Gastrophysics: The new science behind your eating habits

The food industry is enticing people to buy more with clever tricks. From the placement of spoons in adverts to picking the right genre of music, there’s many ways to manipulate the taste buds

In 2014 and 2015, food was the second most searched-for category on the internet. Pornography was number one. That’s according to Professor Charles Spence in his new book Gastrophysics: The New Science of Eating.

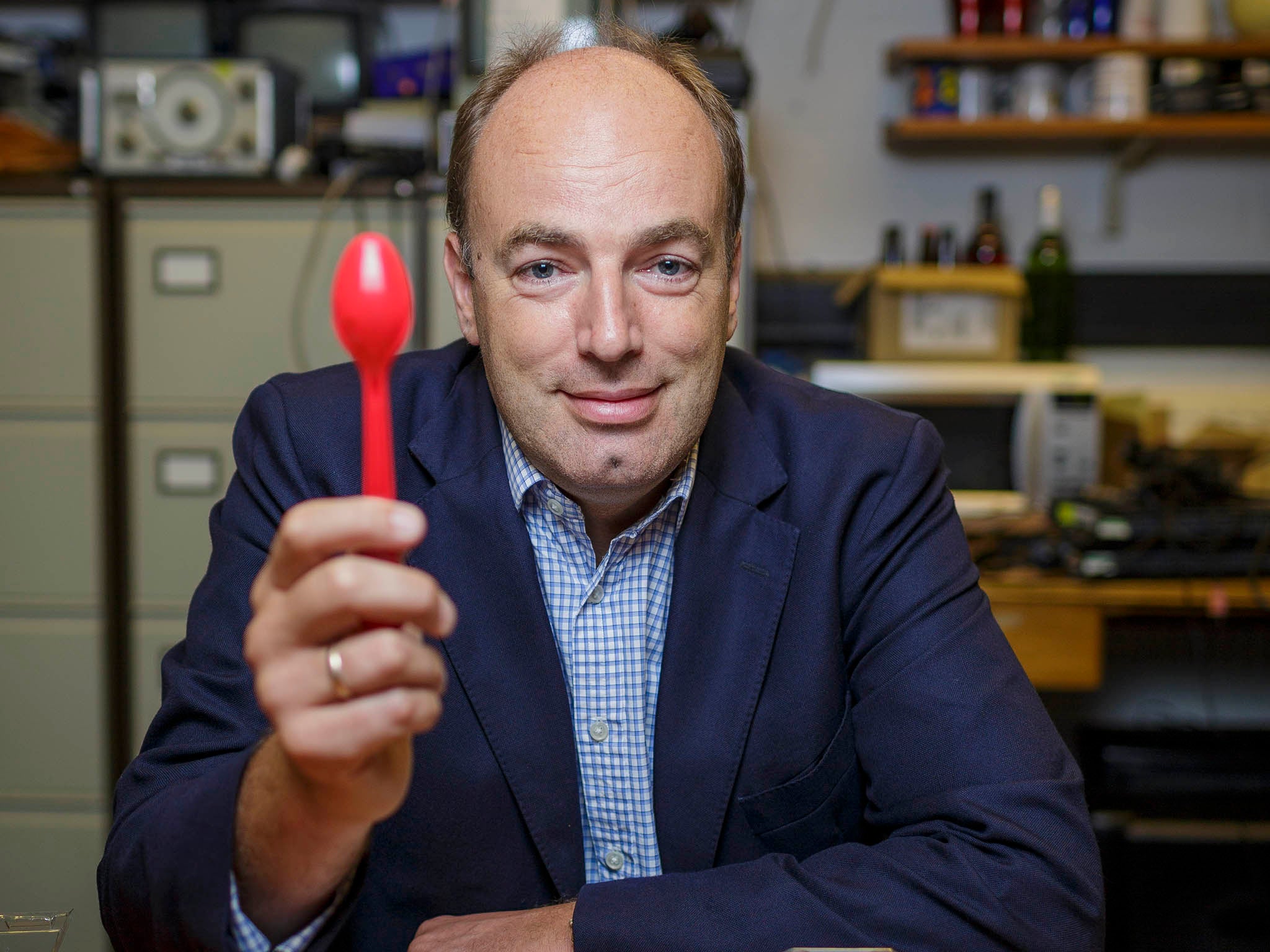

Spence is an experimental psychologist who started the Crossmodal Research Laboratory at the University of Oxford in 1997. Today, his work is largely funded by the food and drinks industry. He looks at not what people say they think about food but at what they do and why they do it. To understand this, Spence says, you have to dig deep; you have to dig into the mind.

Often, it’s about expectations – what we think we’re going to eat that matters. And by the time the fork hits your mouth, your mind has already decided if that’s going to be thumbs up or thumbs down. Sceptical?

Which would you order from a menu – Patagonian toothfish or Chilean sea bass? It turns out that it’s the same thing and when toothfish got a new name, sales jumped more than 1,000 per cent. It’s a meeting of mouth and mind and contrary to what we think, mind has the upper hand.

Tasting something bitter can make you feel more hostile while something sweet more romantic. Even thinking about love can make you think that water tastes sweeter. What we think food will taste like is just as likely to be influenced by what colour it is and how it smells, making our sense of taste seem like an unreliable witness at best. Without a sense of smell, Spence says, it’s tough to tell if what you’re tasting is an onion or an apple, red wine or cold coffee.

Spence poses intriguing questions like, can you taste the shape of food? Turns out that food served in rounder shapes was perceived to be sweeter than something angular. White plates “make” food taste sweeter and more flavourful than black, and orange plastic makes hot chocolate taste more “chocolatey” than white.

But does it matter? Consider this: a US based study found that vulnerable patients suffering from Alzheimer’s disease ate 25 per cent more food and 84 per cent more liquids when their plates and cups were switched to high contrast colours. Not surprisingly, retailers and food marketers are cashing in on this. Imagine a bowl of soup on a package. If there is a spoon in the photograph and it’s coming in from the right, you’re 15 per cent more likely to buy it than if the spoon is coming from the left. Reason? Probably something as simple as that most of us are right handed, so we identify with the right without even realising it.

Restaurants are in on the game too. Spence points to studies that show that we’ll pay twice as much for the exact same food when it looks more visually appealing. Serve a dish with heavy cutlery and we’ll pay more than we would for the same food, on the same day, in the same restaurant with lighter cutlery. Play classical music and we’ll spend more, faster music and we eat and run, but slower music and we spend 10 minutes longer eating.

If you’re coming to the conclusion that you’re not in control at all, you’re probably not far off. Think about this: researchers in Britain changed the music played in the wine section of the supermarket. When they played French music, the majority of shoppers bought French wine. Switch to German music and – you guessed it – we started filling our baskets with riesling.

Turns out that our minds play tricks on our taste buds. We can’t trust what we see, let alone what we taste and our memories are at best highly suspect. Spence takes a jovial pleasure in puncturing our perceptions and showing that there’s a lot more going on in our mouths than what we think we’re tasting.

He pushes us to consider where food might be in the not too distant future. 3D printed food? Vibrating forks? The stuff of sci-fi? After reading Gastrophysics I’m not so sure.

Spence tells the story of his grandfather who ran a grocery in the north of England. He used to sprinkle coffee beans behind the counter of his grocer’s shop. Cue a customer walking in and he’d crush the beans under his foot, releasing an intoxicating aroma of coffee. What he knew intuitively – and his grandson has proven scientifically – is that we’re all influenced in what we eat and drink without even knowing it. With Gastrophysics, Spence has given us much food for thought.

‘Gastrophysics: The New Science of Eating’ by Charles Spence (Viking, £14.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks