The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Mayukh Sen wants his new book to make you squirm

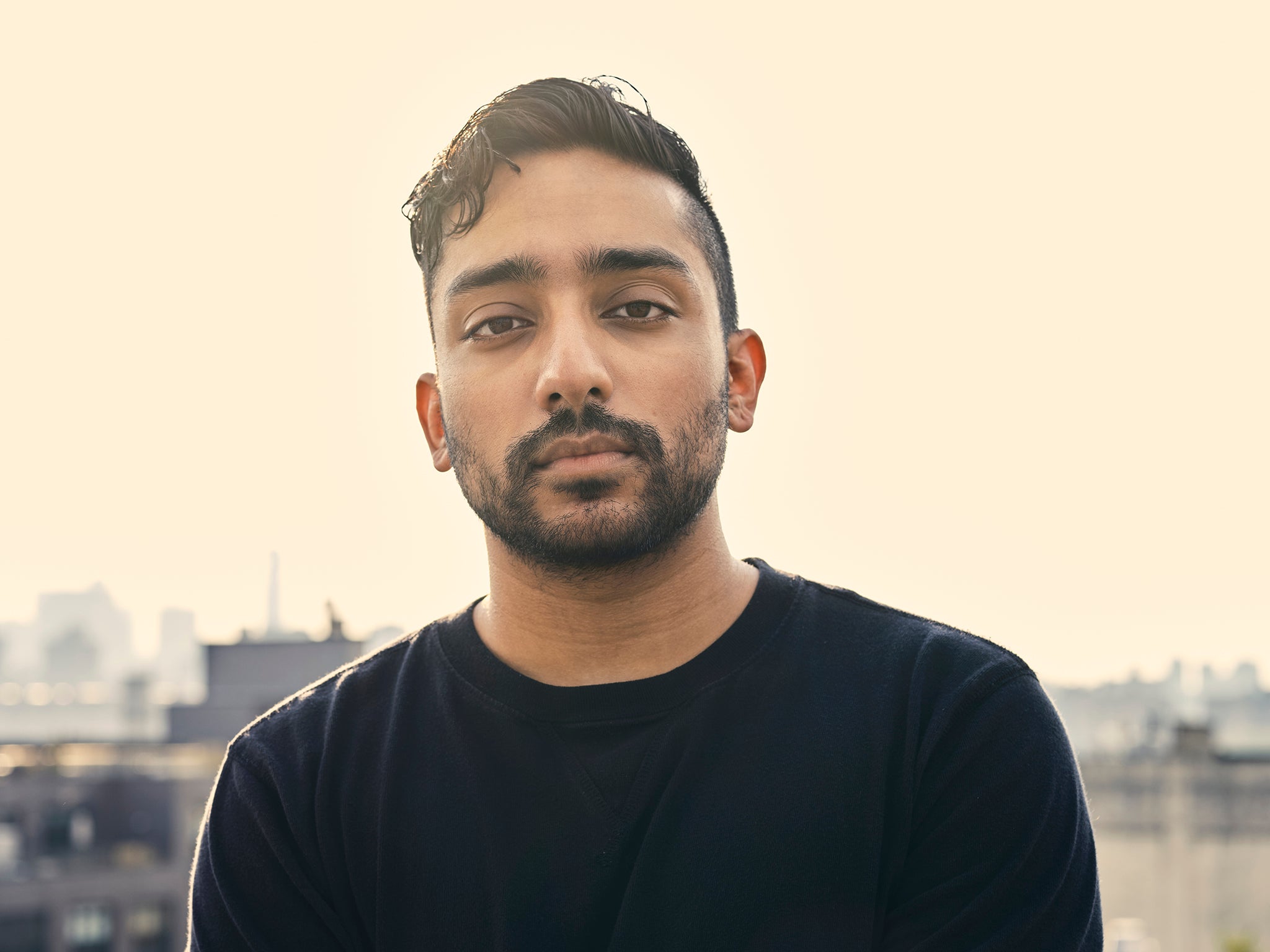

Susan Low speaks to the James Beard Award-winning food writer about his new book, how he accidentally fell into food writing and why he’s fed up with exclusionary food media

Who decides whose stories get told, whose cookbooks get written, whose dishes get cooked on television? Why do certain cooks and food writers become long-remembered household names while others struggle to have their voices heard and their culinary skills understood or appreciated? These questions and others are investigated in Mayukh Sen’s debut book Taste Makers: Seven Immigrant Women Who Revolutionised Food in America, recently published in the UK.

Sen, who recently turned 30, is not one to shy away from asking big questions. His willingness – compulsion, even – to do so has earned him a reputation as a writer of skill, as well as (by his own admission) something of an agitator. He’s only been writing about food for five years, but Sen has garnered numerous industry gongs, including, in 2019, one from the International Association for Culinary Professionals (IACP) for an article on “America’s most anonymous celebrity chef” published by TASTE.

In 2018, at just 26, Sen won a James Beard Journalism Award for a piece he wrote for Food52 (where he was staff writer at the time) about Pamela Strobel, aka Princess Pamela, a once-fêted African American chef, restaurateur and cookbook author who nonetheless died in obscurity. A line from this article hints at themes in his later work: “For decades, the chains of influence and power in the culinary sphere have remained static and white, and so have those sentries who dictate the worth of certain people’s contributions.”

Sen also teaches food journalism at New York University and food writing at Columbia University, so he’s a critical observer of the food media as well as a part of it. He describes himself as “a queer child of Bengali immigrants to America” and writes, “there will always be a sliver of me that feels as though I am on the margins – the margins of the food world, the margins of this country’s dominant social structures.” This insider-outsider perspective is what makes his voice distinctive – and the points Sen makes are equally relevant to the UK media.

It is possible – almost – to read Taste Makers as a kind of hagiography, a collection of portrayals of women who, despite the odds, accomplished great things, made valiant strides and blazed trails for others to follow. Yet this is no cosy armchair, feel-good read. “The book should make you squirm,” he writes. And it does.

Speaking to Sen via Zoom on publication day, I asked him how and why he became a food writer, his motivation for writing Taste Makers, what he hopes its publication might change – and, given his criticism of the industry – if he has hope for the future of the food media.

The accidental food writer

Sen didn’t set out to be a food writer. He graduated from Stanford University in California in 2014, where he studied film. “I grew up wanting to become a film critic,” he says. “I read critics like Pauline Kael and David Thomson voraciously as a teenager. After I graduated from college, I moved to New York, and I began freelance writing about topics like film, television and music – every aspect of culture except food. Because, to me, food writing had never seemed like a viable career path. I had always associated it with a certain kind of person, a certain demographic, to which I did not belong. I never really felt as though that industry could accommodate me.”

So, when he got a call from Food52 in 2016 asking if he would like to interview for the position of staff writer, he was somewhat bemused. “I took the meeting reluctantly and, as I was going through the interview process, I was asking myself ‘What am I getting myself into here?’ But once I was offered the job I thought, ‘This will be a fun change of pace. I’m early in my career and perhaps it will open up new opportunities’.”

Sen’s motivation certainly wasn’t recipe-writing (“I am still a pretty lousy home cook and I’m not the best person to go to for restaurant recommendations,” he admits). Instead, he says, “what drew me to this line of work was writing about the people who make food – especially because the very concept of food as a tool for creative expression was just so foreign to me. I had grown up seeing food as an object of consumption, something that was meant to sustain you from one day to the next – so I’m fascinated by people who have made this creative pursuit their profession and I wanted to delve into their stories.”

Sen essentially learned on the job at Food52. “I was so new to writing about food that I began acclimating to this new topic by writing personal essays. But after a few months, I felt as though I had exhausted every food story I had. I became incredibly bored with myself as the subject,” he laughs. “I got the personal essays out of my system, but I still felt very isolated in food media in general.”

Writing helped him to work through that sense of alienation. “I began to gravitate toward the stories of people from marginalised communities. Through telling their stories I came to feel a bit less alone in the industry. And I saw writing these stories as my own form of culinary education.”

The seed of the idea for Taste Makers was planted in 2017 when a friend suggested bringing together the portraits he’d written to tell a larger story about immigration and food. The idea took root a year later, in response to narratives in the food media that Sen felt needed to be addressed. “Within the American food media, the proliferation of certain talking points unsettled me a bit,” he says. “They were often along the lines of ‘immigrants get the job done,’ and ‘immigrants feed America.’

“I do think that those talking points were well intentioned, but they were often coming from white-led publications and white editors who were maybe inadvertently abstracting the lives and creative desires of immigrants themselves. I found that positioning so troubling. I felt that the best way for me, within my very limited skill set as a storyteller, to combat that train of thought was to tell the stories of individual immigrants who had shaped America, in the most granular and intimate way possible. That is how this book was formed.”

Seven telling tales

The seven women whose stories he investigates are Chao Yang Buwei from China; Elena Zelayeta from Mexico; French-born Madeleine Kamman; Marcella Hazan from Italy; Indian-born Julie Sahni; Iranian exile Najmieh Batmanglij; and Norma Shirley from Jamaica. Some, such as Chao Yang Buwei and Najmieh Batmanglij, wrote definitive cookbooks about their cuisine; some, such as Julie Sahni, Madeleine Kamman and Norma Shirley, were chefs, restaurateurs and educators. “All of these women used their food to tell the world where they came from and what remained of it in America,” writes Sen. “They did so with no shame, only pride.”

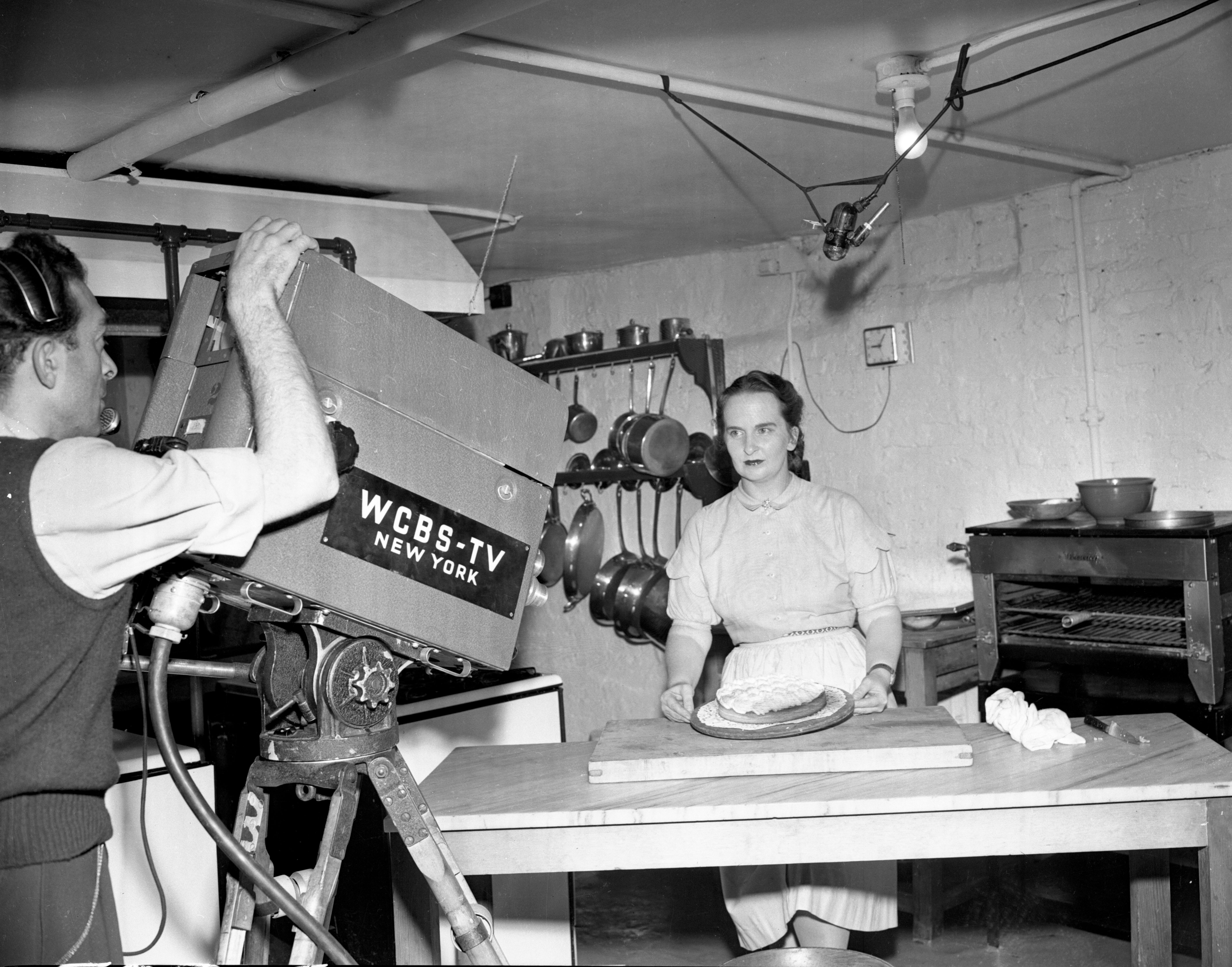

In addition to these seven, Sen writes briefly about Dione Lucas, “a pioneer for America’s understanding of French cooking”. Of British parentage, Dione was the first female graduate of Le Cordon Bleu and, from 1947 until the 1950s, she hosted her own cooking show in the US, originally called To the Queen’s Taste (later renamed The Dione Lucas Show) – long before Julia Child began hosting The French Chef in 1963. Yet Lucas’s name is not one that resonates. Why?

“When I was researching this book, I came across a number of references to her that described her as ‘too chilly’ and ‘too remote’, which I took to be saying that she was ‘too foreign’ for American audiences to really accept. They stereotyped her as sort of having this stiff-upper-lip British persona that was anathema to American audiences in the years immediately following World War Two.” Sen also came across “murmurs of alleged issues regarding substance abuse in her life”.

He says: “That really disturbed me because I feel as though the culture at large has often been uncharitable to people who have sometimes struggled. I say this as someone who has been sober for two years now; I understand how hostile the surrounding world can be to people who are fighting battles in private. And that just reinforces my desire to tell her story in a way that is sensitive and that puts her accomplishments first – because they are too significant to be ignored.”

One of the most discomfiting stories in Taste Makers is that of Norma Shirley, who was born in 1938 in Jamaica. After graduating from boarding school in Kingston, Norma, an ambitious student, travelled to Scotland to study surgical nursing at Southern General Hospital (now the Southern General University Hospital) in Glasgow and worked as a helicopter rescue nurse. Her first attempts at cooking were based on ingredients that were utterly unlike the rich island cuisine she was used to.

After returning to Jamaica in the early 1960s, Norma married Michael Shirley, a doctor who had been raised and educated in England. On honeymoon in France, Norma fell in love with the complex subtleties of French cuisine. She taught herself to cook French food from a pile of Julia Child’s cookbooks, slowly honing her technique and working with Jamaican ingredients and seasoning.

Michael Shirley’s job took him to London, where the couple and their young son lived in Dulwich, and eventually to New York, where she worked as a chef and food stylist in the 1970s. She ran a fashionable restaurant in Massachusetts in the 1980s, serving “New England food with Jamaican flair”. She eventually returned to Jamaica and opened restaurants that, Sen says, “led to a food revolution in the country”.

When he was researching Shirley, Sen found an aspect of her story particularly perturbing. He says: “When I was writing the chapter on Norma, I came across a line from a 1999 Esquire review of her son’s restaurant in Florida, in which the reviewer posited that ‘Jamaica does not leap to mind when I think of great food’. Such a casual swipe at an entire country’s cuisine! To see that, as recently as 1999, that would pass muster in the food media – it was really upsetting. I think that now, at least in my experience in the food media, people in power are a bit more crafty about the ways in which they try to disguise their discriminatory attitudes.”

An independent future?

Given Sen’s criticisms of the food media, does he have hope for the future? “Yes, I do, cautiously have hope. But most of that hope is reserved for independent food media and independent food creators.” Sen cites Whetstone, a Black-owned independent food publication and media company in the US and, in the UK, Jonathan Nunn of the newsletter Vittles, which he describes as “one example of someone who has been able to build a publication that is detached from the traditional institutions of power that have commanded food media for so long”.

Our interview concludes with Sen saying: “It is my hope that independent food media will flourish to such a degree in the years to come that they render the more traditional institutions obsolete. I want power to shift away from those publications that have determined for so long who gets money and how much money they get.”

“And,” he says, “I want my students to aspire to write for places like Vittles and Whetstone and see that as a sign that they have ‘made it’ rather than writing for magazines and newspapers that have been around for decades, yet have more often than not shown that they do not really care to render the stories of people from marginalised communities with sensitivity.”

You can read Taste Makers as a collection of food-centric biographies. You can read it as a measure of how the food world has changed (or not) in the seven decades covered in the book’s pages. You can read Taste Makers as a critique of how the food media works. It could also be read as an invitation to think about whose stories will be told, and how, in decades to come. Because, more than ever, it is we, as readers and food lovers, who are the sentries, we who have the power to bring new stories and fresh voices into the light.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks