How it all got started: Prohibition America and the modern craft cocktail

After alcohol was banned in the 1920s, Americans got creative with their drink choices and the modern-day cocktail was born, says Jeffrey Miller

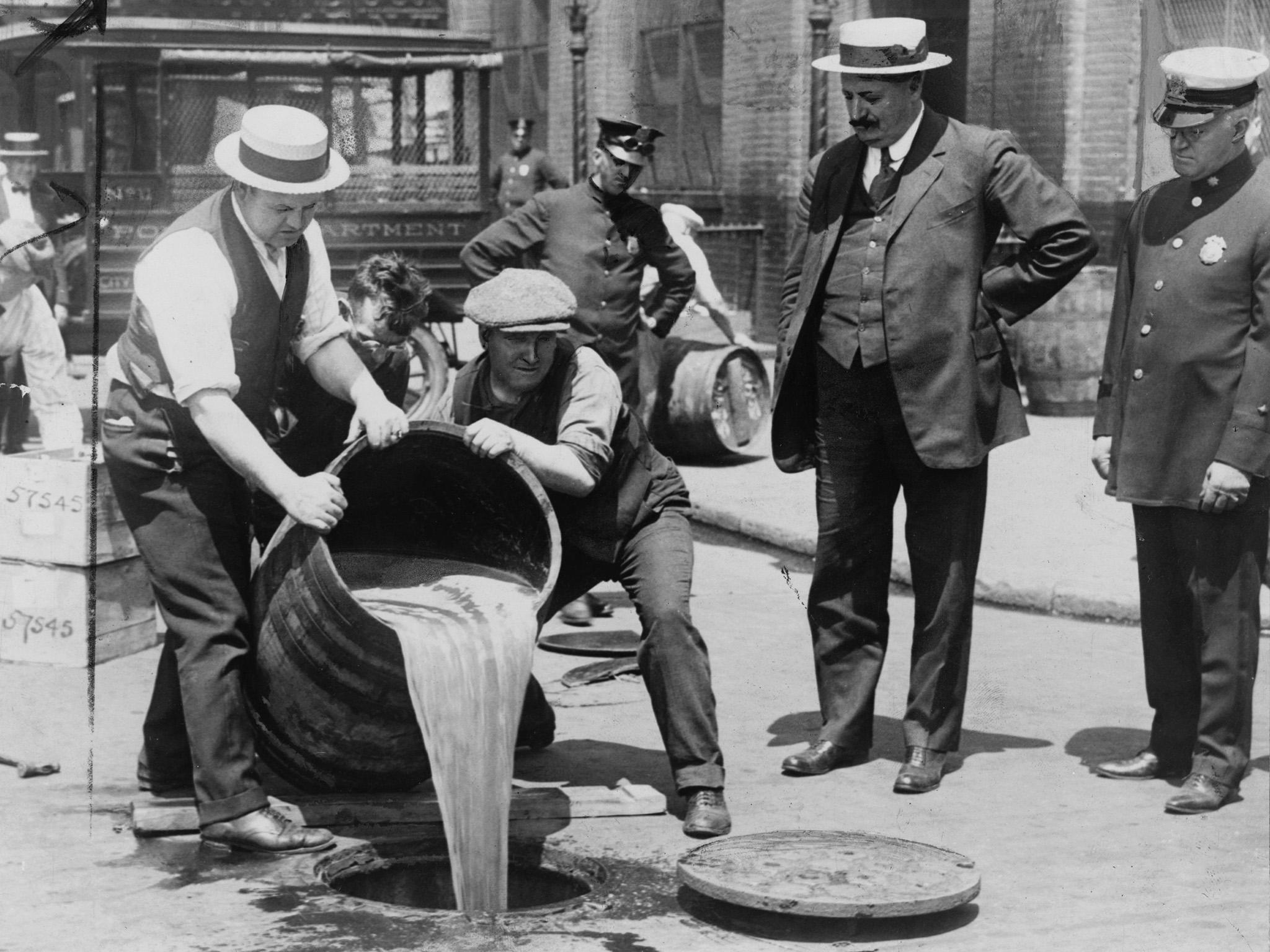

With America in the middle of a flourishing craft beer and craft spirits movement, it’s easy to forget that prohibition was once the law of the land.

One hundred years ago, on 16 Jan 1919, Nebraska became the 36th of the country’s 48 states to ratify the 18th amendment, reaching the required three-quarters threshold.

The law forbade the production of beverages that contained more than half of 1 per cent alcohol. Breweries, wineries and distilleries across America were shuttered. Most never reopened.

Prohibition may be long dead, but the speakeasies and cocktails it spawned are still with us. Much of the era’s bootleg liquor was stomach-turning. The need to make this bad alcohol drinkable – and to provide buyers a discreet place to consume it – created a phenomenon that lives on in today’s craft cocktail movement and faux speakeasies.

For better or worse, prohibition changed the way Americans drank, and its cultural impact has never really gone away.

Bootleggers get creative

During prohibition, the primary source of drinking alcohol was industrial alcohol – the kind used for making ink, perfumes and campstove fuel. About three gallons of faux gin or whiskey could be made from one gallon of industrial alcohol.

The authors of the Volstead Act, the law enacted to carry out the 18th amendment, had anticipated this: it required that industrial alcohol be denatured, which meant it was adulterated with chemicals that made it unfit to drink.

Bootleggers quickly adapted and figured out ways to remove or neutralise these adulterants. The process changed the flavour of the finished product – and not for the better. Poor quality notwithstanding, around one-third of the 150 million gallons of industrial alcohol produced in 1925 was thought to have been diverted to the illegal alcohol trade.

The next most common source of alcohol during prohibition was alcohol cooked up in illegal stills, producing what came to be called moonshine. By the end of prohibition, the Prohibition Bureau was seizing nearly a quarter-million illegal stills each year.

The homemade alcohol of this era was harsh. It was almost never barrel-aged and most moonshiners would try to mimic flavours by mixing in some suspect ingredients. They found they could simulate bourbon by adding dead rats or rotten meat to the moonshine and letting it sit for a few days. They made gin by adding juniper oil to raw alcohol, while they mixed in creosote, an antiseptic made from wood tar, to recreate scotch’s smokey flavour.

With few alternatives, these dubious versions of familiar spirits were nonetheless in high demand.

Bootleggers much preferred to trade in spirits than in beer or wine because bottles of bootleg gin or whiskey could fetch a far higher price.

Prior to prohibition, distilled spirits accounted for less than 40 per cent of the alcohol consumed in America. By the end of the “noble experiment” distilled spirits made up more than 75 per cent of alcohol sales.

Masking the foul flavours

To make the hard liquor palatable, drinkers and bartenders mixed in various ingredients that were flavoured and often sweet.

Gin was one of the most popular beverages of the era because it was usually the simplest, cheapest and fastest beverage to produce: take some alcohol, thin it with water, add glycerin and juniper oil, and voila – gin!

For this reason, many of the cocktails created during prohibition used gin. Popular creations of the era included the bee’s knees, a gin-based drink that used honey to fend off funky flavours, and the last word, which mixed gin with Chartreuse and maraschino cherry liqueur and is said to have been created at the Detroit Athletic Club in 1922.

Rum was another popular prohibition tipple, with huge amounts smuggled into the country from Caribbean nations via small boats captained by “rum-runners”. The Mary Pickford was a cocktail invented in the 1920s that used rum and red grapefruit juice.

The cocktail trend became an important part of home entertaining as well. With beer and wine less available, people hosted dinner parties featuring creative cocktails. Some even dispensed with the dinner part altogether, hosting newly fashionable cocktail parties.

Cocktails became synonymous with America the way wine was synonymous with France and Italy.

A modern movement is born

Beginning in the late 1980s, enterprising bartenders and restaurateurs sought to recreate the atmosphere of the prohibition-era speakeasy, with creative cocktails served in dimly lit lounges.

The modern craft cocktail movement in America probably dates to the reopening of the legendary Rainbow Room at New York’s Rockefeller Centre in 1988. The new bartender Dale Degroff created a cocktail list filled with classics from the prohibition era, along with new recipes based on timeless ingredients and techniques.

Around the same time, across town at the Odeon bar, owner Toby Cecchini created Sex and the City favourite the Cosmopolitan – a vodka martini with cranberry juice, lime juice and triple sec.

A movement was born: bartenders became superstars and cocktail menus expanded with new drinks featuring exotic ingredients, like the lost in translation – a take on the Manhattan using Japanese whiskey, craft vermouth and mushroom-flavoured sugar syrup – or the dry dock, a gin fizz made with cardamom bitters, lavender-scented simple syrup and grapefruit.

In 1999, legendary bartender Sasha Petraske opened Milk & Honey as an alternative to noisy bars with poorly made cocktails. Petraske wanted a quiet bar with world-class drinks, where, according to the code for patrons, there would be “no hooting, hollering, shouting, or other loud behavior”, “gentlemen will not introduce themselves to ladies” and “gentlemen will remove their hats”.

Petraske insisted on the highest quality liquors and mixers. Even the ice was customised for each cocktail. Many of what are now cliches in cocktail bars – big, hard ice cubes, bartenders with Edwardian facial hair and neckties, rules for entry and service – originated at Milk & Honey.

A lot of the early bars that subscribed to the craft cocktail ethos emulated the speakeasies of the prohibition era. The idea was to make them seem special and exclusive, and some of the new “speakeasies” incorporated gimmicks like requiring customers to enter behind bookcases or through phone booths. They’re meant to be places where customers can come to appreciate the drink – not the band, not the food, not the pickup scene.

Luckily, today’s drinker doesn’t have to worry about rotgut liquor: the craft distilling industry provides tasty spirits that can be either enjoyed in cocktails or simply sipped neat.

Jeffrey Miller is an associate professor and programme coordinator of hospitality management at Colorado State University. This article originally appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks