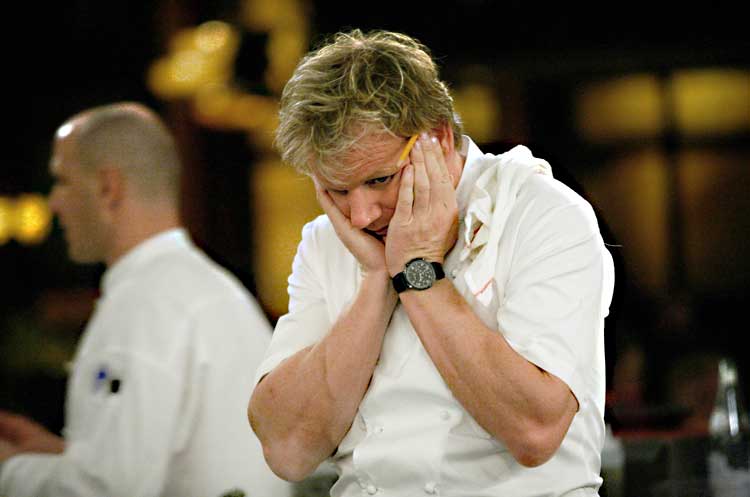

Has Gordon Ramsay bitten off more than he can chew?

He's no stranger to controversy – but now Britain's most famous chef has opened a can of worms by demanding chefs should only cook with seasonal vegetables. Martin Hickman reports

As one of Britain's fieriest, loudest-mouthed celebrities, Gordon Ramsay has never lacked targets. Over the years, his machine-gun rants have been trained on vegetarians, female chefs, Scottish chefs, rival chefs, restaurant critics, and almost everyone he has ever worked with.

Yesterday, it was the turn of an inanimate object: unseasonal food. Britain's most-decorated chef – he has been awarded 12 Michelin stars – demanded the Government outlaw all out-of-season food from every restaurant in Britain.

By making his comments, the chef, author and television presenter was laying down a marker of his personal food philosophy. But he also risked accusations of hypocrisy because he fails quite brazenly to practise what he preaches in his own restaurants, which serve food from thousands of miles away.

Making a call for legislation on Radio 5 Live, Ramsay said: "There should be stringent laws – licensing laws - to make sure produce is only used in season.

"The quicker we get legislation pushed through the Houses of Parliament, the more unique this country will become in terms of its sourcing and level of inspiration. Chefs should be fined if they haven't got ingredients in season on the menu."

Ramsay's remarks place him slap bang in the middle of one of the hottest debates raging in universities, think-tanks, supermarkets and kitchens across the UK: How much British food should we eat?

At a time of rising climate change, increased droughts and rising oil prices, gastronomic thinkers wonder whether we should be growing almost everything we need rather than flying it in from places as far away as Peru. Others believe we have a moral obligation not to pull up the ladder of development to poor farmers in Africa and elsewhere.

Whoever is right, environmentalists are undoubtedly gravely concerned that transporting food around the world is causing vast and unsustainable pollution. Despite a government commitment to lower the impact of food miles by a fifth by 2012, they keep rising because of our fondness for unseasonal and exotic food and the growth of out-of-town supermarkets.

They soared by 31 per cent in 2005, the last figures released by the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. The social, environmental and economic bill is put at £9bn every year.

Using more local food makes sense financially, environmentally and nutritionally. But can it ever really make sense to use only local ingredients?

The £70bn-a-year British food business voiced support for Ramsay yesterday, backing his call for people to rediscover the joy of seasonal food but even it felt that he had over-egged his case.

The National Farmers' Union sympathised with the chef but said there was already too much legislation on food.

Raymond Blanc, who runs Le Manoir aux Quat Saisons in Oxfordshire and who has been on the receiving end of Ramsay's insults in the past, said: "I am glad M. Gordon Ramsay is taking an interest, albeit belatedly of course, that our gastronomy has become separated from the real issues.

"It's a very nice idea [the fines] but you have to face the difficulty, which is the climate. We have a short season for growing, from May to October. We are a net importer of food, so there are real issues to think about."

The Frenchman – who serves up fruit and vegetables grown in Le Manoir's grounds – added: "It's wonderful at last that we are truly reconnecting with the most fundamental values but it's going to take a long time because you cannot, in a day, transform 40 years of ignorance into knowledge."

International aid agencies were less sure. "I'm sure the millions of farmers in east Africa who rely on exporting their goods to scrape a living would see Gordon Ramsay's assertions as a recipe for disaster," thundered Oxfam's head of research, Duncan Green.

"He, like all of us, wants to tackle climate change but it is vital we ensure that poor people who are already hit hardest by climate change are not made to suffer even further. There are better ways to tackle climate change.

"If everyone switched one 100 watt light bulb for a low-energy one, UK emissions could be cut by almost five times as much as would be saved by not purchasing fresh fruit and vegetables from Africa."

Even Ramsay's own restaurants, which include the newly opened Plane Food at Heathrow airport's Terminal 5, would fall foul of his suggestion.

A statement from his business empire, Gordon Ramsay Holdings, explained that it recognised the importance of sourcing local seasonal ingredients, adding: "Nevertheless, the overriding concern for all our chefs is that they only use the highest quality produce and, therefore, in some cases, they source ingredients from further afield."

So if Ramsay does not use only local ingredients, why did he make his comments?

The former footballer gave his pre-recorded interview to the BBC on the understanding it would be broadcast yesterday, shortly before the launch on Tuesday of a new series of his Channel 4 show, The F-Word.

Like Richard Branson, Ramsay has been powered in his career by the oxygen of publicity. He is an accomplished stirrer.

Clare Smyth, his new head chef at his signature three-Michelin-star restaurant in Chelsea, last month snorted at a suggestion that Ramsay wanted an all-women team at Restaurant Gordon Ramsay (while learning a trick from her master by describing another of his female protégées, Angela Hartnett, as a "one-star" chef). "He's such a naughty boy," she laughed. "He'll say anything to get a controversy started."

The 41-year-old chef may also feel the need to refresh his image after a decade at the top of the business. Some of his mononym celebrity rivals are known for campaigning; Hugh [Fearnley-Whittingstall] does factory-farmed chickens while Jamie [Oliver] does school dinners, home nutrition and factory-farmed chickens.

Gordon has just done cooking, in his restaurants and at other people's. With his international empire attracting criticism that he has become too corporate, his rivals getting ever deeper into the politics of food – and a new show to promote, perhaps it was no surprise that Ramsay's views were so strident.

Then again, he has regularly vaunted local produce on his Kitchen Nightmares show, in which he turns round failing restaurants. His advice almost invariably involves ditching a pretentious menu and serving regional fare.

His motivation for having local fruit and vegetables, he told the BBC, was to invigorate cooking and excite diners. "When we haven't got it, take it off the menu," he explained, protesting that he did not wish to eat asparagus in December or Kenyan strawberries in March.

Peter Melchett, policy director at the Soil Association, which wants to limit the air-freighting of organic food to the UK, said: "I would agree with the huge importance of getting back to eating a much more seasonal diet. I don't agree that fining chefs is the most constructive way of doing that.

"I think it would be much better if the public started to shun restaurants that don't have seasonal ingredients on the menu."

But the odd tomato or punnet of strawberries in winter was still acceptable, said the veteran environmentalist. "Trying to be absolutist is both unreasonable and overly optimistic," he added.

What the chefs say

Paul Merrett, FORMER HEAD CHEF AT THE GREENHOUSE AND THE FARM

I was born in Tanzania so I have a huge amount of sympathy with the argument that when people in the West buy locally they might be hurting people in the Third World who depend on our purchases. But the "foodie" in me says we must at least get back to a seasonal mentality with our food. Not only can it be better for the environment in terms of food miles, but the taste is so much better. I think Gordon has taken it to an extreme, but I spend a lot of time in fine dining restaurants and I can tell you that they're the biggest culprits of all.

Brian Turner, head chef at the Millennium Hotel, London

Let's use common sense: seasonal food and local produce, when of the appropriate quality, should always be preferred. We want to do as much for the environment as possible, and to ensure we have excellent tasting food. This means choosing intelligently, and from different places at different times: at the moment Spanish strawberries are in season, but when British strawberries are we should use them. In terms of buying produce from poorer parts of the world, the cynic in me is unsure the poorest people actually see any of our money in any case.

Greg Wallace, presenter of Masterchef and founder, Home Grown Direct

I believe strongly in eating seasonal produce because it is cheaper and better. Don't buy strawberries from Venezuela. Wait for them to come into season in Britain, and source them here. Do buy mangoes from Venezuela, because they're fantastic. I think we should support British farmers and promote our own food culture where possible. I think if we moved to a model where every country specialised more, we'd all be happier. I love a good banana: we can't grow them here, so we should import them. That's good economics.

Mark Hix, The owner of Hix Oyster and Fish House, and Hix Oyster and Chop House, london

So many restaurants in London aren't even vaguely aware of the seasons. The whole point of cooking in season is that it gives the customer something to look forward to: if things are available all year round, they lose their novelty. Seasonal cooking makes planning a menu much, much easier; it allows menus to evolve and to return cyclically. There are some specialist products that are best produced elsewhere – coffee, for example, or some fruits – and those should be freighted over.

Jun Tanaka, Executive Chef, Pearl Restaurant, London

Seasonal produce is incredibly important. To a large extent it dictates what goes on the menu. Produce that is in season is full of flavour and good value. I can see the merit of having produce available all year: it gives people choice. Supermarkets have blurred the lines between the seasons. I've got no problem with cherry-picking the best imports. But supporting local farmers is important too, and as a chef my primary aim is to get the best quality food for my customers. More often than not, that means local produce, in season.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks