The apple’s enduring sphere of influence

The apple harvest approaches. With a new book out on trees, their champion celebrates the special place of the fruit in art and (particularly British) culture

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The apple tree is the arboreal alpha – always there at the beginning. Western culture begins with the apple – whether the Garden of Eden or Ancient Greece. In Genesis, the tree is not actually specified, but Renaissance painters and poets were in no doubt. Milton imagined the Satanic serpent winding up “the mossy trunk” of the Tree of Knowledge, “to satisfy the sharp desire . . . of tasting those fair apples”, while in the arresting compositions of Durer or Cranach, Titian or Rubens, the apple tree stands upright between the first man and woman, hung with irresistible orbs. But why?

If you see a mature tree in September, branches bent earthward with the weight of new fruit, flushed with fresh colour, smooth-skinned, plump and dimpled, peeping from the strong-veined, leathery leaves like a vibrant decolletage, you can begin to guess. And those low-growing branches make the forbidden fruit so very easy to reach. The tree of beginnings, it is also the tree of temptation, and it gets the blame when everything goes pear-shaped. In the Song of Solomon, it is the most desirable tree in the wood, the nest and larder of lovers, whose very breath is apple-scented. For the Greeks, it was the tree of love and discord, because when faced with the difficult task of choosing between three goddesses all regarding the golden apple as theirs by right, Paris decided that it should go to Aphrodite. The revenge of the rejects, Hera and Athena, rapidly spiralled into an all-consuming conflict, as Paris gained Helen but lost all else in the Trojan War.

The apple tree fosters love and hatred, its fruit generally growing with one fat cheek glowing red in the warm breath of the late summer sun; and the other, pressed against the rough branch, left pale and green. It is both the close-bosom friend of the maturing sun, loading its branches with blessings, and the poison fruit. Something about the tree with the perfect, palm-sized spheres prompts deep emotions, as we learn early from Snow White. Under the lovely, shiny red surface, we sometimes find wormholes, earwigs and a core completely rotten: not every new bite is as sweet as its promise.

A falling apple might seem to mark the end of burgeoning beauty, the moment of fullness, but often it is really the beginning. When Isaac Newton abandoned his studies at Cambridge in 1665, because of the outbreak of the Plague, he found himself back on the family farm in Lincolnshire. The heavy crop of apples in the orchard was part of the season’s pattern, but this year he saw it in a new light. Why did apples fall down towards the ground? Why not spin up into the sky or sideways across the field? For the brilliant young mathematician, a peaceful hour under the apple tree was a moment of revelation and revolution. This was the Tree of Knowledge and a fortunate Fall, for suddenly the movement of the whole solar system was visible.

The apple’s place as the Tree of Knowledge was reinforced when the rainbow silhouette of an apple with a single leaf became the iconic sign of the first personal computers, linking the age of the gigabyte to the great Newtonian revolution in science. It has also been read as a tribute to Alan Turing, the code-breaker and computing pioneer, whose suicide in 1954 was induced by the intolerable pressures of being gay at a time when it was still illegal in the UK. When his body was found, it was lying beside a poisoned apple, half eaten like Snow White’s.

The logo may have owed something to the youth revolution of the 1960s, too, since Steve Jobs was 13 when his favourite band launched their Apple record label, its own symbol a Granny Smith. And Beatles fans were so ready to free their minds that they flocked into the new psychedelic Apple Boutique in Baker Street, demonstrating the flaw in the business model by failing to pay for most of what they found there.

In the mythic land of eternal youth, everyone lived on apples, at least according to the ancient Celts. This was the fruit that flourished in the island of Avalon, which Tennyson imagined, “Deep- meadow’d, happy, fair with orchard- lawns”, a haven where the dying King Arthur might be healed of his grievous wound. For the Vikings, too, the powerful gods depended on the lovely apples of the goddess Idun to ward off old age and mortality. And the apple tree’s long-standing association with youth may have something to do with its relatively short lifespan. Unlike the oak or the yew, apple trees seldom live for more than 30 years, being prone to unfortunate complaints such as apple canker and scab. Even a healthy tree has brown, stubby bark, with branches striking odd angles: all the goodness seems to go into the rosy-cheeked fruit.

As apple trees generally flourish and fall so fast, we might assume that they are quick to multiply. In fact, few apple trees are grown from seed because, being heterozygous, the saplings will generally turn out differently from the parent – as I discovered in a formative horticultural experiment, when, after planting some pips with great enthusiasm, I watched them grow first into pretty little seedlings before changing gradually into stunted, twisted parodies of trees. One did survive into maturity, but it was never the upright, fruitful tree that I had hoped to see.

More experienced growers know that apple trees are best produced by cutting scions – or small twigs – from a healthy tree and grafting them onto rootstock. By crossing different varieties, new kinds of apple can be bred and bred again. The remarkable apple tree belonging to Paul Barnett hit the news in 2013 because it displayed 250 different apple varieties, all carefully grafted onto its hospitable branches. The astonishingly bushy canopy, brim-full of bright fruit and little, fluttering pennants labelling each kind, is almost too much for the trunk, so every branch has its own supporting stick, creating a strange, angular, under-shadow of the exuberant tree.

Far from being an unchanging part of British culture, apple trees have been subject to perpetual modifications of one sort or another – the old ribbed costards that Shakespeare enjoyed had more or less become extinct by the time Richard Cox retired from his brewing business in 1820 to concentrate on apple cultivation at his estate near Slough. As is the fate of most famous apple trees, the original source of Cox’s Orange Pippin blew down in 1911, but by then the demand for these delicious dessert apples was such that there were plenty of flourishing descendants. A display of different apple varieties can be quite a family gathering: the Sturmer Pippin was probably the offspring of the Ribston Pippin and a nonpareil.

Apple-growing is a levelling pursuit, flourishing alike in cottage gardens and great estates: the Blenheim Orange, despite its grand name, was first raised by an Oxfordshire labourer. Where else but in an orchard might you find a grenadier, the Duke of Devonshire, Lord Lambourne, Lord Burghley and the Prince of Wales cheek to cheek with Annie Elizabeth, William Crump, Reverend Wilkes and Granny Smith?

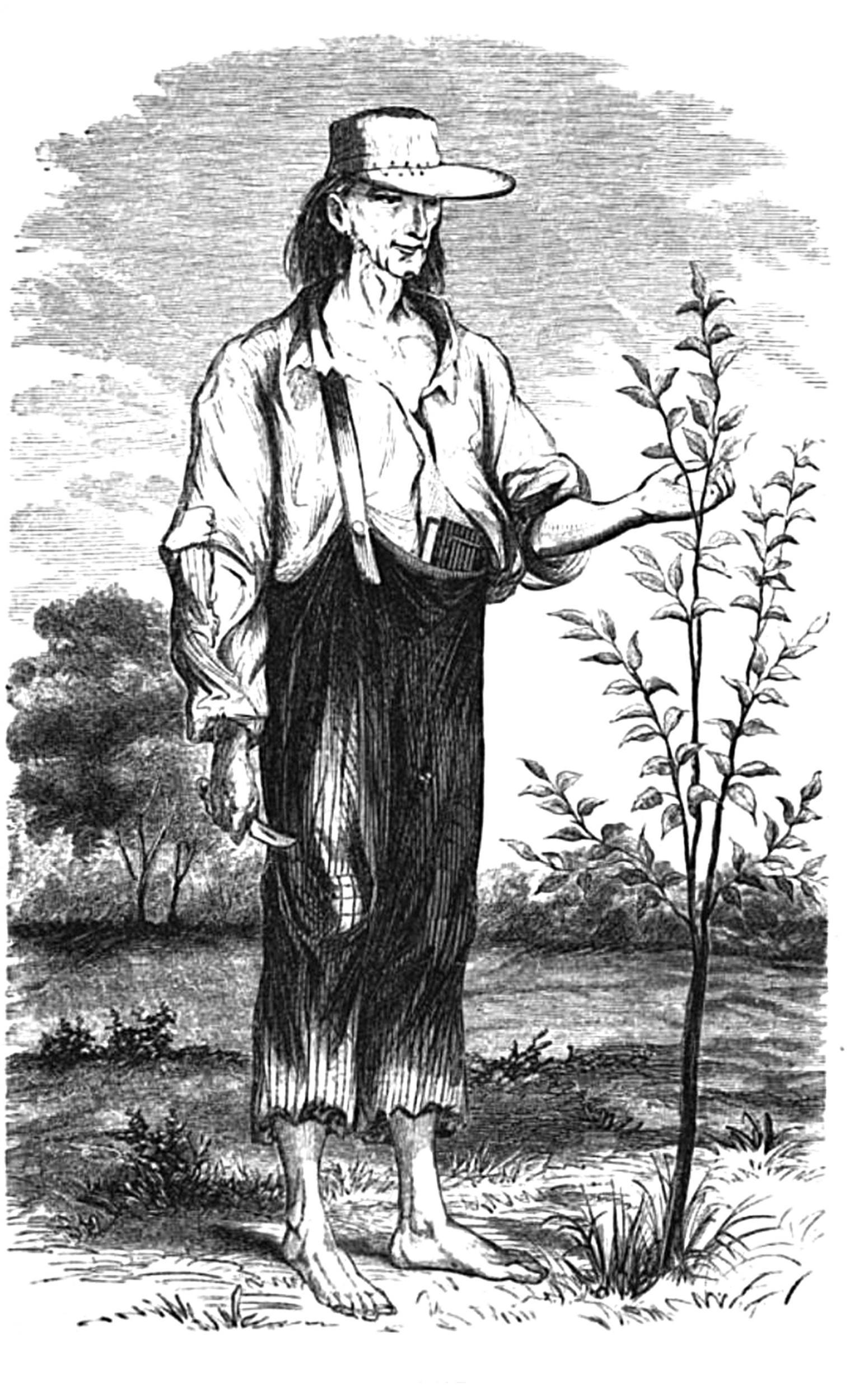

For all this clever cultivation, there have always been lucky finds, too – Bess Pool is named after an innkeeper’s daughter, who discovered the seedling in the woods one day. Apple history is full of hard graft and happenstance – but it usually involves someone spotting the potential in a humble young tree. So there is really nothing very natural about apple trees. Even their mature silhouettes are often man-made. People like to “train” them, as if, with a bit of patience, they might learn a trick or two. And they do. Under the care of skilful hands, these trees can be encouraged to assume the most surprising shapes – pyramids or wine glasses, chevrons or peacock-tails. An espalier tree, with its branches stretched out to form a great green see-saw, takes its name from the “shoulder”, because that is where the oversized limbs need most support. These carefully trained habits are not purely whimsical: they make picking easier, ensure that the fruit grows more evenly and help each apple soak up the sunrays for all-over colour.

Apples have always been a basic, affordable food, whether eaten straight from the tree or baked in pies, puffs, ambers and dumplings. Even bitter crab-apples, the fruit of the beautiful, native, wild apple tree, are a seasonal bonus, because they can be made into jelly to accompany meat. Memories of coming home from school in late September are sticky in the mind with the smell of jelly-making and my mother boiling ripe crab-apples, before straining the thick, dark, pink, viscose pulp very slowly through a makeshift jelly bag, formed from an old pillow case firmly suspended from the legs of an upturned bentwood chair. Apples are rich in pectin, the vegetarian’s favourite source of gelling agent, so crab-apple pulp sets easily into jars of translucent, sunset-coloured jelly. Apple pectin will also help set plums, blackberries and green tomatoes into jams and chutneys.

The healthy, life-sustaining apple may seem quintessentially English, but the trees with the edible fruit only arrived with the Romans. Apples are foundational to American identity, too; think of motherhood and apple pie. We now know from tracing the apple genome, however, that the ancestor of all domestic trees originated in the Tian Shan mountains, on the borders of China and Kazakhstan. The name of the capital of Kazakhstan, Almaty, means “city of apples”, and the ancient wild orchards on the surrounding slopes may soon be a World Heritage site.

Changing tastes and commercial pressures mean that many of the old, colourfully named varieties have more or less disappeared from the United Kingdom, but efforts are being made to preserve traditional orchards. London may not seem the likeliest venue for apple initiatives, but in October 1990 it hosted the very first Apple Day. For a few heady hours, Covent Garden was reclaimed by the charity Common Ground – and now Apple Day is the new-age St George’s Day, with people from across the political and social spectrum meeting annually over apple pie and cider.

Children already associate apples with IT, but with the help of the tree’s electronic namesake, they can see the apple pickers of Kashmir or Chile and think about the kind of labour that went into the neat shiny six-pack on the supermarket shelf. But it is much easier to grasp that the fruit in the fridge comes from a real orchard once you have seen them growing. You can tell when an apple is ready to pick by giving it a gentle twist: if it is already ripe, the stalk will just give way, freeing the apple to rest in your hand. Unless harvested at the right moment, apples come plummeting down like cricket balls, bruising as they land. Often they will lie hidden in the long grass, waiting quietly until someone feels that tell-tale, mushy-brown squish underfoot.

Camille Pissarro painted the apple trees of Picardy again and again, as awed by their transfiguration in spring as by their summer richness or bare winter silhouettes. The white, cotton chemise of the spring goes just as well with the overall mood as the dappled apricot and pan-tile colours of the warm autumn. Pissarro’s apple-centred world is a working pastoral, attentive to aching limbs and heavy barrows, but the real local characters in the fields around Eragny are the highly distinctive fruit trees.

By the time the English war artist Paul Nash arrived in northern France in 1917, the landscape was utterly different. He wrote to his wife from the trenches, describing the remains of a French village, in “heaps of bricks, toast- rackety roofs and halves of houses here and there among the bright trees and what remains of the orchards”. Nash’s striking pictures of the blasted orchards, crowns blown off, trunks outlined like glass shards, turned apple trees into blackened, contorted figures, reaching hopelessly for the sun.

This is the tree that should have gone on growing peacefully in the orchards of France, England and Germany, where its fruit would have been picked, eaten and drunk by the latest generation of young men, just as it had been by their fathers and grandfathers. The apple tree is the Tree of Life, but it is also the Tree of Knowledge, the source of the taste of good and evil, of the fruit humans cannot resist and will always seize, unmindful of the consequences. The ravaged orchard showed what could not be told by shell-shocked survivors. What new beginnings were possible in this hideous, barren waste?

And yet, there is a deep-down, perennial urge to recover paradise, to start afresh. Dylan Thomas was born in 1914, but when he looked back on his formative years, he remembered being “young and easy under the apple boughs” in an idyllic childhood, “happy as the heart was long”. No blame attaches to the apple tree, which glows in the eternal light of lost youth; but the poet, writing in 1945, knew all about the chains of time as he looked back wistfully on his early reign as Prince of the Apple Towns. Cider with Rosie, Laurie Lee’s memoir of a Cotswold childhood in the 1920s, takes its title from his first taste of that “golden fire, juice of those valleys and of that time”. It is a vivid personal record of boyhood and the intoxicating apples that grow in paradise. Those born into a post-war world still demonstrate the same old impulse towards Eden, to recovering youth and innocence, to beginning again, whatever the wreckage all around.

Apple trees mean beginnings, childhood and the Garden of Eden, but they also mean enlightenment, experience and the future. If the apple has often carried the blame for human mishap, this tree has an unparalleled capacity to go on growing and giving us fresh starts.

This is an abridged version of the ‘Apple’ chapter from ‘The Long, Long Life of Trees’ by Fiona Stafford (Yale University Press, £16.99), published today

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments