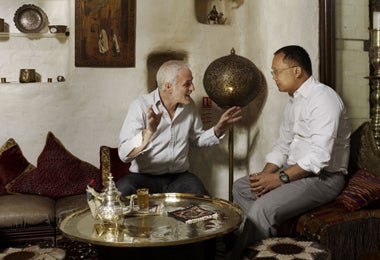

Spicing things up: Mourad Mazouz meets Alan Yau

Why are Britons so boorish about ethnic food? The owner of the celebrated North African eatery Momo chews over the problem with the founder of Wagamama

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mourad Mazouz's Momo, which he describes as his 'little piece of North Africa in the West End of London', celebrated its tenth birthday this year. In 2003, he opened Sketch in Central London, with the famed French chef Pierre Gagnaire.

Alan Yau made his name by creating the Japanese chain Wagamama, which he sold in 1998, going on to open funky fine-dining Chinese restaurants Hakkasan and Yauatcha, both of which have gained Michelin stars.

Independent on Sunday: Why do you think the current focus of restaurants falls more often on chefs than restaurateurs?

AY: When people talk about fine dining today they talk about cuisine, when they talk about cuisine they have to relate that to chefs, so I think from that point of view it's inevitable that the personality of the chef has come to the forefront. I think, though, that to create a really good project it needs both sides to be working properly and sometimes it is the chef who is stronger and sometimes it is the restaurateur.

MM: Thirty or 40 years ago, at least in France, you had the restaurateur that had the money and he was the one that owned the restaurant and the chef was just sweating in the kitchen and yelling. The restaurateur was like the chef's conductor and today I believe that good restaurateurs are still conductors and the chef is the most important musician. The chefs that have become restaurateurs themselves, such as Marco Pierre White and Gordon Ramsay, have two things: personality and luck. Maybe what Alan is doing is more magical because he's not a chef, he's a restaurateur.

AY: I think restaurants that are set up by restaurateurs work very differently to those created by superstar chefs; restaurants in which the chef becomes the conductor as well as the orchestra. Chef-led restaurants typically have a traditional maître d' looking after the front of house and, to me, that style of restaurant is often not as complete as one overseen by a restaurateur. The food might be fantastic but I think they sometimes lack a little bit of soul, they lack energy. '

MM: Restaurateurs are not in the kitchen and so perhaps it's because we have a better view of the whole restaurant.

IOS: What do you look for in a chef?

AY: For me, working with a chef always needs to be about collaboration, because I have strong views on menu strategy and the direction of the food in relationship to my project. I almost act like a hotel-style executive chef in the sense that I want to have the final say with the menu. That's important to me because the whole thing needs to come together in a collective sense and I cannot have a chef with a very strong personality, doing whatever he wants and not caring about what the concept is about. Not only do I need someone who can cook, I also need somebody who's willing to work together and adhere to a certain direction.

MM: For me it's really about finding someone I can get along with and be able to talk to. Also, this might sound a little bit strange but – particularly in terms of North African food – I'd rather have someone who is consistent and cooking at a B+ level as opposed to someone who can sometimes cook A+ but is inconsistent. It's really about getting along, though, not screaming at each other and respecting each other.

IOS: How important is the authenticity of the food you are serving in your restaurants?

MM: Authenticity means nothing to me. I don't know what authenticity means. In Morocco, for example, 30 years ago in Fez they were not eating fish because there were no refrigerated trucks delivering it. Now they have fish and they're serving dishes with fish, does that mean they are not authentic anymore? Authentic is what we live today. Me, I don't have belly dancers – North Africa never had belly dancers and it was never in our culture – and I don't have a man with a big sword standing at the entrance. Momo is not gimmicky, Hakkasan is not gimmicky, it's a real Chinese restaurant but put in a modern environment and done in a modern way. Momo is modern too, in its way – although we do have two palm trees outside – and is the result of the same sort of thinking. We're doing restaurants in 2007 for Londoners. I hope that's authentic because we are both real men.

AY: I do like to keep a level of credibility in terms of thinking about what is Chinese-ness. A restaurant situated in London is going to be very different to a restaurant situated in New York, Hong Kong or anywhere else for several reasons. One, is the availability of the produce and the ingredients. I think that in itself determines a lot of what you can produce in terms of whether something is traditional, authentic or a real London taste. The second thing is – and a lot of Hong Kong customers complain about Hakkasan in relation to this – they say that the taste of Hakkasan for Cantonese food is quite heavy and I have to tell them that it's not heavy but a lot of the menu is strong.

MM: When you say "strong", do you mean strong in taste?

AY: Yes, strong in taste and I'll tell you why...

MM: Because the palate of people in London is not ready yet for something more subtle?

AY: Exactly. The problem is we can't do anything about it, the customers drives the menu because we have to put the items that sell well and get rid of the items that don't. So when I open Hakkasan in Istanbul the menu will no doubt be very different.

MM: You always need to adapt to where you are...

AY: Exactly. A Hong Kong Cantonese restaurant is very different because they love their palate to be extremely subtle and with fish they just want it steamed with soy and ginger and spring onion and to keep it very, very light. The palate here is not like that.

MM: When I opened Sketch, my problem was exactly the same. I like the food we were doing in the first six months much better than the food we are doing today, it was subtle, delicate flavours but people didn't like it, because they didn't understand it. So today, we've adapted it into something that has a stronger taste, it's the same dishes, we've just added a little bit more of everything. This is normal, we need to follow what people want, we are not teachers and we are not educators. I think the beauty of a city like London for me is that people start to understand very quickly. Today, you can do dishes much more delicately and subtle than you could 10 years ago.

IOS: Why do you think the public perception is often that restaurants are too expensive?

MM: Why is it that ethnic restaurants need to be cheap – around £15 to £20 – and if they're more, they are considered expensive? When you take expensive ingredients, when you have a big team in the kitchen and pay a big rent in the middle of London you're the same as any other restaurant that does things well.

AY: I think that people tend to think that ethnic food, especially Chinese and Indian food, should be cheap. They don't see that kind of cuisine as being served at a fine- quality level. That, culturally, has always been the case – and particularly with Chinese food because of the early proliferation of Chinese restaurants in Britain at a very bad level: the greasiness, the MSG and everything else has tainted people's attitude. My point about ethnic food is that I think ethnic food should be more expensive at a fine-dining level than, say, French or Italian food. To do it at that level we have to import everything and it's harder for us than the Europeans, because to do it properly, we have to buy the best and ship it from the other side of the world.

MM: It makes things harder and there's always more drama, because you spend a lot of time worrying if something is going to arrive. To do ethnic food well costs a fortune.

IOS: Do you think British restaurant critics as a whole know enough about ethnic food to review it properly?

AY: I don't think it matters, food critics do their job and it doesn't really matter to me if they know a certain cuisine because I hope that they simply get across how well they eat. Maybe it's even good that they don't know the cuisine that well, because what is more important is that good taste is universal. For a food critic, it's not how well they know a culture or a cuisine but whether or not they have taste.

MM: At the end of the day, critics are important but who cares? A restaurant is a restaurant. If you do your job well, if you take care of your cuisine, if have good service, if you have nice lighting, if the music is right, if the ambience is right and if you have luck, it's not going to matter whether the critics come or not because you're talking to people. Long term, it's your food, your place and your team that talk. *

Alan Yau's new Japanese restaurant, Sake No Hana, opens at 23 St James's Street, London SW1, tel: 020 7925 8988 at the end of this month. Sketch, 9 Conduit Street, London W1, 0870 777 4488, www.sketch.uk.com. Momo, 25 Heddon Street, London W1, tel: 020 7434 4040, www.momoresto.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments