15 products you thought were healthier than they actually are

Here are some of the most egregiously unhealthy products we've been tricked into buying

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Most people say that they want to eat healthier. It's a beautiful — and fairly new — thing.

The problem is that most of us don't know how.

But the next time you take a stroll down your grocery's “health food” aisle, take note: Most of what you're looking at likely doesn't belong there.

Here are some of the most egregiously unhealthy products we've been tricked into buying:

Fruit smoothies

The problem: Just because they pack lots of fruit, bottled smoothies are not necessarily healthy. But most are also incredibly high in sugar and calories. A 15-ounce bottle of Mighty Mango-flavored Naked Juice has 290 calories, 68 grams of carbs, and a whopping 57 grams of sugar — a 16-ounce bottle of Coke has 44 grams of sugar.

Marketing origins: Bottled juice and smoothie companies that capitalize on consumers' desire for fresh, healthy foods.

How it happened: The first blender was invented in the late 1930s, and Steve Kuhnau, who was reportedly experimenting with blending fruits and veggies to combat some of his own allergies and health problems, founded the first Smoothie King restaurant in Louisiana in 1973.

Cereal

The problem: Bowls of sugar-laden empty carbs got swapped for protein-rich components of the “balanced breakfast.” A cup of Reese's Puffs, for example, has 160 calories, 4 grams of fat (1 gram saturated), 13 grams of sugar, 29 grams of carbs and more than 3 grams of protein. A high-sugar, low-protein diet can increase hunger pangs and mood swings and leave you with low energy. Not exactly the best way to start the school day.

Marketing origins: Cereal companies.

How it happened: As Jaya Saxena writes for Serious Eats, “Cereal's position as America's default breakfast food is a remarkable feat, not of flavor or culture, but of marketing and packaging design.”

It all started, Saxena writes, with Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, manager of the Battle Creek Sanitarium, a Seventh-day Adventist health resort advertised as a place where upper-middle-class Americans could go for a health tune-up.

Kellogg, a vegetarian, advocated turning away from meat in favor of yogurt, nuts, and grains. Then, in 1895, C.W. Post, a former Battle Creek patient, founded his own cereal company with Postum, a “cereal beverage intended to replace coffee,” as its poster product.

Sports drinks

The problem: We've been wrongly convinced that we need sugar water to prepare and refuel after a hot date with the gym. In reality, exercise scientists recommend drinking water and eating or drinking 20 grams of protein, since studies suggest that it helps recondition and build muscles.

Marketing origins: Soda companies make the majority of sports drinks that you see on grocery-store shelves.

How it happened: Gatorade's “Is it in you?” black-and-white ads in the 1990s featured star athletes like Mia Hamm and Michael Jordan, who are shown literally sweating out the color of the Gatorade they were drinking. More recently, the company has come out with a lineup of “G-series” pre- and post-workout drinks that are supposedly designed to help you either prepare for or cool down from a workout.

Orange juice

The problem: Orange juice has become a required aspect of the American breakfast. In reality, juicing fruits removes all of their fiber, the key ingredient that keeps you feeling full and satisfied until your next meal. The result: mostly just sugar and water. And a high-sugar, low-protein diet can increase hunger pangs and mood swings and leave you with low energy.

Marketing origins: Sunkist, Tropicana, and the California Fruit Growers Exchange.

How it happened: Historian Harvey Levenstein writes in his book, “Fear of Food: A History of Why We Worry about What We Eat,” that biochemist Elmer McCollum, who helped discover vitamins A, B, and D and warned against vitamin-deficient diets in the 1920s, provided ample material for orange growers, whose sales at the time were sagging.

Under the Sunkist brand, the California Fruit Growers Exchange created a campaign focused on drinking orange juice to get these vitamins in an easy, tasty way.

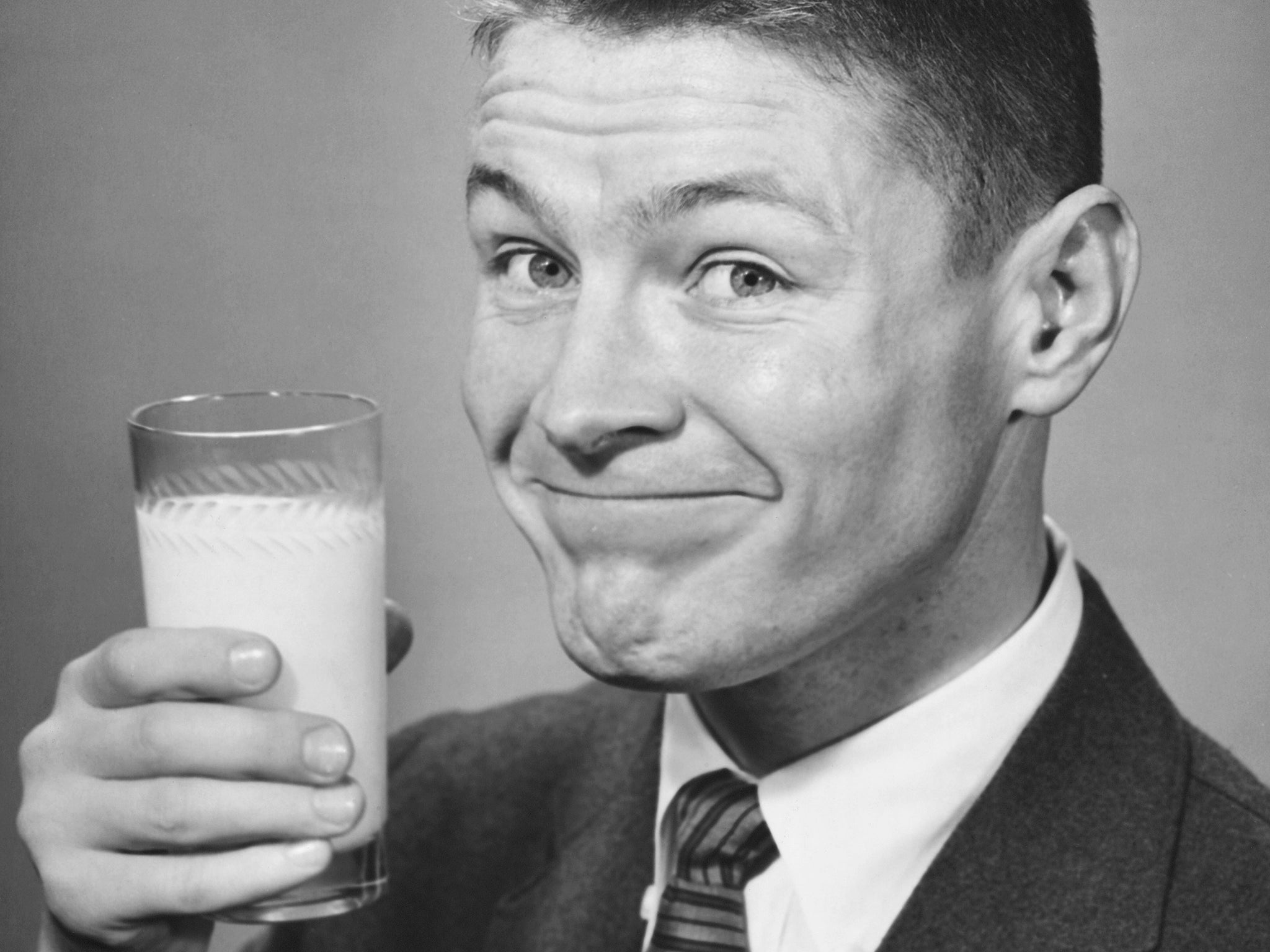

Milk

The problem: We were led to believe that we needed to drink milk to get calcium for strong bones, especially at a young age. In reality, there are a ton of veggies that are rich in calcium, including kale, collard greens, spinach, and peppers, just to name a few.

Marketing origins: The California dairy industry.

How it happened: In 1993, California hired advertising consultant Jeff Manning to boost lagging dairy sales. He brought on ad agency Goodby, Silverstein & Partners, which used its $23 million budget to create the “Got Milk?” campaign, which began with the idea that people want only milk when they run out.

Later versions of the ads emphasized its importance for health, like the above ad featuring actor Frankie Muniz with the text “Want strong kids?”

Bottled water

The problem: We've been deceived into thinking that bottled water is cleaner and healthier than tap water. Globally, we spend more than $100 billion on the bottled, yet otherwise widely available, good every year.

Marketing origins: Soda companies: Pepsi makes Aquafina, Nestle makes Dasani, and Coca-Cola makes Smart Water.

How it happened: Author Elizabeth Royte writes in her book, “Bottlemania: How Water Went on Sale and Why We Bought it,” that 92% of the nation's 53,000 local water systems meet or exceed federal safety standards and are at least as clean and often cleaner than bottled water.

So why has bottled water become so prevalent that sales surpass beer and milk in the US? Royte calls the phenomenon one of the “greatest marketing coups of the 21st century.”

Mouthwash

The problem: People have been led to believe that gargling with mouthwash is a better alternative to flossing. The US spent $1.4 billion on mouthwash in 2014.

Marketing origins: Listerine.

How it happened: For years, mouthwash company Listerine claimed that its products worked just as well as flossing. Those claims were false, as revealed in a 2004 lawsuit against the company for false advertising.

On 15 of its 24 products, Listerine said that it was “as effective as floss when used regularly.” The claim was based on two studies by the American Dental Association, which was funded by the maker of mouthwash, Pfizer. In 2005, New York judge Denny Chin ordered a stop to the ads, noting substantial evidence that no amount of mouthwash could replace daily flossing.

ConsumerAffairs.com reports that the class-action suit was thrown out in March 2010, but only because the claim was “over-broad” and that the majority of the population never encountered the advertisements because of a short shelf life.

Coconut water

The problem: We've been led to believe that this $4-a-serving beverage is a panacea for everything from post-workout dehydration to cancer.

Marketing origins: Zico, VitaCoco, and O.N.E.

How it happened: Since taking off globally in the mid-2000s, the coconut-water business has mushroomed into a $400 million industry dominated by just three giant companies. Ads featuring glowing celebrities like Rihanna relaxing on beaches helped push the trend into high gear.

Low-fat everything

The problem: We've been led to believe that low-fat products will lead to increased overall health and weight loss. An eight-year trial involving almost 50,000 women suggested that that's highly unlikely. When roughly half of them went on a low-fat diet, they didn't lower their risk of breast cancer, colorectal cancer, or heart disease. Plus, they didn't lose much weight, if any.

Marketing origins: The sugar industry. Sweet-snack and candy makers quickly realized that they could slap the “low-fat” or “fat-free” label on everything from yogurt to Twizzlers and see a boost in sales.

How it happened: Headlines of the 1980s and '90s were filled with missives that fat was killing us. Ironically enough, many food makers began replacing all this fat with another ingredient: sugar.

New recommendations show that healthy fats, like those from nuts, fish, and avocados, are actually good for you in moderation. So add them back into your diet if you haven't already.

Peanut butter and jelly

The problem: The PB&J is a ubiquitous lunch item among American children — there's a song about it, folks — but it's actually a less-healthy alternative to sandwiches made with hummus or lean meats.

Peanut butter is high in fat; jelly is high in sugar. Slap those ingredients between two slices of white bread and you've got a sandwich that packs 20 grams of sugar, 14 grams fat (3.5 grams saturated), and 400 calories.

Marketing origins: World War I rations officers, Welch's — which came out with Grapelade — and peanut companies that latched onto it.

How it happened: The Great Depression popularized peanut butter on bread as a cheaper-than-meat substitute for protein. When it was combined with Welch's Grapelade — one of the first iterations of jelly — in the rations of WWI soldiers in the US, the PB&J became an official hit.

Beef

The problem: We've been told that beef, which is high in fat and has been implicated in contributing to the California drought because of its large impact on land and water resources, is a go-to source of protein.

Marketing origins: The National Beef Board.

How it happened: The Beef Checkoff Program, a research- and advertising-funding pool created by the National Beef Board to stimulate sales in the US, came up with the “Beef: It's What's for Dinner” campaign in 1992. The campaign featured TV, radio, and magazine ads with actor Robert Mitchum as the narrator, as well as catchy Western music from the “Rodeo” suite by Aaron Copland.

The initial campaign ran for a year and a half and cost $42 million. Today, the program still owns and operates BeefItsWhatsForDinner.com, which features recipes and guides to picking out a cut of meat.

Gluten-free products

The problem: A lot of people think that gluten — a protein composite found in wheat, barley, and other grains that gives breads their chewiness — is bad for them, and that anything with a “gluten-free” label is, well, not.

In reality, unless you're one of the 1% of Americans who suffer from celiac disease, eating gluten probably won't have any negative effects on you.

Marketing origins: Consumers, gluten-free food makers, and food makers who responded to the trend by slapping “gluten-free” labels on foods that didn't have gluten to begin with.

How it happened: While the origins of the gluten-free craze remain disputed — it's still in its early days — it's been largely consumer-driven, Saint Joseph’s University marketing professor John Lang wrote in The New York Times.

“Whether consumers' reasons for demanding more gluten-free products are medically or nutritionally justified doesn't really matter; simply put, more consumers want more of these products,” said Lang.

By 2020, the gluten-free market is projected to be valued at close to $24 billion.

Granola

The problem: We associate anything crunchy and sold in bags in the health-food aisle with nature-loving hikers — people who get lots of exercise and keep their bodies lean and healthy. But granola is no health product. In fact, it's packed with sugar and calories — a cup contains about 600 calories, or the same amount as two turkey and cheese sandwiches or about four cereal bars.

Marketing origins: The first “corporate granola,” according to a 1978 Rolling Stone article, was Heartland Natural Cereal. Its roots reach back to the '60s, when Seventh-day Adventist Wayne Schlotthauer, who'd been operating the world's largest granola factory in California using a recipe his grandma had brought over from Germany, was approached by Layton Gentry. Schlotthauer sold him the West Coast rights to the granola recipe for $18,000.

How it happened: Luckily for Schlotthauer and Gentry — who was named “Johnny Granola-Seed” by Time — the '60s saw a resurgence in health-conscious eating habits and a desire to return to an “all natural” lifestyle. It was the perfect environment for granola to blossom.

Multivitamins

The problem: Close to half of American adults take vitamins every day. Yet decades' worth of research hasn't found any justification for our pill-popping habit. That isn't to say we don't need small amounts of vitamins to survive — without vitamins like A, C, and E, for example, we have a hard time turning food into energy and can develop conditions like rickets or scurvy.

Here's the thing: Research shows that we get more than enough of these substances from what we eat, so no need for a pill!

Marketing origins: Fruit-juice and vitamin manufacturers.

How it happened: Biochemist Elmer McCollum warned against vitamin-deficient diets in the 1920s, and juice companies as well as vitamin manufacturers hopped on the bandwagon to peddle their products.

Egg substitutes

The problem: For decades, we've been led to believe that eggs are bad for us because they're packed with cholesterol. Flavorless egg substitutes ranging from Egg Beaters to pre-blended cartons of egg whites packed grocery store shelves in the 1990s and early 2000s.

As it turns out, the cholesterol in eggs doesn't significantly raise blood cholesterol for the vast majority of us.

Marketing origins: US Dietary Guidelines, which for decades urged Americans to avoid eggs and strictly limit their intake of cholesterol from food.

How it happened: One odd thing that may have informed the original US Dietary Guidelines is the strange practice of studying cholesterol in rabbits, which are — surprise! — not humans. They're herbivores that don't eat animals or animal products. Regardless, at least one prominent researcher still extrapolated their rabbit results to people, Tech Insider reports.

This article has been updated since its original publication.

Read more:

• ALBERT EDWARDS: China is running out of money

• The Bank of England is quietly sounding the alarm over inflation

• Credit Suisse shares fell off a cliff to a 24-year low after the bank posted billions in losses

Read the original article on Business Insider UK. © 2015. Follow Business Insider UK on Twitter.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments