The food chain: How big business bought up the ethical market

You can play a game with the trendy food products on supermarket shelves. It's called "spot the owner". What you're looking for – when you scan the tin, tub or pack in your hand – is the actual owner of the company. Not the brand, you understand, but the business that ultimately collects the money you hand over at the till.

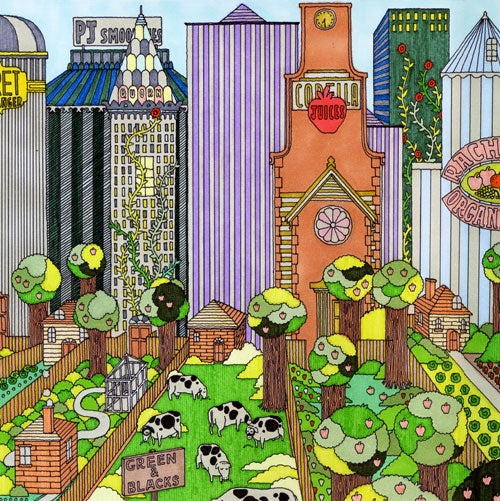

You can play it with big-name "ethical" products like Green & Black's organic chocolate, Rachel's Organics yoghurts, Seeds of Change pasta, sauces and cereal bars, or Ben & Jerry's ice-cream. But, no matter how long you look at the label, you won't have much luck finding the owner.

The companies' websites are scarcely better. But after the cheering story of how an individual/friends/couple decided they could improve people's health/the soil/the world, you can find the answer if you're prepared to try hard enough (though some advance information helps, too). What you will discover is that the owner is often a multinational company, whose core business is very different – often shockingly so – to the virtuous product in your shopping basket.

All of the brands mentioned above, for instance, are now owned by big business empires. Green & Black's, maker of gourmet high-cocoa bars, is owned by Cadbury, the makers of mass-market, low-cocoa bars. Ben & Jerry's groovy, often highly political, ice-creams belong to the Anglo-Dutch household-goods giant Unilever. Rachel's Organics, a big organic dairy brand, is owned by the US's largest dairy company, Dean Foods, which produces 2bn gallons of conventional milk a year.

The trend is not limited to a few big players, either. Almost all the medium or large overtly ethical companies whose products are sold in British supermarkets are owned by large international organisations. Big corporations have been buying consumer credibility since the mid-1990s, and have put their foot on the gas in the past two years, with the sharp rise in consumer spending on ethical products – and their profitability.

Back in 1997, Seeds of Change, the organic pasta, sauce and cereal-bar outfit, was sold to the confectionery giant Mars, which does not make great play of its ownership of the business.

In 1999, Copella apple juice, the traditional Suffolk apple-juice company, was bought by the orange-juice brand Tropicana, now part of the Pepsi empire.

In 2000, Unilever scooped up Ben & Jerry's, whose funky flavours include Cherry Garcia and Bohemian Raspberry, for £175m. A year later, a third of the Pret A Manger sandwich retailer, which shuns "obscure chemicals, additives and preservatives", was sold to McDonald's, which uses E-numbers 578 different ways. All of Pret went to the private-equity company Bridgepoint for £345m in February this year.

In 2003, Dean Foods bought out the remaining 87-per-cent stake in Horizon Organics, owner of Rachel's Organics. Then, in 2005, for an undisclosed sum, former City broker Harry Cragoe sold his health-giving P J Smoothies company to Pepsi. In the same year, the UK's biggest food manufacturer, Premier Foods, bought the fast-growing vegetarian brands Cauldron and Quorn, and the next year, Lion Capital, a private-equity company, took over Kettle Foods, the maker of premium hand-cooked crisps without monosodium glutamate.

In 2007, a stake in organic vegetable-box delivery company Abel & Cole was sold to another private equity firm, Phoenix, whose other interests include the oil and gas logistics company ASCO.

In February 2008, one of the remaining stand-alone organic pioneers, the baby-food company Organix, was bought by the Swiss food firm Hero, giving its campaigning founder Lizzie Vann what is assumed to be a substantial but undisclosed payout. In March 2008, the health-food group Dorset Cereals, which makes muesli, porridge and chocolate bars, was bought for £50m by the private-equity firm Lydian Capital.

Perhaps most pertinently of all, last month Tyrrells, the premium crisp-maker founded by a Herefordshire farmer, was bought by another private-equity company, Langholm Capital, for almost £40m. William Chase, the farmer, made headlines by insisting that his crisps would not be sold by Tesco. Its new owners say that now they may be.

So, the question is: why are these companies selling out? And does it matter? Are "ethical" companies owned by larger companies somehow less ethical – and are their ideas or business practices changed by the takeovers?

or the first time in our transatlantic phone call, Jerry Greenfield pauses and a seriousness falls on the conversation, which is taking place at 7.30am US time. "I don't quite know," he says softly. "I don't know what we could have done. I have never come up with a good answer to that."

Greenfield, a 57-year-old millionaire social entrepreneur, is wondering whether he could have done anything to halt the sale of the hippie ice-cream empire he and his schoolfriend, Ben Cohen, started in 1977 after he had failed to get into medical school for the second time and his friend had been fired from a series of low-paid jobs.

They took a correspondence course in ice-cream making, bought a dilapidated shop and starting selling scoops of their ice-cream out of the back of a VW camper-van. Their company had ideals. Ben & Jerry's wasn't a normal business; it bought local milk from well-treated cows and donated 7.5 per cent of its profits to good causes. The duo could probably have fought off the Unilever bid if they had not sold a majority stake in the company to Wall Street in 1985 to fund expansion. When Unilever offered a bumper $43.60 a share, the new directors accepted.

"We always considered the company fiercely independent and wanted it to remain that way – primarily because we think the mission of Ben & Jerry's is very different to mainstream corporate thinking," Greenfield says. "We didn't want to be acquired by anyone." The founders tried to mount an alternative buyout, but it failed.

Still, Ben and Jerry made £15m each from the sale of their 15-per-cent stake.

o find out why companies are bought out, you need only look around a British supermarket, each of which is a cathedral of consumerism. An out-of-town store is stocked from ceiling to floor with around 30,000 products. Some of them are unbranded, like carrots, or are the supermarket's own brand; and some are merely different sizes of the same line.

But that still leaves hundreds upon hundreds of brands competing for attention, all with different identities, designs, colours, advertisements, slogans, stories.

We all know about Oxo's distinctive red-and-white livery, or Bisto gravy's televisual nuclear family; we readily recognise Fray Bentos pies, or Robertson's Golden Shred, or Smash, the instant potato reputedly favoured by aliens. Campbell's soup and Gale's honey have a reassuring, homely feel yet to be emulated by newer, highly technological vegetarian foods like Quorn. Bread buyers can choose between a Mothers Pride plastic white, Nimble for slimmers, or wholesome Hovis, whose 1973 TV advert of a boy pushing a bike up a cobbled northern street was, in fact, filmed in Dorset. Look for something sweet and you can have Angel Delight, Hartley's jelly, Mr Kipling's cakes, or Ambrosia rice pudding.

What you may not know, however, is that all these brands, and many more – including Sharwoods, Crosse & Blackwell, Birds, Lyons, Sarsons, Marvel and Homepride – are owned by just one company: Premier Foods.

Food brands are divvied up between a handful of big players, who have economies of scale and negotiating power with the Big Four supermarket chains, who, in turn, between them control 76 per cent of grocery shopping.

Pepsico has the top crisp company Walkers, and Tropicana, as well as Pepsi and other soft drinks and cereals.

Kraft, the American "chocolate, cheese and coffee" combine, has Toblerone and Côte d'Or, Dairylea and Philadelphia, and Kenco and Carte Noire.

Nestlé, the secretive Swiss company behind Nescafé, owns a vast chunk of prime chocolate estate including KitKat, Smarties and After Eight, as well as dozens of other brands such as the bottled waters Perrier and San Pellegrino.

Mars and Cadbury control much of those parts of the confectionery market not owned by Nestlé, while H J Heinz, Unilever and Kellogg's are big in tinned or frozen food or cereals.

Premier Foods has 15 of the top 20 best-selling cake brands; three of the others are owned by United Biscuits. All of the top 15 washing powders are owned by Unilever or Procter & Gamble. (But let's stick to what we can digest.)

So it's hardly surprising, then, that multinationals with the money and the inclination are swallowing up rapidly expanding ethical or specialist brands.

"They all do it for similar reasons – they see the growth at the niche end of markets," says Tim Lang, professor of food policy at City University. "They have seen that there are big areas with big social backing."

Ethical retailing, he points out, amounts to the lucrative emergence of a "values for money" culture rather than a "value for money" one.

reen & Black's embodies this caring corporate culture. Founded in 1991 by Craig Sams and his wife Jo Fairley, the business set out to sell gourmet chocolate: organic (green) and high-cocoa (black). After they'd slogged away for years, the brand became a hit with discerning chocoholics. By 2005, though, Sams felt the business needed a sugar daddy to fund its expansion and help it compete with an emerging threat from organic rivals owned by Hershey and Mars' Seeds of Change. Cadbury, which had taken a 5-per-cent stake in Green & Black's in 2002 with an option to buy the rest in 2005, promised to run Green & Black's as a stand-alone operation.

Announcing the sale, Cadbury MD Todd Stitzer said the businesses shared "a passion for quality products and ethical values" although at the time Cadbury did not have a single organic or Fairtrade product. Buying Green & Black's gave it immediate ownership of the market leader in organic chocolate.

Cadbury acts like a management consultancy to its new subsidiary, supplying technical and legal advice, such as how to set up a factory in Canada or break into Japan. After being in debt for 30 years, Sams says the sale was good for him – and for Green & Black's.

Cadbury has built fermentation facilities in the Dominican Republic to allow growers to earn more from their beans and has challenged the level of pesticide use in Ghana. Green & Black's itself is also vastly bigger. "Green & Black's is generating more benefits in a month than it was in two years when we owned it," he says.

hether ethical brands become less ethical simply by virtue of being taken over is debatable. Ethical Consumer, the Manchester-based magazine, takes into account the standing of the parent company when assessing the behaviour of its adopted subsidiary. Post-takeover, Ben & Jerry's "Ethiscore" rating slipped from 13 to 1.5 out of 20; P J Smoothies from 12 to 1.5; Pret A Manger from 13 to 7; and Green & Black's from 16 to 9.5. Ethical Consumer says the final destination of the money is important; there's no point buying Fairtrade bananas if the parent company is selling arms to banana republics.

Where the money ends up is different, though, from how companies deal with their acquisitions. Corporations are canny enough to know they cannot change too much of the essence of their acquisition, or they risk wrecking its reputation.

"The trick for multinationals buying niche brands," says Ruth Mortimer, editor of Brand Strategy magazine, "is to achieve a good balance between supporting the smaller business and dominating it. Would Ben & Jerry's lose credibility with consumers as an ethical, trendy brand if it was merged fully into Unilever's ice-cream division? Possibly, which is why the unit is run separately, to protect its brand. As a result, most people on the street probably don't even know that Unilever owns Ben & Jerry's."

Back in 2000, Unilever promised to maintain the company's US manufacturing base, to continue buying milk from the Vermont family farmers who spurn growth hormones, and to make other purchases from Fairtrade suppliers. It also promised to keep funding Ben & Jerry's Foundation for 10 years, by more than the $1.1m donated in 1999, the last year of independence. It has not, however, guaranteed to match the founders' pledge of donating 7.5 per cent of pre-tax profits to good causes.

In terms of the business, Unilever does the boring stuff – sales, distribution, finances and human resources – while Ben & Jerry's develops new flavours and markets them.

Greenfield says that Unilever has kept all its promises. But Ben & Jerry's has to ask permission when it wants to question why 50 per cent of the US Federal discretionary budget goes to the military or why there are 10,000 nuclear bombs. "If the company was independent, it would just go ahead and do it," Greenfield complains.

Dominic Lowe, the Cadbury man who became Green & Black's managing director last year, moving from a £1bn-a-year business to a £40m-a-year one, believes the public is more concerned about the deeds of an ethical company than its ownership.

"Do customers think Green & Black's is independently owned?" he asks. "In the back of people's minds, some of our consumers do know. It's probably like Ben & Jerry's – people know it's part of Unilever. But to me, as long as you keep the product quality unchanged that's what they're concerned about," he says. "Cadbury have never interfered in product quality. They have never said: 'Can you reduce the amount of cocoa solids?' "

ounded by three Cambridge graduates who decided to give up their day jobs, Innocent is one trendy company which has so far spurned the advances of suitors. Director Adam Balon says the trio will keep going it alone for now because they enjoy the buzz of overseeing the smoothie company's rapid expansion.

Innocent's turnover has mushroomed from £400,000 in 1999 to £115m in 2008. As well as refusing to use additives or concentrated juice, it gives 10 per cent of its profits to fund rural projects in countries that grow its fruit. As evidence of its fun approach, artificial grass is laid at the company's Fruit Towers HQ in London's Shepherd's Bush, and employees answer queries from members of the public on a phone shaped like a banana.

While Balon is careful never to say never, he and his fellow directors have not been tempted to sell. "We have had conversations. When first interest is expressed you have a meeting because it's flattering. But then you realise there's no point doing it because it wastes everybody's time," he says.

The founders retain 80 per cent of the business, with a business angel who provided £235,000 of funding having the remaining fifth. They have never given away any more, because they have kept tight control of costs and sales have soared.

By contrast, P J Smoothies' market share has shrunk during its stay in the Pepsico empire, which is now heavily marketing smoothies made by its premium brand, Tropicana.

For entrepreneurs, perhaps, the message is: if you want to stay independent, keep hold of your company and grow organically.

For consumers, the message is: don't put too much faith in the label. It's not always the case, but when a company gets bought, its founding vision can get a little blurred. Food is big business – and ethical food is growing fastest of all.

Pure and Innocent: Truly independent brands

Riverford

What started as an organic-box scheme for 30 families at Buckfastleigh in Devon has turned into a national network delivering to 45,000 homes. There's no packaging: the boxes are re-used. Guy Watson started tilling the family farm in 1985 after working as a management consultant

Yeo Valley

Natural-food pioneers Roger and Mary Mead started Yeo Valley as a conventional yoghurt business in 1974, before branching out into organic yoghurt, butter, cream, desserts and fruit compotes. With sales of £73m, the family-owned business's yoghurt is the fifth best-selling in the UK

Innocent

Founded by Cambridge graduates Richard Reed, Adam Balon and Jon Wright in 1998, Innocent promises to squash only fresh fruit – never concentrate – into its smoothies. Despite the hippie shtick, sales are rising rapidly, up 60 per cent last year to £131m

Kelly's of Cornwall

The Kelly family have been making ice-cream ever since their Italian ancestors arrived in St Austell in the 19th century. Flavours like honeycomb swirl are made in Bodmin using Cornish milk and clotted cream and are sold in Sainsbury's, Safeway and Iceland. Sales jumped £6m last year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks