Everything you need to know about the undersea cables that power your internet - and why they're at risk of breaking

There is a huge system of fibre-optic cables lying underneath the world's oceans

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Russians submarines and spy ships are "aggressively operating" near the undersea cables that are the backbone of the global Internet — worrying some U.S. intelligence and military officials who fear the Russians may sabotage them if a conflict arises, the New York Times reports.

For all the talk about the "cloud," practically all of the data shooting around the world actually relies on a series of tubes to get around -- a massive system of fibre-optic cables lying deep underneath the oceans.

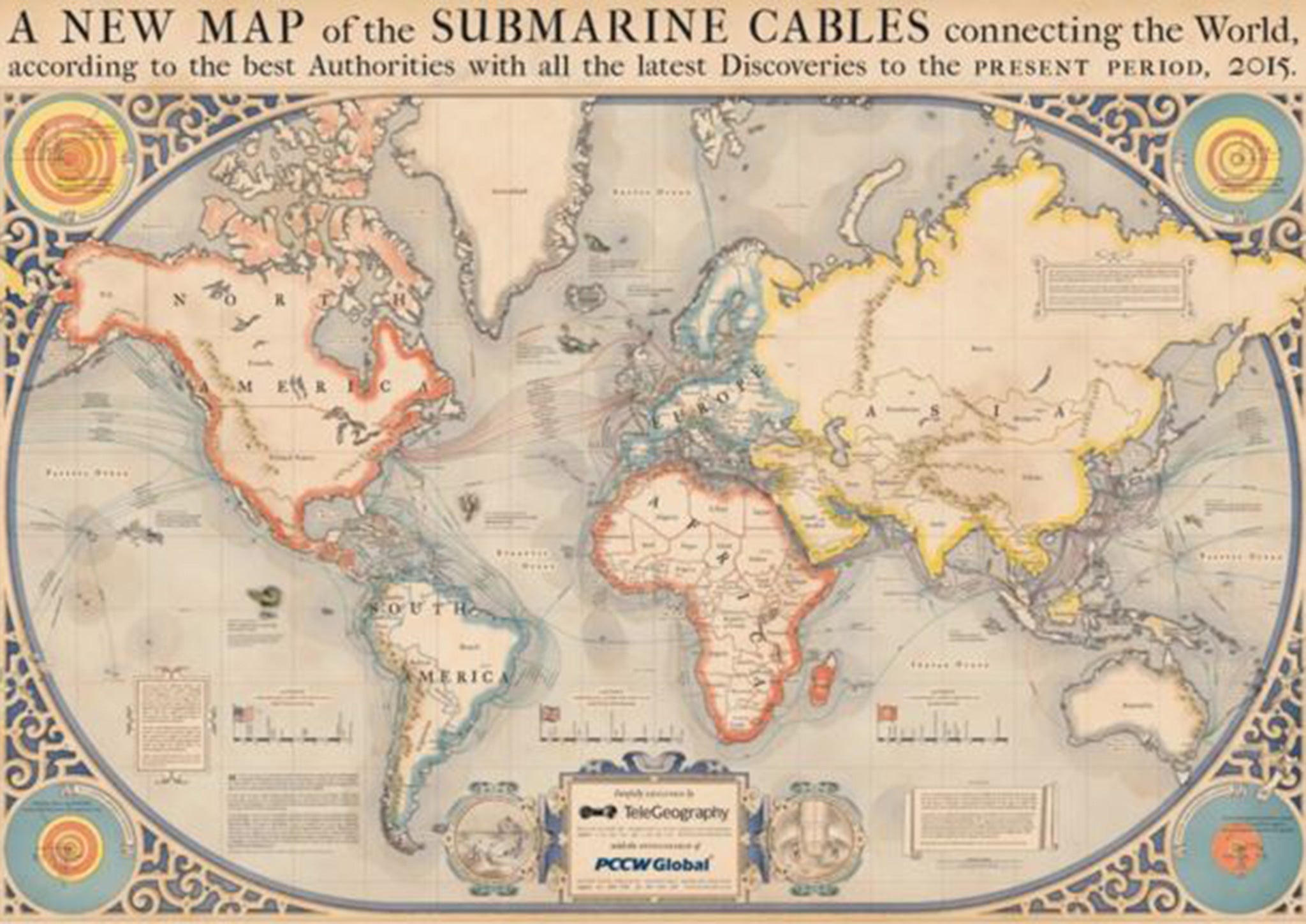

The network connects every continent other than Antarctica, carrying e-mails, photos, videos and emoji around the globe. Here's what that looks like in the style of a vintage maritime map, courtesy of TeleGeography:

How did we get here?

The modern system of undersea cables has its roots in the telegraph. The first transatlantic communications cable was completed in the summer of 1858, running under the ocean between Ireland and Newfoundland. The first "official," non-test message was sent from Queen Victoria to President James Buchanan — and it was hardly instantaneous: The 509-letter message took 17 hours and 40 minutes to transmit across the Atlantic. But that was significantly faster than waiting for a ship to traverse the ocean.

That cable took four years to build and lasted for less than a month. It took another six years before another line was set up so telegraph messages could cross the Atlantic again. But it proved that the concept could work, and over time a web of such cables spread underneath the world's oceans.

Telephone cables later joined the telegraph cables and eventually the fibre-optic cables that the Internet relies on today made it to the ocean floor.

Just how big is this network?

TeleGeography lists nearly 350 cables — some cross oceans, others follow coasts down along continents. The whole network of submarine cables spans more than 550,00 miles, with some being buried as far underwater as Mount Everest towers above ground.

How are they laid?

The cables connect to "landing stations" along the seaboard. Massive cable-laying ships go on voyages to lay the fibre along the ocean floor —plowing across the sea floor to bury the cables. Naturally, their courses are plotted to run along flat seabed as much as possible, avoiding coral reefs and ship wrecks as well the deep trenches or undersea mountains.

Historically, undersea cables were paid for by telecom consortiums. But in recent years, tech companies like Google and Microsoft started getting in on the game, putting big bucks behind the infrastructure that's made the shift to an always connected world possible.

What do the cables actually look like?

On the inside, they have a core made of layers of fibre and wires covered in a protective layer to keep the ocean out.

The cables are are several inches thick when they are near shore -- around the width of a soda can. At the deepest levels of the ocean, they are thinner, around the size of a quarter. That difference in size is because the cables actually face more threats in shallow waters, including everything from fishing ships to sharks.

Sharks?

Yes. It's not clear why, but sharks keep biting undersea cables. As far back as 1987, the New York Times reported that sharks had "shown an inexplicable taste for the new fibre-optic cables" that were being strung under the oceans. Here's how a 2009 report commissioned by the United Nations Environment Programme and the International Cable Protection Committee put it:

Fish, including sharks, have a long history of biting cables as identified from teeth embedded in cable sheathings. Barracuda, shallow- and deep-water sharks and others have been identified as causes of cable failure. Bites tend to penetrate the cable insulation, allowing the power conductor to ground with seawater.

But cable-layers have adapted: The cables Google is helping build feature a kevlar-like protective layer to fend off the toothy sea creatures.

What about other threats?

Human error is a major factor. In more than one case, an errant anchor has disrupted submarine cables — an issue that can be particularly difficult for developing nations that may have few links to the global Internet. In 2012, two separate shipping incidents severed cables linking East Africa to the Middle East and Europe within the span of a month, according to the Wall Street Journal. The incidents caused major telecommunications outages in at least nine countries.

When even accidents can cause major problems, it's understandable that government officials might fear actual attacks — especially given how reliant many functions of our modern economy are on near-instantaneous communication.

But the United States has a long history of using undersea cables for its own tactical advantage — albeit through espionage rather than destruction.

Back in the Cold War, the National Security Agency ran an operation dubbed "Ivy Bells" that tapped into communications links between two Soviet naval bases off of Russia's eastern coast. The project, which used submarines and waterproof recording pods that divers would return to gather every few weeks, ended in 1981 when an NSA employee sold information about it to Soviet intelligence officials.

In more recent years, documents from former government contractor Edward Snowden suggested that the spy agency was accessing data from undersea fibre-optic cables as part of its global surveillance efforts.

Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments