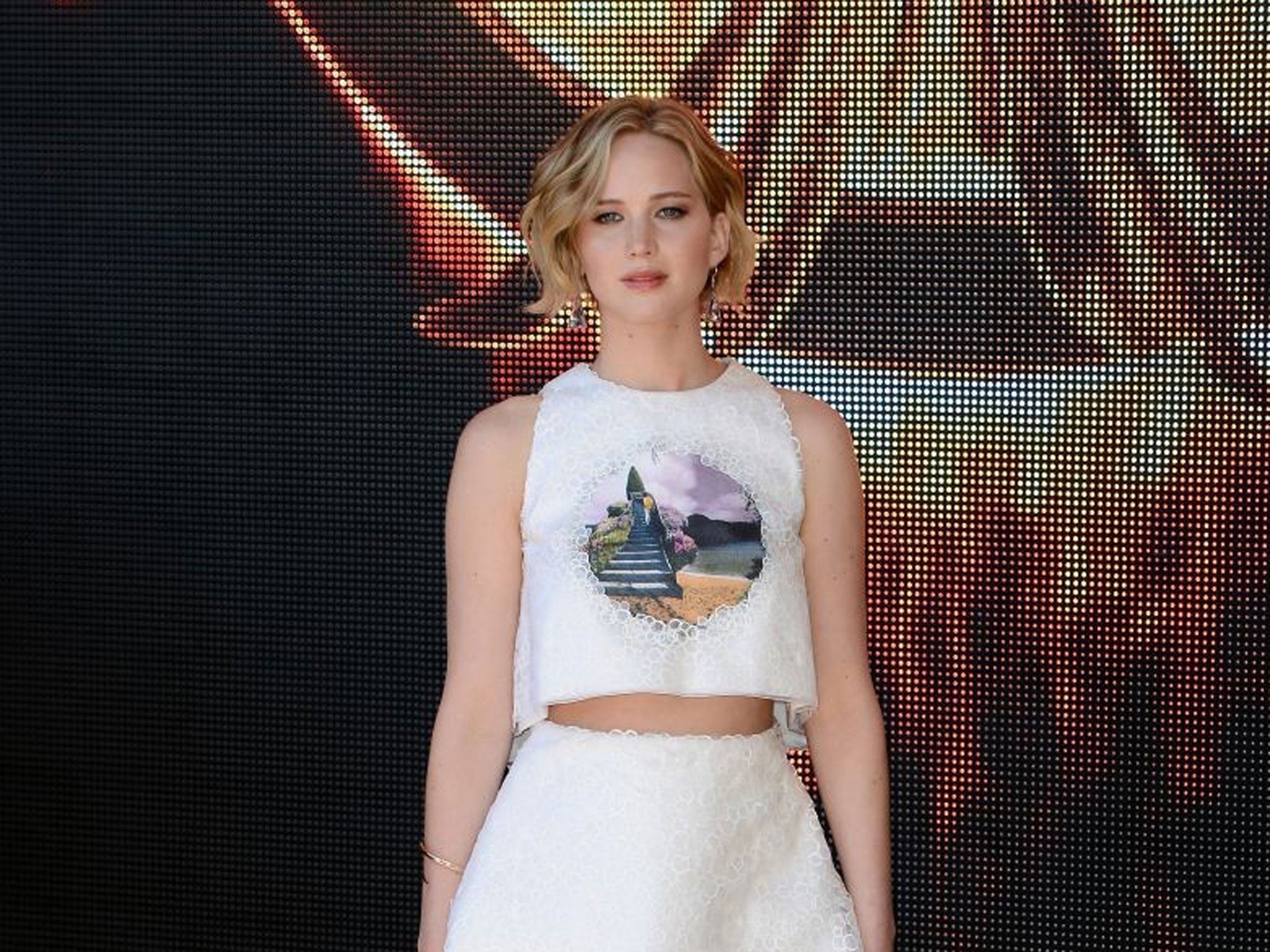

Jennifer Lawrence took on Google after its failure to remove stolen photos from its searches – but are lower-profile victims being ignored?

Threats lodged over the internet are no longer laughed off but it's often the richest, most famous, or otherwise well-connected victims who stand to benefit from this recent societal attitude adjustment, argues Amanda Hess

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In January, I published a story in Pacific Standard magazine about my experience receiving rape and death threats online, and the failure of police and technology companies to respond appropriately to threats, stalking and harassment of women on the internet.

One irony of writing the piece is that I have now become a person who law-enforcement officials and social-media employees are very eager to help out. At a panel about digital exploitation this summer, an FBI agent gave me his personal contact information, in case my stalker resurfaced; a press contact at Twitter encouraged me to forward him the abuse reports I file on the network to ensure that the site's moderators field them appropriately. Problem solved for me – and nobody else.

We are no longer in an era where threats lodged over the internet are routinely laughed off as meaningless gestures that ought to be ignored by victims, law enforcement and society at large. But a class system has emerged, one in which it's often the richest, most famous, or otherwise well-connected victims who stand to benefit from this recent societal attitude adjustment.

The tech writer Kathy Sierra is perhaps the most well-known, non-Hollywood victim of sexist online bullying, harassment and defamation, but as she writes in Wired this month, "you're probably more likely to win the lottery than to get any law-enforcement agency in the United States to take action when you are harassed online, no matter how viciously and explicitly... Unless you're a huge important celebrity. But the rules are always different for them."

Ordinary people have "a really difficult time getting law enforcement's attention" in cases of online stalking, threats and revenge porn, says Danielle Citron, a law professor at the University of Maryland who wrote Hate Crimes in Cyberspace. "Police misunderstand the law and the technology. But now, if you're powerful enough, you can make them understand: after photographs of Jennifer Lawrence and other celebrities were hacked and published online this summer, the FBI quickly announced that it was 'addressing' the 'unlawful release of material involving high-profile individuals'."

The we'll-help-if-you're-famous rule holds both for the law-enforcement agencies that investigate these threats and the tech companies that host them. It often takes a famous name, a boatload of press coverage and/or a multimillion-dollar lawsuit to encourage tech companies to remove abusive material from their platforms, even when that material clearly violates their internal policies.

Here are just a few examples of the double standard in action. On Facebook: in 2012, as Catherine Buni and Soraya Chemaly detail in The Atlantic this month, Facebook users posting in the group "Men are better than women" took an image of Icelandic woman Thorlaug Agustsdottir, doctored her face to make her appear "bloodied and bruised" and posted comments beneath it promoting domestic abuse and rape. Facebook initially told Agustsdottir that the images did not "violate Facebook's community standards on hate speech" – which ostensibly includes attacks on a person's gender – and instead constituted "controversial humour". Only after Agustsdottir took her story to the press did Facebook remove the image; only after Wired criticised Facebook's policies did Facebook publicly apologise for screwing up.

On Google: after dozens of female celebrities' private photos were published on the internet, a Google rep claimed that it "removed tens of thousands of pictures within hours of the requests being made"; the disclosure came after an attorney representing Lawrence and others threatened to sue Google for £60m for failing to act quickly enough. "The internet is used for many good things," the Google rep said. "Stealing people's private photos is not one of them." Meanwhile, as Buni and Chemaly note, revenge-porn victim and advocate, Holly Jacobs, is still awaiting similar treatment from Google after seeing the explicit photos that her ex-boyfriend allegedly posted in 2009 surface online. As she tweeted earlier this month: "Hey @google, what about my photos? #removeallvictims #endrevengeporn @EndRevengePorn."

On Twitter: after Robin Williams' daughter Zelda was hounded by Twitter harassers publishing gruesome photos of a dead man who resembled her father this summer, Twitter worked quickly to remove the photographs from its platform and suspend the responsible users. The incident later inspired a rare public comment from Twitter, which pledged to improve its policies around harassment and abuse.

When it comes to lower-profile victims, it takes a village to catch Twitter's eye. When a book blogger, Ed Champion, bombarded the novelist Porochista Khakpour with sexist threats last month, Khakpour credited a feminist "radical army" for assembling to pressure Twitter to swiftly suspend Champion's account. "The whole thing was very mysterious," Khakpour told me. On the night the harassment unfolded, Khakpour was, understandably, not immediately capable of filing a report to Twitter on the basis of its policy outlawing targeted abuse and harassment on the network. (And no matter how quickly they're filed, Twitter often takes days to respond to these complaints.) When friends and supporters filed reports on Khakpour's behalf, they were told that, per Twitter policy, only Khakpour herself was authorised to report the victimisation. Then, a user Khakpour does not know personally heard about her story and mined her contacts until she reached a Twitter employee directly to report the harassment. "Voila," Khakpour says. Champion's account was suspended and the offending tweets were removed.

The outsized attention afforded to high-profile cases has its benefits. Buni and Chemaly report that since Agustsdottir's situation made headlines – and after a sustained campaign by feminist activists, including Chemaly herself, put pressure on advertisers to compel Facebook to change its practices – Facebook has since worked openly with activists, including Citron, to help steer action inside the network. "Controversial humour" is no longer floated as an excuse for hate speech. And celebrity victims have been instrumental in spurring policy change, as when the 1989 stalking and murder of actress Rebecca Schaeffer helped inspire anti-stalking laws in California that have since spread across the US. This month, Lawrence dipped her toe into advocating for better laws to criminalise the non-consensual publication of sexual images and Citron is hopeful that the participation of celebrities like her could be instrumental in both crafting laws and encouraging better enforcement of online crimes for everyone.

"We'll never have perfect enforcement," Citron tells me. "Gwyneth Paltrow will always have her stalker [dealt with] easier than a regular woman will." But every high-profile case can help online platforms and law-enforcement agencies to better understand the issue and hopefully take it more seriously. The special treatment afforded the famous and well-connected cases should, at least, banish the persistent claim that women should not make a fuss about the abuse they receive online. It's now clear that only when victims make news do they stand to get justice.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments