Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A grey winter morning in Kyoto and I – along with several hundred writers, chefs, and nutrition experts from around the world – sit in a conference hall listening to the Michelin-starred French chef Alain Ducasse sing the praises of Japanese food.

“The strict selection of ingredients and the sense of the four seasons are reflected [in Japanese cooking]. Longstanding experience is necessary – but we need to know and learn the basics of washoku,” says Ducasse.

His enthusiasm isn’t surprising considering that just over a year ago, Japan’s washoku became the second cuisine, after French, to be given heritage status by UNESCO (The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). To celebrate, the country’s Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries organised the three-day long Washoku-do, The World Japanese Cuisine Show.

The French chef’s presence is indicative of a growing awareness of the intricacies of Japanese food at its best. It’s a trend the Japanese government is keen to encourage.

Though there are between 55-60,000 Japanese restaurants in the world, only 10% of them actually have a Japanese chef working there. Organisers of the conference want chefs outside of Japan to customise washoku with authentic methods and ingredients local to their area - but also ensure the world sees that there is more to Japanese cuisine than sushi.

The Mayor of Kyoto, Daisaku Kadokawa, tells us about the training programme he introduced last year. He hopes to encourage chefs from other nations to come to Japan to gain hands-on experience with chefs, which they then can bring back to kitchens in all corners of the world.

There is also a competition, the Washoku World Challenge. Set up for non-Japanese chefs from outside the country, the 10 finalists – hailing from Italy to Thailand – have been selected to visit Kyoto to prepare their dishes for the panel of judges. Again, this is all in the hope that their skills would be cultivated and shared on their return, thus promoting authentic Japanese cuisine.

Though there are several popular Japanese chains in the UK - including Japanese fusion restaurant Wagamama, founded by legendary restaurateur Alan Yau and now has more than 100 outlets in the UK - none of these chains were founded by Japanese chefs.

The most popular Japanese cuisine in the UK is sushi, and the industry is now worth £56 million annually. But the style can be different from what one would see in Japan. The California Roll, a classic sushi dish seen in the West, was invented in America, where sushi tends to have more ingredients (such as cream cheese or avocado) than traditional Japanese sushi, which should allow the flavours of the basic ingredients to shine through without too much seasoning. The type of knife used to create the dish is credited with bringing out the right flavours and stop the flesh of the fish bruising, so carefully learned cutting techniques are principal.

In fact, there is a growing awareness of washoku. British chefs such as Heston Blumenthal and Sat Bains have spoken about how they adopted methods seen in traditional Japanese cuisine. The UK’s first Japanese cooking school, Sozai, also opened in 2013, just before Keiichi Hayashi, the Japanese Ambassador to Britain, declared 2014 "the year of washoku".

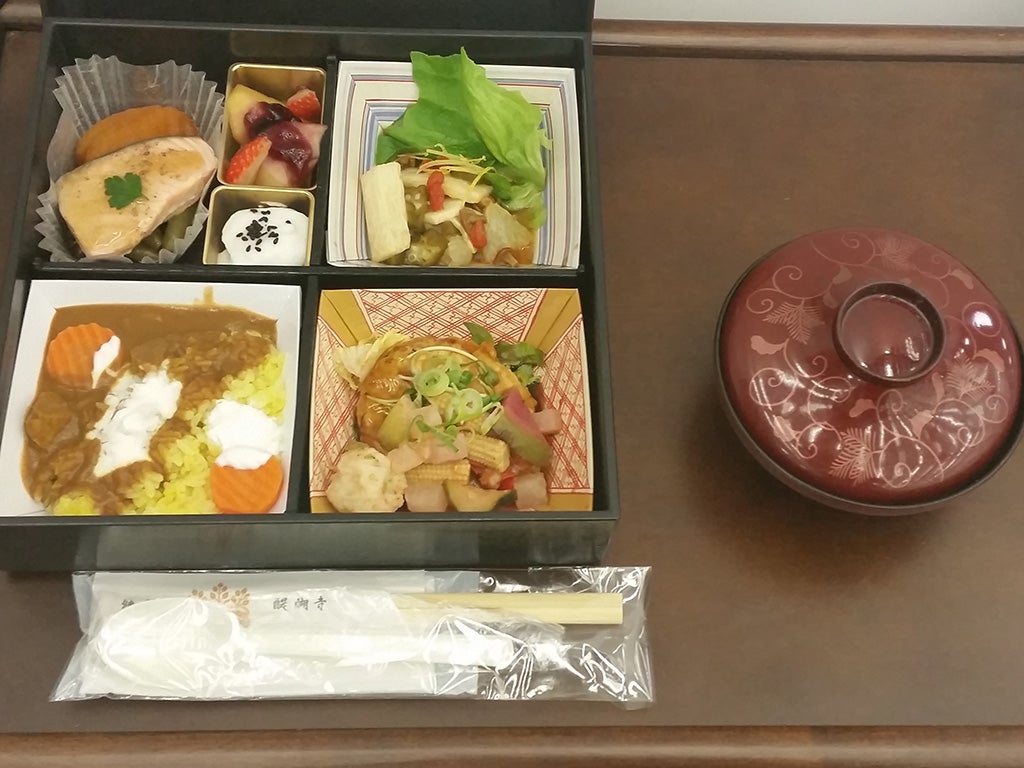

We’ve also seen growth in popularity for other Japanese cooking styles such as Yakitori (grilled chicken skewers), Tempura (deep friend seafood and vegetables), and more recently Kaiseki (multicourse meal for special occasions). Ramen noodles have also become widespread. But the dish taking centre stage at The World Japanese Cuisine Show is Bento, Japan’s famously beautiful lunch box meal. Typically divided into four compartments, it contains rice, sashimi, namasu (pickled fish and vegetables), and a simmered or grilled dish or a salad.

Originally a Chinese dish which moved to Kyoto in the 1300s, Bento is becoming popular in France. While sushi is a lunchtime staple in the UK, with various chains and supermarkets showing how the dish has truly taken on the sandwich, Bento boxes are extremely popular in Japan. And it’s easy to see the appeal: a fresh, colourful, low-calorie, but generously portioned meal.

During my time at the conference, Kiyomi Mikuni, one of Tokyo’s most respected chefs, takes us through the ingredients of the Bento box. It takes the amount of protein, fat and carbohydrate into consideration, as a good nutritional balance is one significant characteristic of washoku, as well as the aim to appeal to all the senses. (A good PFC balance is considered to be 15% Protein, 25% Fat and 60% carbohydrates).

The Bento we are served includes Ampo-Gaki (semi-dried persimmon), which is a local speciality of Fukushima. Ducasse believes that misguided scepticism following the Fukushima Daiichi disaster of 2011, where the world’s worst nuclear meltdown since Chernobyl took place following a tsunami, is a barrier for some to enjoy Japanese food: ‘People think the food isn’t safe,’ he says, ‘it is, and this has to be explained.’

It’s impossible not to be impressed with the aesthetics and taste of the Bento. Even better, we’re told that it’s only 590 calories – surprising for a meal so filling. The awareness of calorific content is unsurprising, however, as health is a top priority in Japan. The Specific Health Checkup, coined the ‘metabo (overweight) law’ was introduced in 2008, which saw local governments and employers monitor the waistlines of people between the ages of 40 to 74 every year: men’s waistlines must not exceed 85cm, and women’s 90cm. If they do, they will be given health guidance, such as counselling, monitoring and support. Only about 3.5% of the population is classified as obese in Japan, compared to around 64% of adults being classed as being overweight or obese in the UK.

As well as the health benefits of washoku, beautiful presentation is key to traditional Japanese cooking. Before the conference I meet Fujita Takako, specialist in Japanese cuisine and owner of a Japanese cooking school in Tokyo. She describes the effort which goes into cooking: “Each dish has elaborate care. You can enjoy the sight of the dishes so you feel satisfied even before you’re full.” Japanese tableware is traditionally passed through generations, so an eclectic and intricately patterned range of beautiful crockery which reflects the seasons is featured in every meal. As our dishes are served in a traditional zashiki setting, Takako also compliments Jamie Oliver’s campaign to make school dinners in the UK healthier, a sentiment reiterated when I later spoke to celebrity chef Harumi Kurihara (who is often compared to Martha Stewart or Nigella Lawson), who again brings up Oliver’s campaign. As the most recognised female chef in Japan, it is clear from speaking to her that health and nutrition is also hugely important in her cooking.

As our time at the conference draws to a close, judge and chef Yoshihiro Takahashi says ‘washoku is a matter of spirituality’ and praises the elegance of the cuisine. Ducasse also said the key aspects of washoku are both the locally-sourced ingredients, and ‘the harmonious Zen technique of preparation.’ Several beautifully presented Bento boxes later, and a peek into the spotless, calm and organised environment where washoku is traditionally prepared, it’s easy to see the appeal of Bento. These delicious, low-calorie meals might just be able to give sushi a run for its lunch money.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments