What we can learn from the (often gruesome) history of food in hospitals and prisons

What would you prefer: spleen diet, fish custard, or a modern prison meal?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

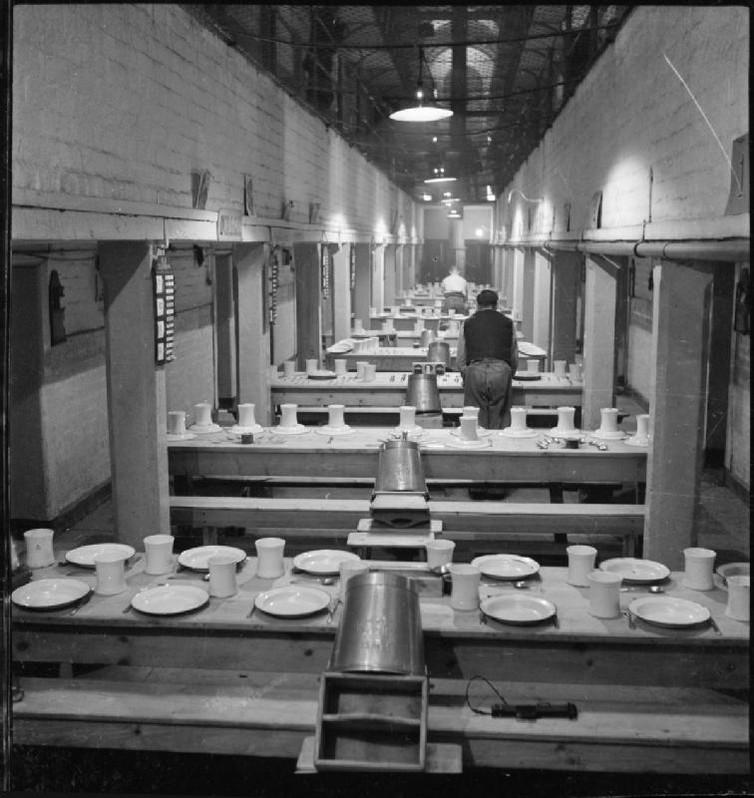

Your support makes all the difference.In the popular series Orange is the New Black (OITNB), food has often emerged as a theme: there are menus for religious diets, food to control prisoner behaviour – and even the baking of phallic goods (a penis cookie). The series brings to a general audience the problem of food provision in an institutional setting, a topic the average viewer is likely only to have experienced at school or during a brief hospital stay.

Comparing diet in different institutions may not seem important at first glance. Prisons, schools and hospitals are fundamentally different spaces, catering to populations of different sizes, ages and needs. But comparisons between hospital and prison food, specifically, have been regularly made by tabloid newspapers since at least 1945. The Sun, for example, questioned why “jailed criminals are fed better than sick hospital patients” in 2013. Despite never receiving rigorous study, this comparison reveals a deep-set assumption that some people in the care of the state might deserve a healthier diet than others.

Looking back, we can see how assumptions about prison and hospital diet have changed over time. A typical daily diet in a 19th-century English prison included a small portion of bread, meat, a pint of gruel and – less frequently – a portion of cheese, potatoes or soup. Given this, prison regulations in the 19th century allowed prisoners to complain to the prison administration about the diet provided. But repeated complaints of a frivolous or groundless nature could result in punishment – which would most likely – and ironically – have resulted in a decrease in diet. This is a punishment also passed out in OITNB, by the prison guards but also informally by inmates who run the prison canteen.

Despite periodic reforms to prison food during the century, culminating in a standard national prison diet in 1878, complaints about what ended up on prisoners’ plates persisted. Prisoners’ narratives reveal that the low quality, insufficiency and inability to make decisions about their daily routine was a great source of frustration and anxiety.

Looking at historical hospital dishes may likewise raise the eyebrows of contemporary food critics. The Lothian Health Archive has found that in the 1920s, the “spleen diet” was offered to patients, involving “pulp scraped from the fibrous part of the spleen, tossed in oatmeal and fried”. And a recipe for “fish custard” was discovered in the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh archive.

These dishes may not appeal to contemporary tastes – and certainly diet in NHS hospitals, like in prisons, has long been a subject of complaint. In 1954, the Manchester Guardian published a letter from a schoolboy writing that hospital food was “orable” (horrible). In 1972, inspectors from the Egon Ronay food monitoring group visited 31 hospitals and found that many meals were of a “scandalously low standard”. At the same time, the inspectors also found delicious and nutritious food available elsewhere.

Food varied not only across regions, but also according to the type of patient, who had different nutritional requirements. More controversially, in the 1970s some hospitals also provided different food in canteens for different types of staff. Junior staff believed that some dining rooms even had table service and tried to sneak in to those reserved for consultants or sisters. In other hospitals, particularly smaller ones, all staff would dine together.

Lucky dip

This kind of variation continues today at the local level in hospitals and in prisons. The Stoke Mandeville Hospital uses data from patient surveys and holds staff tastings to update their patient menus monthly. By contrast, the Campaign for Better Hospital Food publishes photos sent by patients who are less impressed by contemporary hospital diet. The group’s Flickr page shows examples of “mystery meat” and plates entirely filled by beige food, as well as examples of excellence.

The quality of hospital and prison food have varied across place and time for many reasons. The NHS and prison system are vast and complex. They serve large populations – which have increased over time. There were 15.5m admissions to NHS inpatient care in 2013-4. The UK prison population is about 85,000. Hospitals and prisons have different management structures and governing bodies – and populations with a variety of dietary requirements. So one key challenge for policymakers and reformers is deciding whether – and how – institutional diet should be managed, provided and controlled at a local or at a national level.

Hospitals and prison caterings also have to adhere to strict budgets. The average NHS hospital food budget is £10.75 per inpatient per day. The average prison food budget is as low as £2.02.

Taking the long view

Lessons from history can help caterers in large institutions face continuing challenges. History suggests that individual, local campaigns have made a difference to providing quality food in prisons and hospitals, despite multiple constraints. From 1931, the Home Office required all prisons to inmates of all classes a portion of plum pudding on Christmas day. This was the result of numerous offers in preceding years from reform organisations and concerned individuals who wanted to provide inmates with special food at this time.

The key questions are about how to ensure that local examples of excellence can be adopted across these large systems. The Campaign for Better Hospital Food argues that only stricter legal standards and enforcement can bring about improvement. But another method to drive improvement may be to provide further funding to enable these small-scale local pilot schemes to expand.

Cultural and attitudinal change is also important. At present, by funding food improvement or self-catering schemes in prisons, legislators may face criticism from factions of the media which already bemoans the money spent on prisoners’ food.

Changing institutional diet is challenging – but the possible rewards are great. Improving institutional diet could have positive implications for population health. Improved hospital and prison food will not only improve the diets of patients and prisoners, but also of the large workforces of these institutions. This is not insignificant: the NHS is the fifth-largest workforce in the world. Furthermore, well-fed patients and prisoners, particularly those who stay in these sites for a significant amount of time, may also institute healthier practices of eating and cooking when they return to the community.

Bringing change to large institutions is difficult, but has huge potential impacts. Something to muse on, perhaps, as we binge-watch OITNB and see how prison food continues to be shaped by – and drives – social relations, inmate health and the everyday power dynamics at Litchfield Penitentiary.

Jennifer Crane and Margaret Charleroy are research fellows in the history of medicine at the University of Warwick. This article was originally published on The Conversation (www.theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments