Next-gen ‘neurograins’ implant could lead to better therapies for people with brain or spinal injuries

Scientists can now simulate and record neural activity using electronic brain implants known as ‘neurograins’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

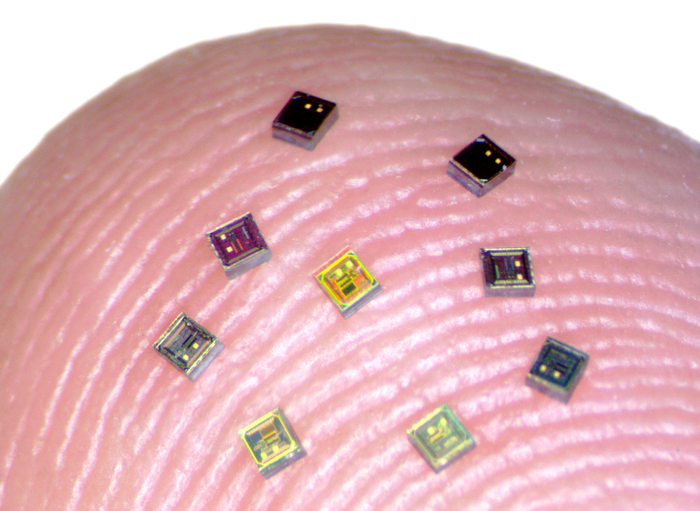

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have demonstrated that about 50 grain-sized electronic brain implants can be used to record a rodent’s neural activity, an advance that may lead to better therapeutics for people with brain or spinal injuries.

According to the researchers, including those from Brown University in the US, the sensors, dubbed “neurograins”, can independently record electrical pulses made by firing nerve cells and send these signals wirelessly to a central hub.

The scientists say the results, published in the journal Nature Electronics on Thursday, could one day enable the recording of brain signals in unprecedented detail. This can, in turn, lead to new therapies for people with brain or spinal injuries.

Most brain-computer interface (BCI) systems currently use one or two sensors to sample up to a few hundred neurons, according to researchers. Gathering data from larger groups of brain cells can, thus, reveal more insights about the functioning of the brain.

“One of the big challenges in the field of brain-computer interfaces is engineering ways of probing as many points in the brain as possible,” Arto Nurmikko, a senior author of the study from Brown University, said in a statement.

“Up to now, most BCIs have been monolithic devices – a bit like little beds of needles. Our team’s idea was to break up that monolith into tiny sensors that could be distributed across the cerebral cortex,” Nurmikko explained.

Achieving this first required shrinking the complex electronics – that detect, amplify and transmit neural signals – into the tiny silicon neurograin chips, the scientists said.

They then sought to build a device external to the body that acts as a communications hub for the implants and receives signals from the tiny chips.

In the current rodent study, the external device is a thin patch – about the size of a thumb print – that attaches to the scalp outside the skull.

This patch works like a miniature cellular phone tower, coordinating signals from the neurograins, each of which has its own network address, according to the scientists.

Using 48 neurograins placed on a rodent’s cerebral cortex – the outer layer of the brain – scientists could successfully stimulate the animal’s brain as well as record signature neural signals that are associated with spontaneous brain activity.

The researchers said the rodent’s brain limited them to 48 neurograins for this study, but added that in the current configuration of the system, it could support up to 770 such implants.

“Our hope is that we can ultimately develop a system that provides new scientific insights into the brain and new therapies that can help people affected by devastating injuries,” Nurmikko added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments