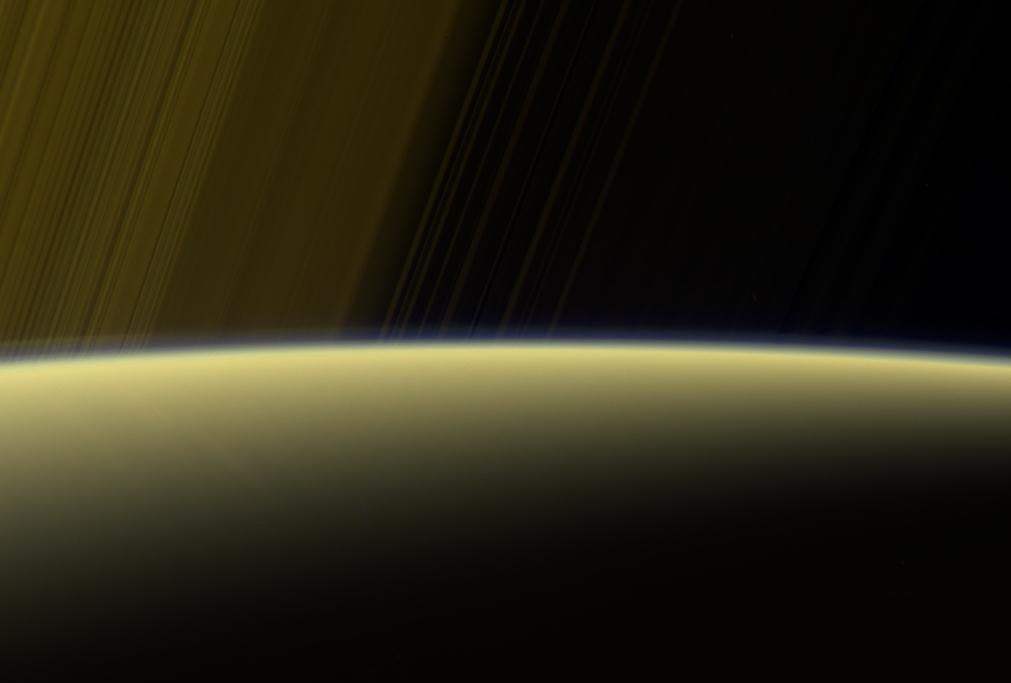

Cassini spacecraft sends back stunning images and data as it prepares to crash into Saturn

Its final days are giving us some of the most confounding data and pictures ever seen

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Cassini spacecraft is about to crash into Saturn. But before that it's sending back images and information about the planet in more detail than ever seen before.

The spacecraft is currently halfway through the final part of its long journey, which saw it fly all the way to Saturn and then explore it. During its time there it also surveyed its moons – finding information that could indicate that one is supporting life.

When that journey comes to an end, on 15 September, it will dive into Saturn's atmosphere and get destroyed. That is necessary to keep the craft from infecting any nearby places with life it could be carrying – and will bring Nasa's mission to a spectacular close.

Before that, however, the ship is still conducting important scientific work that will see it get closer to our ringed neighbour than we ever have before.

Recently, for instance, it has found that Saturn's magnetic field doesn't have any particular tilt, meaning we don't really know how long a day on Saturn is. It has also found out new information about the icy rings that surround the planet, as well as sending back stunning images of its atmosphere.

"Cassini is performing beautifully in the final leg of its long journey," said Cassini project manager Earl Maize at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "Its observations continue to surprise and delight as we squeeze out every last bit of science that we can get."

Some of the information that Cassini is finding is actually leading scientists to question what they know, rather than adding to it. "The data we are seeing from Cassini's Grand Finale are every bit as exciting as we hoped, although we are still deep in the process of working out what they are telling us about Saturn and its rings," said Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker.

That includes the strange tilting behaviour that scientists have found. It's thought that being tilted was necessary to actually generate a magnetic field – so that the currents could flow throught the liquid metal that creates them – but Saturn doesn't seem to have any such tilt.

As well as being strange on its own, that has thrown off plans to measure the wobble of the planet's interior, and allow scientists to find out exactly how long Saturn's day lasts. But that's not possible.

"The tilt seems to be much smaller than we had previously estimated and quite challenging to explain," said Michele Dougherty, Cassini magnetometer investigation lead at Imperial College, London. "We have not been able to resolve the length of day at Saturn so far, but we're still working on it."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments