How Filipino food is finally finding its feet in the west

Now out of the shadows, Pinoy cuisine is enjoying its time in the sun, says Nicole Ponseca and Miguel Trinidad, who own a Filipino restaurant in New York and relish seeing non-Filipinos come into eat there

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When we first opened Jeepney and Maharlika, we primarily served Filipinos and Filipino Americans. And I could feel what my guests felt: pride.

It was no small thing to be in a restaurant that was unabashedly Filipino. It was our party, and everyone was invited.

Now when I look around the restaurants, I get a little gobsmacked seeing people from all walks of life coming to try Filipino food. When I was growing up, seeing a non-Filipino in a Filipino restaurant meant the person was likely married into the family. Now all kinds of people come just for the food.

I also love that the restaurants have become places to have a first date or celebrate a special occasion; you can bring your coworkers or your mom and dad.

But it always comes down to the food. And it’s a joy to have people from all over the world dine on our style of cooking the flavours of the Philippines.

Running a restaurant is filled with pressure. Miguel and I receive a lot of feedback and we appreciate it – even when the reviews are mixed. Some guests don’t like the way we serve our dishes or are surprised that a non-Filipino is cooking Filipino food. Others say that their mom’s adobo is better than Miguel’s. And how could it not be? Who else can cook like your mother?!

But in the years that our restaurants have been open, the conversation has changed. Before, the barometer of success for an ethnic restaurant was how much the food resembled your mother’s cooking. Now it has broadened.

For me, I want to know how much a restaurant can push the envelope and remain devoted to flavour. So it’s with great pride that I see Filipino food happening all over the world. Kamayan, kare kare, and kinilaw are on menus cooked by Filipino and non-Filipino chefs alike. We see the Filipino food movement in New York City, but in other cities, too – New Orleans, London, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Washington DC, all have groundbreaking modern Filipino restaurants.

Out of the shadows, Filipino food is finally enjoying its time in the sun. And diners and chefs are going deeper – researching their roots, making things from scratch, redefining what we previously accepted as culinary truths. There is a desire to know who we are, in the context of the global interest in our cooking: regional specialties, the ingredients themselves, the history and culture behind our food, the country itself – especially because Filipino cuisine is as rich and diverse as the more than 175 languages and dialects spoken in the Philippines. It finally feels like a Filipino food renaissance.

People have said Filipino food is a cuisine of occupation, because so many waves of people from elsewhere inserted their culture into ours, often by force. We were a Spanish colony for three hundred years, and one under dear ol’ Uncle Sam for almost forty more, and even Japan invaded during World War II. The Chinese came centuries ago as traders and businessmen, and Indians, Arabs, South Asians, and other nomadic Pacific Islanders came even earlier.

The Philippines also has many families with Mexican roots, as the Spanish fleets brought settlers from Mexico, another Spanish colony. These factors are important to keep in mind when you think about the Filipino culinary family tree, and personally, I love knowing how Filipinos have influenced the world and how the world has influenced us. (In fact, Filipinos were among the first Asian people to settle in the New World.)

But there is much more to Filipino food than colonialism, exploration, and occupation, and the food starts not with these cultures but with our Malayan ancestors and all that was on the islands from the beginning. This includes ingredients, ways of cooking, cultures, and tribes that did and still do change from province to province, island to island. To paraphrase José Rizal, a 19th-century Filipino national hero who helped the Philippines finally break from Spanish rule, “You must know where you’re from in order to get where you’re going.”

Defining features of Filipino cuisine

Calling these Filipino flavours “sauces” is a bit of a stretch – technically they are more like flavour profiles. But I like to borrow the term mother sauce from the French because I believe that, like a béchamel or velouté, these five profiles are the building blocks of Filipino cuisine and the foundation of the recipes in this book. The flavours are built on the ingredients Filipinos traditionally had available as a tropical island country: Miles and miles of shoreline give us ample seafood; coconut and palm trees grow with abandon; we have copious fresh fruits that are used when sour and green or ripe and sweet; and lush fields of rice grow using terracing techniques developed in the Philippines before being sent out into the world.

Sour

Maasim is Tagalog for “sour.” There are some who like foods so spicy it leads to sweat, shakes, and gasps for air, but I’ve met countless Filipinos with a preference for a sourness so intense it provokes salivation and lip-smacking. Sourness is a cuisine-defining flavour profile. Sour is the gateway to Filipino food, and it sets the cuisine apart.

Filipinos cook with tart fruits like unripe guava and papaya, using tamarind pods and leaves, and squeezing tart calamansi citrus fruit into nearly everything – are there other cuisines that rely on such a variety of vinegars and souring agents? Vinegars are made from palm, pineapple, sugarcane, rice, coconut, and countless other fruits – which are plentiful all over the Philippines – and then those vinegars are infused with chilis and garlic and all manner of aromatics and herbs. In fact, adobo, the stew that is the best-known dish in the Philippines, can be broadly defined as anything cooked in vinegar. We make ceviches, or kinilaw, with a variety of proteins, and vegetables are “cooked” with vinegar; we also have many versions of sinigang, a Filipino sour soup made using almost every possible combination of sour fruits and citrus, from unripe watermelon to a precious little tree fruit called bilimbi (tree cucumber).

There is some kind of sour element in every Filipino meal, if not directly in a dish, then applied in the form of a marinade or the condiment called sawsawan, which, generally, is not meant to be a last-minute splash or dash, but to work deeply with the food and marry the flavours.

Funk

In many traditional dishes, the umami kick is not from meat but from the funk of fermentation. First, you have patis, which is the Filipino version of fish sauce, a salty, funky liquid made from fermenting seafood in salt. It is largely used instead of table salt; thus, nearly every dish has a little bit of funk.

And perhaps even more important is the thick seafood paste called bagoong. This ingredient – which has several variations – is a defining one in Filipino food. Add bagoong to a simple vegetable broth, and you have sustenance; add it to a coconut milk sauce, and you have instant complexity. Take the dish called pinakbet, the ratatouille of the Philippines. It’s a simple vegetable dish of eggplant, summer squash, squash blossoms, pumpkin, and Southeast Asian long beans simmered with tomatoes, ginger, onion, bay leaf, and bagoong, in which the bagoong provides the real flavour. And a dollop of the paste is what takes the sweet, rich sauce of kare kare from any ordinary oxtail stew into a dish that is uniquely Filipino.

It’s important to note that Filipino food does not get funky, complex flavours from seafood alone. There are several other traditional fermentation techniques used in the cooking. Suka – Filipino vinegar – is fermented from palm, coconut, or cane sugar. Many sausages or cured meats get a sour tang from natural fermentation techniques (just like the process for making salami). Salted eggs – used liberally in salads, sauces, and baked goods – get a bold tang from being cured in salt.

Tomato

Three hundred years of Spanish rule made its mark on Filipino food, and today there are nearly half a dozen iconic Filipino dishes rooted in a tomato-based sauce, often enhanced with garlic and onion. While they are obviously Spanish in origin, the addition of seasonings like patis gives them an unmistakable Filipino flavour. Like all Filipino foods, they vary slightly from region to region and kitchen to kitchen, but they include things like menudo, a rich, deeply flavored stew made with meat like beef or lamb shank, tomato, chicken livers, carrots, potato, and the obviously Spanish addition of olives. Kaldereta can be similar, though it’s often slightly sweet or tangy and includes sweet green peas, also not an ingredient originally grown in the Philippines. And there’s lengua estafada—tongue with tomato sauce—and chicken guisantes, or chicken stewed with fish sauce, tomatoes, and sweet bell peppers.

The Holy Trinity

In French cooking, the holy trinity is the mirepoix, a diced mix of onion, celery, and carrot that is sautéed in fat until it is soft and sweet and then used as the base for all kinds of soups, stews, and sauces. The Spanish have their sofrito of onions, garlic, and tomato, and the Cajuns use onions, celery, and bell peppers. There are likely many other holy trinities in the cuisines of other cultures. For Filipinos, our holy trinity is browned garlic, Spanish onion, and ginger (notes most prevalent in Visayan cooking). Alternatively, instead of or in addition to ginger, our trinity might include some kind of umami in the form of pork belly (the Philippine diet leans on pork, and we even have a native black pig, baboy damo), canned liver paste, or bagoong.

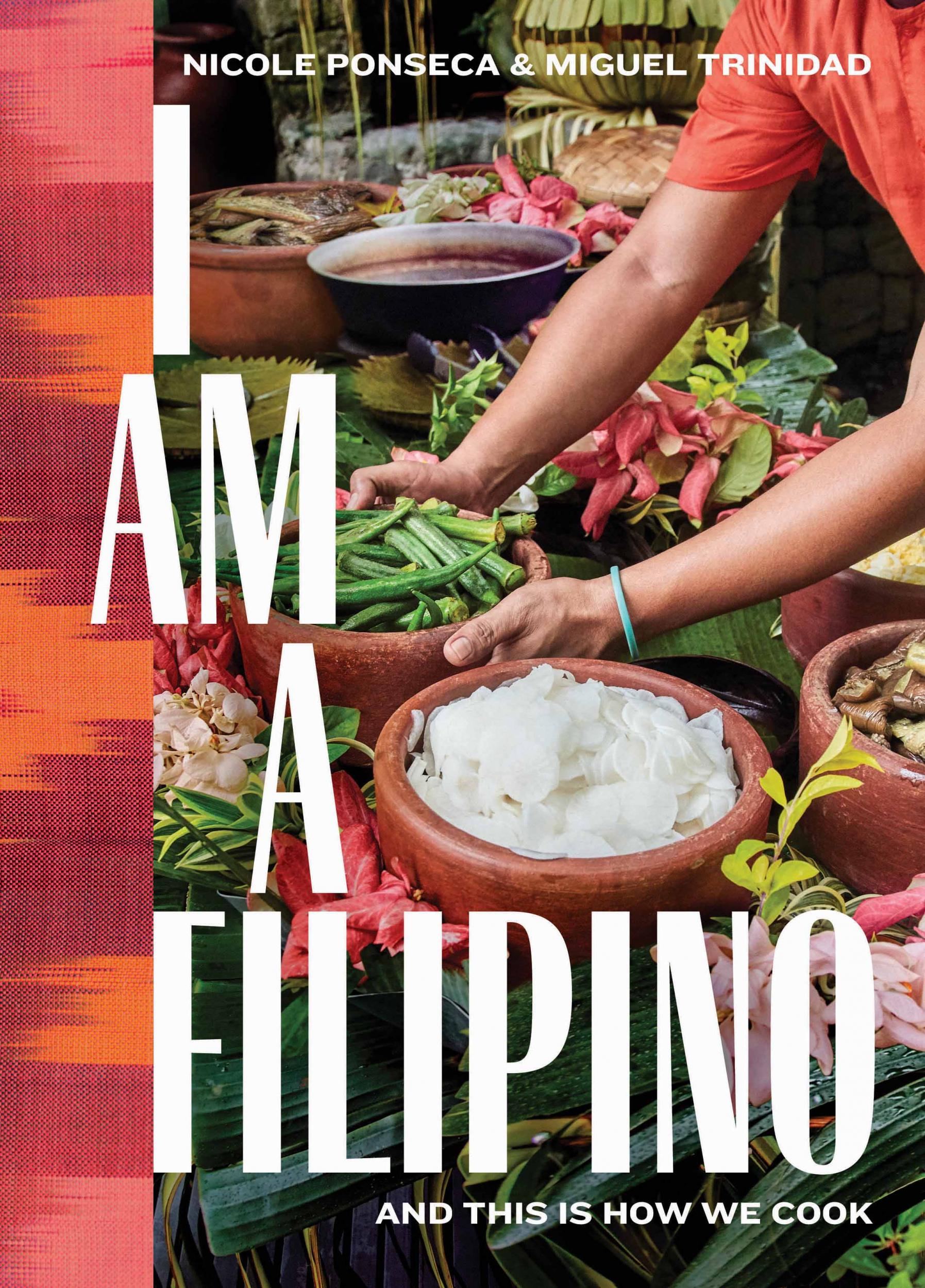

Extracted from 'I Am a Filipino' by Nicole Ponseca and Miguel Trinidad (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2018. Photographs by Justin Walker

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments