Tetris turns 30: The psychological insights that explain our love for this classic puzzler

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

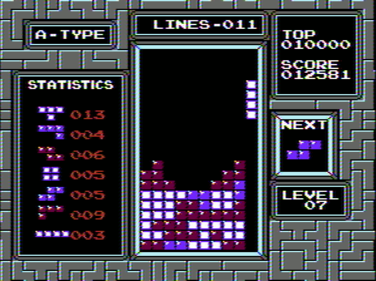

Your support makes all the difference.Tetris is 30 years old on Friday. The Soviet puzzle game was designed by Alexey Pajitnov, and shot to international recognition when it was released with the Nintendo Game Boy in 1989.

Since then it has been converted to nearly every gaming platform in existence, downloaded hundreds of millions of times for phones in the last decade, and played to death by generations of puzzle freaks.

Why is Tetris so compelling? Here's my top five reasons:

1. Instant gratification

Tetris demonstrates how immersion in a game isn't due to realism, or high-resolution graphics or surround sound. Immersion comes from the ease with which you can interact with the game world. In Tetris you press the button and get an instant response. No waiting to see what the consequences are, no delay on the reward of dropping your block to complete line. Instant gratification - "Bing!"

Research on Tetris players show that the responsiveness of the game is so good that people prefer to rotate the blocks in the game rather than mentally rotate them to figure out how they fit. The game works because it is easier to think with it than to think about it.

2. Brains love patterns

Our minds exist to find and complete patterns. This is why you see a face in clouds or a man in the moon, and why you know the third word to complete "Bacon and ....". Tetris is a simple pattern world to which you can apply your pattern completing mind. Every successful row is the result of the application of lots of tiny satisfying insights.

Our minds are so ready to be bent to the task of solving patterns that the game has become known for the "The Tetris effect", where images of falling blocks haunt players as they close their eyes and try to sleep after a long session.

3. Unfinished business

Psychologists talk about a phenomenon known as the Zeigarnik Effect, which is that our minds hang on to memories for unfinished tasks, whilst dropping memories to do with completed ones. This is something the writers of soap operas have always taken advantage of with cliff-hanger endings to each episode. The Zeigarnik effect illustrates the power of uncompleted tasks to dominate our thoughts, and Tetris takes full advantage of this - every action we take changes the terrain of the game, so that as new blocks fall from the sky, the game is one perpetually renewing uncompleted task.

4. That music

Based around a 19th- century Russian folk tune called "Korobeiniki". Here's a link in case you forgot what it sounded like.

5. Becoming a master

We like getting better at things. Even though Tetris is completely pointless, you do get better at it was practice, something which is inherently satisfying. My research uses games to try and understand wider lessons about how we can best practice to improve our skills.

So despite its simplicity, Tetris has some important lessons for psychologists. It dramatically shows how the mind is organised around patterns and goals, and can help us understand important aspects of how we learn skills.

Happy Birthday Tetris!

Tom Stafford is a Lecturer in Psychology and Cognitive Science at the University of Sheffield

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments