Why binning your leftovers is a moral issue: just ask the Tudors

Legal requirements to donate leftovers to the poor, punishments for those who don’t and enforced childhood lessons about the importance of not wasting food. No, this is not 2050. This is Tudor England. In an extract from her book ‘Leftovers’, Eleanor Barnett shows us what the past can teach us about the future of food waste

Like today, wasting food in Tudor and Stuart England was an issue deeply laden with moral implications. During the 16th-century Reformation, when England transitioned from a Catholic country under the pope to a Protestant state under the crown, a religious mindset underlined all aspects of daily life.

While food waste today is presented in secular terms as an affront to environmental sustainability, writers of the early modern period saw food as a gift from God: to waste it was to abuse and reject God’s heavenly benevolence.

People believed food physically sustained earthly life by literally replenishing the flesh that was used up day-to-day. And it was food that Christ had chosen to represent his body and blood in the sacrament of the Eucharist.

It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that in his Treatise of Faith published in 1631, the Puritan preacher John Ball described the daily rituals of dinnertime as a spiritual experience.

The food on the plate, “is not ours”, he argued, “but the Lord’s, all the provision are gifts of his mercie in Iesus Christ”. Any food left over must not be lost, but we “reserueth it for good vse”.

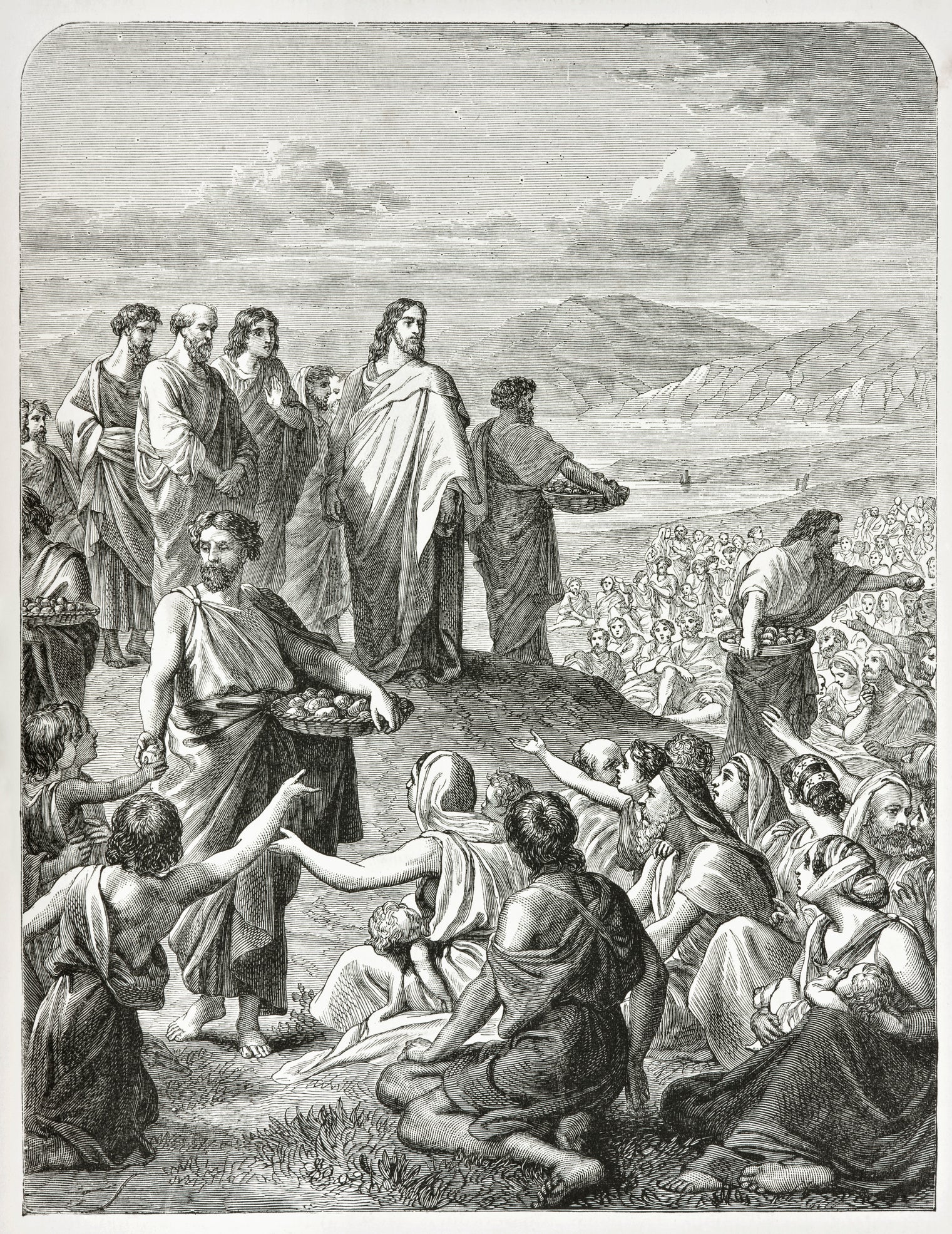

This was a lesson repeatedly taught through the parable on the Feeding of the Five Thousand. Many of us are still familiar with the story: a mass of people gathered around Jesus when he went to mourn the loss of John the Baptist, but the group’s provisions were meagre, comprising only five loaves and two fish.

After giving thanks, Jesus broke the bread and fish into pieces, and by a miracle, there was suddenly enough food to satisfy the entire 5,000-strong crowd.

Importantly, as recounted in numerous sermons of the early modern period, Jesus then told the disciples to “gather up the ‘broken meates’”, referring to the leftover food, “so that nothynge be lost”.

In his Of Domesticall Duties (1622), the clergyman William Gouge used this story to warn servants of their duty to stop food from lying “in corners moulding, or to be cast up and downe for dogs and cats”.

Likewise, Robert Cleaver, another Puritan-leaning minister, lectured servants not to waste leftover food, not only because it was “a hinderance to their master’s profit”, but because it was “a great offence to God”.

In 1640 the Puritan writer Ezekias Woodward admonished parents of children in the habit of “spoyling much more than they eat”.

Children were known (then as now) to leave a fair amount of their food. Woodward warned that in one family accustomed to such wasteful table manners a “sicknesse came, and tooke away the parents” as a divine punishment which resulted in the parents’ friends having to take on the guardianship of the orphaned children.

Children would surely be shocked into less wasteful eating habits, he reasoned, if they were aware that in the time of King Edward II, in 1315, the kingdom suffered such hunger that people resorted to eating horse flesh… and even their own children.

So what was a good Christian meant to do with leftovers if they were fortunate enough to have food to spare? According to the Puritan theologian John Downame, anything that remained after a meal should be offered to the poor.

In rhymes, Thomas Tusser’s Five Hundreth Pointes of Good Husbandrie, one of the biggest-selling books of poetry in the Elizabethan era, repeated this message. Good household management could help the poor: “Ill husbandrye eatith/ him selfe out a doore/ good husbandrye meatith, him selfe & the poorer.”

Other household management books were more specific. Gervase Markham’s The English Huswife of 1615, the most popular cookery book of the era, directed the reader that “the best vse of buttermilke”, the liquid left over from churning butter, was for the housewife “charitably to bestow it on poore Neighbors”. Whey, the leftover liquid from the cheesemaking process, should also be given to the poor to drink as they toiled in the fields in the hot summer, or otherwise fed to the pigs.

Of course, during the many years of bad harvests when malnourishment was a real possibility, the charitable giving of leftovers was even more imperative, and was encouraged with urgency from the pulpit.

At the gates of the palace, then, two food worlds collided: the court, with its opulent piles of meats, pies, soups, fish, jellies and sweets; and the desperate, hungry poor

In that barren year of 1596, clergymen instructed their parishioners to skip supper on Wednesday, Friday and fast day evenings, to avoid “nedeless waste and riotous consumption”, and to donate the food that was saved to those in need.

In grand households, the distribution of leftovers to the poor had long been a more organised affair. An ordinance of 1526 for the reform of daily life in King Henry VIII’s court required food scraps and dregs of ale to be distributed to those in poverty.

This mandate was taken seriously. It was the duty of the officers of the almonry, “upon paine of imprisonment”, to make sure no food was wasted.

The almonry was to place two vessels in the scullery – one for solids, one for liquids – where anyone in court would send their leftovers. Those who disobeyed would be punished with the loss of their allowance, lodging and the right to eat and drink at court, a harsh punishment indeed for those who sought the fame and fortune of being a courtier.

It was the duty of the under almoner to oversee the distribution of the scraps collected to the poor who waited eagerly at the gates.

At the gates of the palace, then, two food worlds collided: the court, with its opulent piles of meats, pies, soups, fish, jellies and sweets; and the desperate, hungry poor.

Attitudes towards charitable giving were changing in the Elizabethan period. As poverty increased, the state intervened to enforce parish support for those who were unable to work on account of illness or old age.

Relief for the poor was increasingly bureaucratic and systematised by the state, which levied taxes to support people who struggled to afford sustenance, and funded almshouses to house them.

Unlike in the Catholic medieval period, when wealthy individuals made charitable offerings of food that were, in theory, available to all those in poverty, by the later 16th century the poor were often seen as “undeserving” of such handouts.

In the household of Henry Stanley, the Earl of Derby, “vagrant persons or maisterles men” were excluded from hospitality in 1587.

In the early Tudor period, manor houses regularly fed strangers in their great halls. This was especially true in the Christmas period, when Twelfth Night feasts took place. Yet, by the Jacobean era, the lord and lady of the manor increasingly withdrew to private quarters to eat.

Nevertheless, the Earl of Derby’s household continued in the 1580s to distribute its discarded food and beer as alms to the people in need whom it deemed worthy, and the religious tradition of offering leftovers at the gates of grand houses certainly survived into the late 16th century.

When William Harrison chronicled the food and drink of the English in 1577, he noted that when the nobility had “taken what it pleaseth them” from the table, “the rest is reserved, and afterwards sent down to their serving men and waiters”, with anything left “being bestowed upon the poor which lie ready at their gates”.

‘Leftovers’ by Eleanor Barnett is published by Head of Zeus

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks